Facing Trump’s asylum limits, refugees from as far as Africa languish in a Mexican camp

A group of roughly 100 Haitians, Africans and South Americans cross the Rio Grande, just shallow enough for adults to wade despite an overnight storm.

As they wait on the muddy bank near Del Rio, Texas, to surrender themselves to the Border Patrol, the voices of children in the group carry across the river to the Mexican side.

There, in the city of Ciudad Acuña, hundreds of migrants have formed an impromptu refugee camp in an ecological park bound on one side by the river. Just outside the park, the official port of entry to the United States sits at the end of a short bridge.

They’ve crossed thousands of miles by foot, boat and bus to seek asylum in the U.S., only to find themselves stalled in a purgatory of soggy tents and overflowing bathrooms. Now, they face an uncertain wait prolonged by Trump administration policy.

The temptation to make the risky and illegal river crossing mounts daily.

“If you see people jumping over the river, it is because they are tired of staying here,” said one resident of the camp, Luis, who declined to give his last name out of fear for the safety of his family back home.

Home for him would be the West African nation of Cameroon, where Luis was vice principal of a school until he fled last fall. He escaped a widening conflict between the country’s English-speaking minority and its Francophone-majority government, which receives security assistance from the U.S.

He was jailed and tortured before escaping to neighboring Nigeria, Luis said. After a trek across three continents, he landed here, where he has waited for six weeks to present himself to U.S. officials at the Del Rio port of entry.

He hopes to join a sister in Ohio.

“At times, it is really disheartening,” he said, “so it is difficult to wait.”

Headlines from the border in recent months have focused on a surge of Central American families fleeing violence and poverty who have overwhelmed a U.S. immigration system geared primarily to handle single adults.

But reporting along the roughly 400 miles of the Rio Grande from Del Rio to Juarez, Mexico, shows a more complex picture of the kaleidoscope of people seeking shelter in the U.S. — and the sometimes perverse incentives that encourage them to cross illegally.

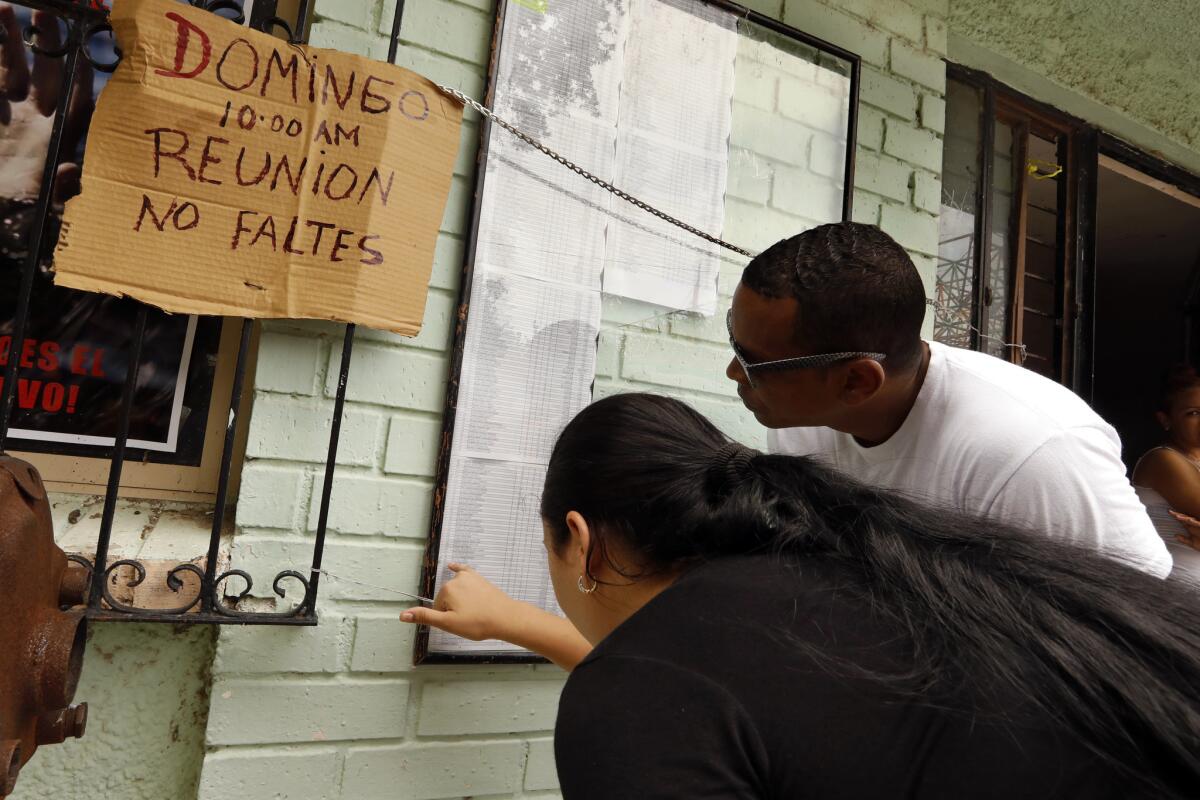

Under a Trump administration policy called metering, U.S. authorities allow only a handful of asylum seekers, if any, to pass through ports of entry each day. Luis had gone initially to Matamoros, across from Brownsville, Texas. But finding himself number 1,913 on the informal wait list there, he followed a Cameroonian friend to Acuña. Now his number is 315.

“Very few people are taken; others are going illegally,” he said. “It is very simple to cross, but we don’t intend to.... We don’t want to violate the laws of the United States.”

In recent days, the wait list here reached 500, although because it is updated inconsistently, the true total was probably closer to 700 — Cubans, Haitians and South Americans, as well as those from the conflict-torn African nations of Angola, Congo and Cameroon.

Some have waited more than six months here and elsewhere to pass through gates like those just outside the camp, cross the international bridge and formally make an asylum claim — as the Trump administration has admonished them to do.

Borderwide, about 15,000 migrants are believed to be waiting. Roughly 15,000 more have been returned to Mexico by U.S. officials under the administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy. They’re required to wait south of the border until their cases wind through American courts — a process that takes two years on average.

U.S. officials say metering is needed to deal with a flood of asylum seekers; opponents have sued, saying the policy violates U.S. law that establishes a legal right to asylum.

The metering policy, begun in Trump’s first year, when he boasted the lowest number of apprehensions at the border in nearly 50 years, has transformed even smaller Mexican border cities like this one into overcrowded, fetid refugee waiting rooms, pushing many toward the river.

The pressure has continued to grow: Community leaders in Acuña recently informed the migrants that officials would soon close the camp. Its inhabitants don’t know where they will go.

In the camp, those who wait are angry with those who cross for drawing unwanted attention from U.S. and Mexican authorities.

In the camp’s two bathrooms, waste oozes out of the floor and sinks. Flies buzz around overflowing trash and unrefrigerated food. Temperatures are now often rising above 100 degrees.

Worst of all, many say, are the mosquitoes.

“Mosquitoes here are the size I have not seen in Africa,” Luis said.

Still, he said, they will wait.

“Those of us who have come from Africa, especially from Cameroon, what we have gone through, I’m sure we will continue to wait here, even if it’s a year,” he said. “It is far better than anything we have seen in our country.”

“In our nation, we slept with corpses.”

‘Treated with the same kindness’

Across the river in Del Rio, Sheriff Joe Frank Martinez navigated a big truck on small roads following the bends of the Rio Grande. He kept watch for migrants crossing in the early morning dark.

“We have a little hidden gem here,” he said of his town.

Del Rio had largely avoided the migration surge until recently, explained Martinez, who has worked in law enforcement there more than 30 years and served as Val Verde Country sheriff since 2007.

With large numbers of migrants suddenly arriving from African countries many of his constituents have never heard of, he believes smugglers are involved.

“This is a sleepy town, and I’ve always said we don’t want to be the weak link in the chain,” he said. “They know it’s easier to come through here.”

Lately, he’s spent significant time combating Facebook rumors seeking to tie migrants, particularly Africans, to alleged crimes in the community. But crime has stayed low, he said. “It’s just fear.”

Border Patrol agents in the Del Rio sector have arrested some 40,000 people already this year, more than double last year’s total. They hail from 50 countries, government statistics show. Some two dozen immigrants have died here.

Immigrants crossing the Rio Grande are just one challenge facing local border agents.

Since early May, U.S. officials have sent migrants to Del Rio from overcrowded detention facilities across the state of Texas. With no place to shelter them, officials release scores into town almost every day. The migrants receive court dates and are left to make their way as best they can to communities where friends, relatives or support groups can help them while they wait.

Del Rio, like Acuña, doesn’t have a migrant shelter, or many transportation options — and the city wants to keep it that way, said Tiffany Zook, secretary of the Val Verde Border Humanitarian Coalition.

“The city probably doesn’t want to take on that financial burden,” she said.

In April, Border Patrol agents warned city officials that they would be releasing migrants in the town whether it was prepared or not, said Zook, whose husband is an emergency medical technician and vessel commander with a Border Patrol river unit. So she and local faith-based groups formed the coalition. The city leased them a building in May but stressed it could not be used to shelter migrants long term.

On one single day in late June, volunteers scrambled to provide food, showers and transportation to San Antonio for roughly 100 migrants dropped off by the Border Patrol. Many families arrived hungry, dirty and sick.

An ambulance was called for an 18-month-old girl, Djinie Desin. Customs and Border Protection officers had taken Djinie and her mother, Juline Previlon, to the hospital after the baby fell sick, said Previlon, who is from Haiti. A bandage on the child’s thigh marked where she’d received an injection. Afterward, they were returned to detention.

A Customs and Border Protection officer who’d just dropped off another group said they were no longer responsible for the pair.

Caring for the migrants is the coalition’s mission, said Zook, her eyes welling up.

“Honestly, if America ever had a crisis, and we all had to flee to Mexico,” she said, “we would hope that we’d be treated with the same kindness.”

Cross-continental journey

Bernard Manuel is perched on an upside-down bucket in the middle of the Acuña camp, holding a small violin.

In Angola, the 26-year-old worked in construction in Luanda, the capital, but loving music, he taught himself to play. A shop owner in Acuña gave him the child-sized instrument, he said.

“I wasn’t looking to buy,” he said, “but he gave it to me.”

Manuel said he was in Luanda when his mother, father and brother were killed in an infamous April 16, 2015, police raid on a dissident sect of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. The sect had thousands of followers in Angola, but the government had declared it illegal.

“The police killed many people,” Manuel said.

Continued religious persecution forced him to flee in January, he said, first to South Africa, then to Ecuador, where he began the trip north.

Growing numbers of Africans who find themselves blocked by tighter refugee policies in Europe and the United States take advantage of loose visa requirements in Brazil and Ecuador to gain a foothold in the Western Hemisphere.

They then use a cross-continental land bridge to the U.S.-Mexico border — typically trekking through Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala to Mexico. They mingle with the much larger, though slower-growing, numbers of Central Americans, as well as Haitians and Cubans.

In 2018, the last year with complete data, Mexican immigration authorities encountered nearly 3,000 African migrants. In the first four months of this year, they already had encountered nearly 2,000, with Cameroon, Congo and Angola the top countries of origin.

Unlike Central Americans, whom the Mexicans can readily turn back, the country has no effective way to return Africans to their homelands. Instead, Mexican authorities typically issue 20-day transit visas. From January through the end of April, Mexican authorities removed just five Africans from the country, official figures show. By comparison, they removed more than 146,100 Central Americans.

Manuel said he spent $4,000 on his six-month journey from West Africa — and that was only until Panama, where he ran out of money. Panamanian officials and other migrants took pity on him and helped him the rest of the way to Mexico.

Since May 18, he’d been waiting in Acuña. He joined the list at No. 234.

He hopes to make his way to a friend in Iowa.

“On the border, there is a lot of corruption,” he said. “People give money to officials to look the other way as many people cross the river … if you have money, you can manipulate the process.”

Later, familiar music rose above the noisy camp — Bernard playing “Amazing Grace.”

‘I want to save my family’

Some 400 miles up the river in Juarez, across from El Paso, Kabuya Mutombo spent hours in the late June sun on his phone, tethered to an electrical strip in the courtyard of the Buen Pastor shelter.

Quietly, the 45-year-old father — who goes by Robert here — was trying to figure out how to get himself and his three children to Acuña.

In May 2016, Kabuya said, government forces entered their village in the Democratic Republic of Congo and opened fire. He grabbed Sara, now 16; Lucas Stefan, 12; and Acasia Maria, 5, and ran for the bush. They’d been on the move since.

“Everyone must run to survive,” Kabuya said.

For days, they ate only what they could find in the brush and took turns carrying the youngest until they made it to Angola. He still doesn’t know what happened to his wife, Marie Dembo Matumbo, who’d been visiting a friend in another village.

“Since the war appeared in my country, we didn’t meet again,” he said. “We are trying to find her.”

He spent a year in Angola struggling to provide for his family until a friend told him that a large group of Congolese was soon setting off for South America.

“We are going to seek asylum, if you take this way,” the friend said. “We are going to USA.”

Kabuya pooled $3,000 for a recommended guide, borrowing from friends and paying upfront. In January, he and his kids flew to Ecuador on fake passports. It was their first plane ride.

“This way, I know it is very difficult, but it was not impossible,” he thought then. “I can do it, because I want to save my family.”

From there, the children braved a crowded, rickety boat to Colombia; the weeklong jungle crossing to Panama; intimidating border checks and thousands of miles — all without complaint, he said. Asked how, he responded that they had already seen war back home.

“They are young, but they know,” he said. “I told them you must believe.”

At Mexico’s southern border, the family waited almost three weeks for papers to continue north. When they stepped off the bus in Juarez, Kabuya was stunned to learn his number: 13,995.

They’d waited a month at Buen Pastor when the three kids suddenly began packing up and saying tearful goodbyes. Kabuya was already at the bus station, said Sara, his eldest, explaining that they were going to meet Congolese friends in Acuña.

They’re still waiting. Mexican authorities didn’t allow the family to board the bus, Kabuya said, because their papers had expired. He tries to encourage his kids, describing to them their final goal: Portland, Maine, where he has friends.

“We are going somewhere, someplace good,” he tells them. “Right now we are suffering. But after tomorrow, we will not suffer again.”

Dream to reach U.S. never dies

One recent night, as slate-gray storm clouds and mosquitoes rolled over the camp, a group of Cameroonian women cooked chicken drumsticks over small fires.

“We have a friend of ours who is Mexican, and we are celebrating his death here like Africans,” Luis explained.

They’d pooled their meager funds to honor the Mexican man, who’d befriended the group on visits to the camp. He was shot and killed in the street. They don’t know why.

Without work permits and with their transit visas long expired, the Cameroonian group and others in the camp depend on occasional donations from local Mexicans and Texans crossing the border. Some tents had been robbed.

But asked how the camp compared with Cameroon, Luis laughed.

“This place is the best I have lived,” he said. “In Cameroon, every day is gunshot. You are hunted.”

He repeated his determination to wait for his number to come up.

“We want to get to the States with clean hands,” he said.

Days later, he crossed the river.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.