Neo-Confederates in Congress resist a rapidly changing world

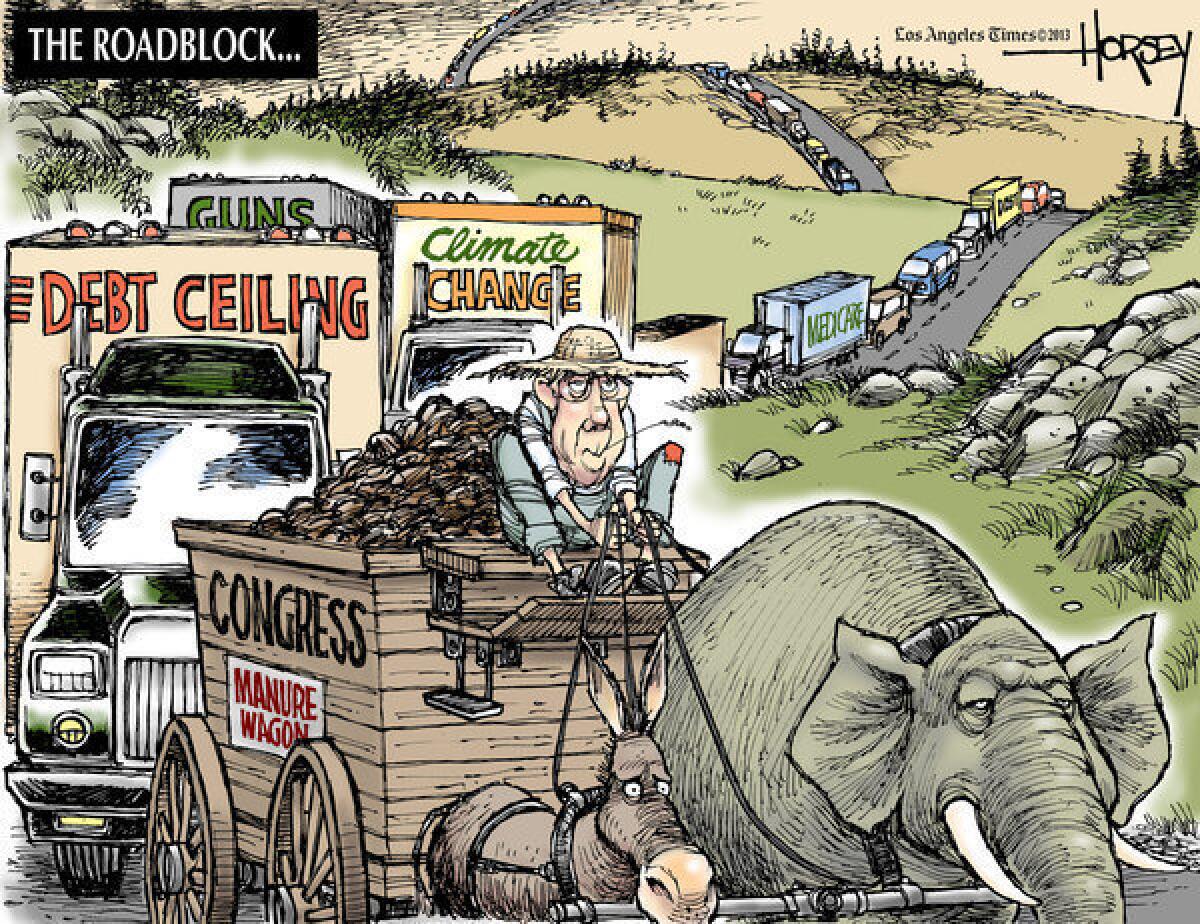

Revolutionary changes are coming at us at supersonic speed, bringing new challenges that are existential and global. Yet our political system seems incapable of adapting to, or even fully acknowledging, those changes. Instead, the system is constricted by ideas and attitudes better suited to the 19th century.

In the current issue of Vanity Fair, Todd Purdum equates the current era with the decades before and after 1500 during which the New World was discovered and explored, trade became a global enterprise, the Reformation broke the religious monopoly of the Roman Catholic Church, the feudal system gave way to nation states and movable type and the printing press created the first form of mass communication.

The introduction to Purdum’s column sums up his thesis: “Not in 500 years has the world seen such revolutionary change as it is now witnessing: the Internet, genetic engineering, mass migration, climate change, worldwide economic dislocation, a new global elite, and more.” Then comes this kicker: “Yet our leaders don’t seem to take any of it seriously.”

Well, a few of our leaders do. But our political system does not, in general, reward politicians who bust up our comfortable myths by acknowledging, as Abraham Lincoln did, that “we must think anew and act anew” in order to save our country. The reactionaries of Lincoln’s day did not see him as a visionary who would lead the country on a more enlightened path. They saw him as a dangerous radical and, to preserve the rotten, wicked, entrenched old system, they drove the country into civil war.

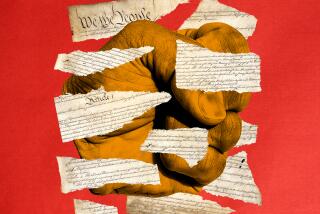

Today, there are quite a few very vocal neo-Confederates who think gun rights, states rights, the protection of white American culture and elimination of “excessive” taxation on the rich are the nation’s preeminent concerns. Their antebellum mindset makes it impossible for them to accept scientific reality -- climate change, evolution, the true age of the planet -- and political reality -- America is becoming a more diverse, tolerant nation that does not share their fear-driven philosophy.

One of our two great political parties has been captured by the neo-Confederates and, because so many of them have been elected to Congress, the political system is gridlocked. Big problems are either ignored -- climate change, deterioration of infrastructure, the toxic greed in the financial system -- or kicked down the road to be fixed another day.

As bad as things are, though, governmental paralysis created by reactionary resistance to change is not unique in our history. For most of the first century of the republic a final resolution to the slavery issue was kicked down the road over and over. Lincoln and the Union army finally forced the necessary realignment.

In the Gilded Age, the political power of the robber barons sustained a system of exploitation until Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressives upset the political balance.

It took the Great Depression to bring low the titans of finance and their toadies in Congress and raise up Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal.

Racial apartheid in the American South was propped up by politicians who gave way only after years of struggle created a new awareness in the country and allowed Lyndon B. Johnson to make racial justice the law of the land.

Change is constant but our political system always lags behind until the force of change is too great to resist. The fact that those who are now clinging to the past have become so rigid, desperate and shrill is a strong indication that a big leap is drawing close. We have not found our Abe or Teddy or FDR or LBJ, as yet. Barack Obama is more a manifestation of a changing America than he is the agent of a revolutionary shift. But when the shift comes, leaders will rise to the moment and history will call them great.

That is a hopeful thought at a dismal moment in our democracy.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.