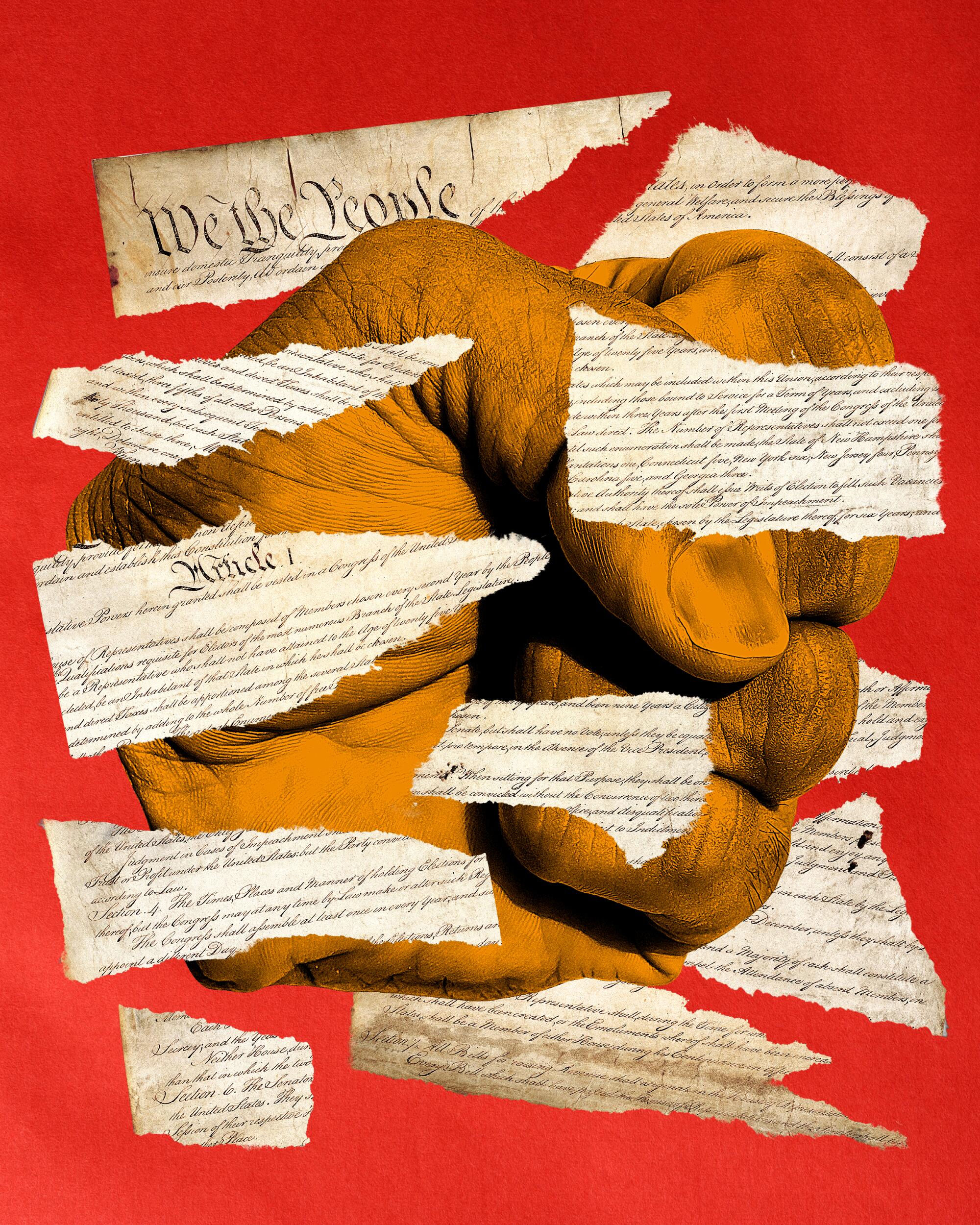

FORMER (AND PERHAPS FUTURE) PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP has been saying some strange things lately.

“I am your retribution,” he told the annual CPAC conference back in March. In a Veterans Day speech, Trump told a New Hampshire audience “We pledge to you that we will root out the communists” and “the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.” In a recent exchange with Fox News host Sean Hannity — after Hannity bent over backwards to get Trump to say he had no plans to be a dictator — Trump said that he only wanted to be a dictator “on the first day” of his new administration. It has been widely reported that Trump and his allies are planning to invoke the Insurrection Act, allowing the president to deploy troops to crush protests.

Since 2015 there has been much debate about whether or not Trump is a “fascist.” That debate is now over. Trump probably does not understand enough history or political theory to realize that he is a fascist. But instinctively he has found his way there. His language of “retribution,” of “vermin,” and of wanting to be a “dictator,” is a precise and highly alarming echo of the rhetoric of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in the early 20th century.

If he is elected president again, there will be no H.R. McMasters, no John Kellys, no Gen. Mark Milleys, restraining him from doing his worst. His administration will be packed with fanatical loyalists.

Americans have not seen a potential chief executive or a potential administration like this before. But other countries have. Historical parallels can help us understand better the kind of politics Trump is proposing, and the kinds of things we can expect to happen.

PERHAPS YOU ARE THINKING: This is a bit hysterical. Americans aren’t going to vote for dictatorship.

Perhaps not. But Germans in the 1930s didn’t think they were voting for a dictatorship, or another world war, or genocide.

One thing the historical record shows us is that fascists get more extreme with time (and we have already seen this with Trump). Anywhere they have come to power, they have done so through an electoral system in which they have had to persuade a significant segment of the voters to support them, usually in alliance with conventional conservatives. For this reason, they play a complicated game with their messaging.

Both Mussolini and Hitler told voters exactly who they really were. When asked by a liberal reporter about his program, Mussolini replied that his program was “to break the bones” of democrats like the reporter. Before he came to power, Hitler liked to say that when he came to power, “heads will roll in the sand.”

When challenged on these words, the fascists typically backtracked — a bit. When a supreme court judge asked Hitler to explain what he meant by “heads will roll in the sand,” Hitler passed it off as metaphorical. He said he would abide by Germany’s constitution and had no plans for a coup d’etat. But like Trump, he couldn’t quite leave it there. “I may assure you,” he said, that when his movement had “won its legal struggle” there would be “retribution,” and “heads [would] also roll.”

When the Nazis needed to win free elections, they talked about other things — things that most voters cared deeply about. The Great Depression had hit Germany harder than any other country so the Nazis talked about “work and bread.” Most Germans felt their country had been victimized by a globalizing economy so Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels wrote that “we want to build a wall around Germany,” and Hitler complained about German companies sending jobs, such as shipbuilding, to China. Most Germans felt humiliated and angered by defeat in World War I, the terms of the peace treaty, and foreign occupation so the Nazis promised national assertion and national honor. In fully free elections in 1932, this messaging attracted just over a third of the electorate — more than any other party, but well short of a majority in Germany’s complicated parliament.

The Nazis made no secret of their antisemitism, even if they spoke about it more in code the closer they got to power. And in the last semi-free German election, in February and March of 1933, their talk about dictatorship was strikingly similar to Trump’s now. The leading Nazis made blunt speeches promising that whatever happened, this would be the last election. “We are not willing to leave the field voluntarily,” Hitler’s interior minister told an election rally. Goebbels told a Berlin audience that Germany’s Communists “should not believe that everything will remain as it is today.”

The talk of dictatorship was meant for the Nazi base. So was talk of what would happen to enemies after the Nazis won. In almost exactly Trump’s words, the Nazis promised they would “exterminate the noxious Communist brood root and branch” just as “one kills off rats or bugs.” The base loved it. But such talk did not frighten away other voters who jumped on the Nazi bandwagon. In March 1933, the Nazis secured 43% of the popular vote.

The Nazis were right about one thing. That was the last free German election at a national level for the next 16 years.

THIS HISTORY HELPS US UNDERSTAND why Trump’s talk of dictatorship and retribution shouldn’t be brushed off as hyperbole. These messages could work because many Americans want a dictatorship. Perhaps even a third of the electorate, just like in Germany in 1933.

The journalist Tim Alberta recently said on the PBS NewsHour that many white Christian evangelicals believe that they “are now losing status in ways that they have never seen before ... There is a sense of impending doom ... that the government is coming for them, that Christianity is in the cross hairs, and that we need to fight back.” As a Christian and the son of a pastor, Alberta knows the movement he is talking about, and has just published a book on the subject. “When Trump pitches himself as a strongman,” he says, “as a would-be authoritarian, what these people hear is, desperate times call for desperate measures.” White evangelicals would “gladly embrace a lurch toward authoritarianism if it meant preserving what they see as a Christian America, rather than lose in a liberal democratic fashion.” Trump’s supporters hear his talk of dictatorship and say “Good! It’s about time.”

Many Trump supporters and surrogates provide lurid examples of what Alberta is talking about. A year ago, Gavin Wax, the leader of New York’s Young Republicans, used exactly the language of Goebbels when he proclaimed “We want total war!” He came back to the idea recently. “Once President Trump is back in office,” he said at a recent gathering to great applause, “we won’t be playing nice anymore. It will be time for retribution.”

Underneath this fanaticism lurk many of the same factors that fueled the Nazis nearly a century ago — a similar sense of economic dispossession and loss of status, brought on by long-term socioeconomic and demographic trends.

Trump’s base is largely made up of working-class white people. The percentage of whites in America is declining, while income inequality has increased and upward social mobility has fallen sharply since the 1980s.

One result is that working-class people, both whites and people of color, struggle with financial stress, lack of healthcare, poor physical environments and limited career prospects. This has contributed to an unprecedented political divide based on educational level: people with college degrees, including whites, now vote heavily Democratic, people without them vote heavily Republican.

These elements provide the fuel for Trump’s movement and supporters — a pervasive feeling of humiliation and victimization. Nelson Mandela once said, “There is nobody more dangerous than one who has been humiliated.” The history of fascism bears him out. The historian Robert Paxton wrote that fascists were marked by their “obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood,” for which the solution was “purity” and “internal cleansing and outward expansion” pursued with violence and no “ethical or legal restraints.”

In the 1920s and 1930s, fascism rose in countries that had been humiliated by military defeat and its aftermath. Its militias were young men with limited job prospects and limited futures in devastated economies. They thought their enemies were criminals, traitors or a different race, or all three. They used violence to “purify” their societies of “Jews” and “November Criminals” (the Nazi term for politicians who signed the Armistice and brought Germany full democracy in 1918).

Trump has gone all in on the “purity” theme lately too. He recently told a rally in New Hampshire that immigrants from Africa, Asia and South America are “poisoning the blood of our country.” This talk resonates with white people who fear becoming a minority, with Christians dismayed by living in an ever less Christian country, with working people who feel relegated to the lower rungs of the status hierarchy. For them, Trump’s fascism means vindication and “restoration” of the country as they imagine it should be.

IS AMERICA DOOMED TO GO THE WAY of Hitler’s Germany or Mussolini’s Italy?

Many commentators seem to think so. Robert Kagan of the Washington Post attracted much attention recently with an opinion article arguing that we are months away from a dictatorship, and that there will be little opposition to it when it comes. Liz Cheney has been sounding much the same warning. Determined to prove Kagan right, Sen. J.D. Vance (R-Ohio) has demanded that Kagan be investigated for inciting insurrection.

The junior senator from Ohio, a Yale-trained lawyer, provides evidence that there will be virtually no opposition to a Trump dictatorship from anyone within the Republican Party, which is split between those who lack the courage and moral principle to oppose authoritarianism, and those, like Vance, who enthusiastically welcome it.

But America is a big, diverse country. Over two centuries of representative politics (and at least about 60 years of being a full-on democracy) have implanted ideas of popular participation very deeply in the American mind. Despite Trump and his supporters, America has strong antibodies against authoritarianism in its national bloodstream.

Let’s take a basic cultural point: Social science data regularly show that in almost all areas of life Americans are the most individualistic people in the world. European and Asian authoritarians have the benefit of people more willing to accept orders from their governments. Sometimes, as with the COVID-19 pandemic, this ingrained American individualism is a problem. But faced with an authoritarian government, it is a plus.

Look at what has happened in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The authoritarian response to Dobbs in red states has run up against a wall of noncompliance. There were more abortions in the U.S. in the year following Dobbs than in the year before. The shredding of women’s rights by a Republican-packed Supreme Court turned out to be a boon to Democratic election prospects and causes in 2022 and 2023, even in red states such as Kansas and Ohio. Americans will simply not comply with orders they don’t like.

The civil rights movement provides another example. The Jim Crow South was a zone of authoritarian, one-party states, with the rule of a small minority enforced by violence and corrupt election practices. Its main goal was to preserve racial segregation, but in some states measures such as poll taxes kept more white than Black people from voting. But this system was eventually overthrown by an internal resistance movement.

In the civil rights movement, even the ways in which Americans are less individualistic than international norms — in their commitments to churches, to causes and to voluntary organizations — proved to aid resistance to authoritarianism. There is reason to expect the same trends on a national level if Trump is elected president again.

There are other factors which will also limit Trump’s authoritarian efforts. Trump has proven himself to be a spectacularly incompetent and undisciplined executive. He lacks the cunning and determined purpose of effective dictators. In a new administration he will surround himself with clowns on the order of Michael Flynn or Rudolph W. Giuliani. Even if Trump and his allies try to dismantle much of the federal government, they’ll create chaos and weaken the government’s capacity to enforce the president’s will. State governments, at least in blue states, will be effective centers of resistance.

It is very unlikely that by the end of this decade the United States will look like Viktor Orban’s Hungary or Vladimir Putin’s Russia, let alone like Hitler’s Germany.

But freedom from a Trump dictatorship will not come without a struggle, and not without suffering, especially for the most vulnerable: the working poor, people of color, migrants and refugees, women who need abortions. In the coming November election, it would be far better to inflict a ballot-box defeat on Trump and his ilk, one decisive enough to push the Republican Party toward its own internal denazification. That, more than anything else, will save us from fascism.

Benjamin Carter Hett is a professor of history at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, CUNY, and the author of “The Death of Democracy” and “The Nazi Menace: Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin, and the Road to War.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.