‘When it’s someone you know, it puts a face on shootings’: For Assembly speaker, gun control fight is a personal one

Reporting from Sacramento — In adopting a sweeping package of gun control laws this summer, many California lawmakers focused on the sobering statistics — the large number of shootings that they say represent an “epidemic” of gun violence.

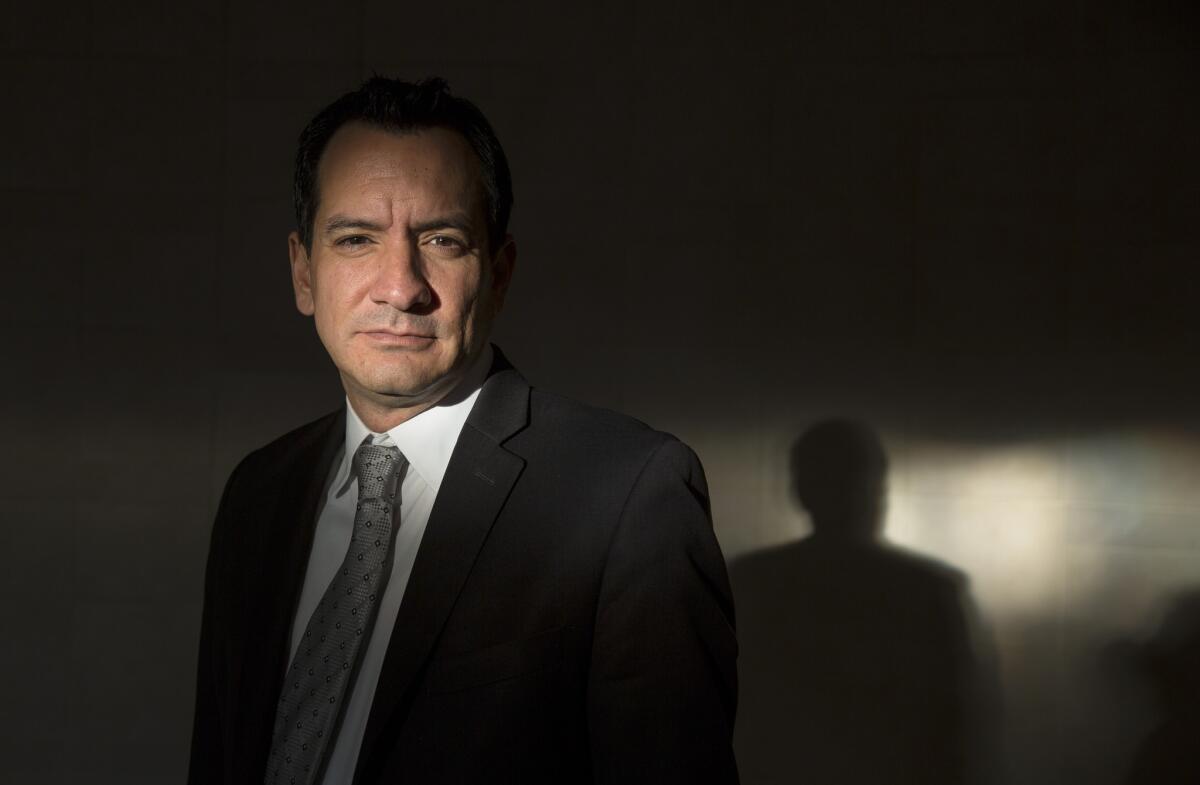

Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon also saw faces: those of his relatives, who were killed by guns.

During a recent Assembly session, the Democrat from Paramount acknowledged the personal toll that gun violence has taken on his family.

“None of us are immune from the tragedies that guns deliver every day in communities throughout our state,” he told his colleagues. “In my own family, five of my relatives have been shot. Three were killed.”

The dead include a teenage cousin, Armando, who was shot to death in 1997 near a food stand on Sunset Boulevard in Echo Park, Rendon said later in an interview with The Times.

Nick Wilcox, co-chairman of the California Chapter of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, credits the Democratic leader with playing a role in getting a package of seven gun control bills approved by the Legislature in June and signed by the governor.

The bills included a ban on large-capacity magazines and semiautomatic rifles with detachable magazines, and a requirement that those who buy ammunition undergo a background check.

Having personal experience with gun violence can’t help but focus one’s attention on the issue, Wilcox said.

He knows firsthand. He became an activist after his college-student daughter, Laura, was shot to death in a Northern California office by a mentally ill man with a semiautomatic weapon.

“It certainly forces you to take the issue seriously,” Wilcox said. “We do this work in [Laura’s] name. We think of her every day. We try to leave the world a little bit safer.”

In passing the gun control measures, lawmakers cited sobering statistics: From 2002-13, some 38,570 Californians were killed by gun violence.

In just 2013, firearms were used to kill 2,900 Californians, including 251 children and teens. That same year, 6,035 others in the state were hospitalized or treated in emergency rooms for non-fatal gunshot wounds, including 1,275 children and teens.

Rendon said such numbers, while horrifying, can be mind-numbing and hard to fully grasp.

“There is nothing abstract about Armando,” Rendon said. “In this country, a number of people are killed each year and I guess that can be abstract at times. But when it’s someone you know, it puts a face on shootings.”

Armando was 16 when he was killed. He had gotten into some trouble and had been sent to live with Rendon’s parents while Rendon, who was a decade older, was away at graduate school, the assemblyman said.

“He stayed in my childhood room,” Rendon recalled. “He liked sports. He liked games and a lot of things that young teenage kids like.”

On the evening of April 8, 1997, Armando and some friends had gone to Burrito King, a popular food stand in Echo Park.

The coroner’s report said police suspect Armando was spray painting graffiti on a wall on Alvarado Street when someone fired a gun from a passing car, hitting Armando in the back of the head. The report called the shooting “gang related,” and said a suspect was taken into custody.

“He was certainly getting in trouble and hanging out with the wrong crowd,” Rendon said. “The crowd he was hanging out with was in gangs. I don’t know if he was.”

Rendon remembers attending his cousin’s funeral at an East Los Angeles Cemetery and coming to the chilling conclusion at the time: “This can happen to any family.”

Eight months later, the family held another funeral, this time for Charles Martinez, the 38-year-old estranged husband of another of Rendon’s cousins.

On Christmas morning, Martinez was shot four times, including twice in the abdomen, as he stood next to his car in a residential neighborhood of Montecito Heights, according to the Los Angeles County coroner’s report. He was pronounced dead upon arrival to Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center. The autopsy report said a .45 caliber pistol was found at the scene and Martinez was believed to have been shot by a man with whom he had a dispute.

Another Rendon cousin, JoJo Martinez, was shot to death in 1995, but details were not readily available.

Rendon said his cousin Michael was just 15 when he was shot in front of the Atwater Village apartment of a friend, who was also hit by gunfire. But Michael survived the shooting two decades ago.

“He was innocent,” Rendon said. “That was a drive-by. He was just in his front lawn and some guys came by and shot him.”

He remembers visiting his cousin in Huntington Memorial Hospital where the youth had to lay on his stomach because his back had been sprayed by pellets from a shotgun.

“My cousin Michael ended up in the military,” Rendon said. “He’s a great guy who has a family now and lives in Los Angeles. He’s doing quite well.”

An uncle also survived a shooting, he said.

All of the incidents taken together — but especially the death of Armando — helped shape his attitude about guns, Rendon said.

“Obviously what happened to my cousin Armando means a lot to me personally because he was close to me,” Rendon said. “It was part of the equation, but not the whole thing.”

He said the current spate of shootings, including the mass murder of 14 people by terrorists in San Bernardino, has further convinced him that more needs to be done.

In June, after 49 people were shot to death in an Orlando, Fla., nightclub, Rendon was one of a small group of lawmakers who attended a rally by the group Moms Demand Action on the steps of the Capitol to call for tougher laws.

One potential obstacle was Gov. Jerry Brown, who had vetoed gun control bills in the past on grounds they did not improve public safety enough to justify taking away privileges of law-abiding gun owners.

Amid concerns over the prospects of the new batch of state bills regulating guns, Rendon and Senate Leader Kevin de León secretly met behind closed doors with Brown on the day of the rally to make their case.

Two days later, Brown signed seven bills.

Rendon cites the one month he spent in his Los Angeles district during the Legislature’s summer break in July as proof that gun violence remains an epidemic.

“We had eight or nine shootings in my district just while I was home for the break,” Rendon said. “It’s too much.”

Follow @mcgreevy99 on Twitter

California lawmakers pass unprecedented package of gun control bills

Gov. Jerry Brown signs bulk of sweeping gun-control package into law, vetoes five bills

Leader of effort to overturn gun control laws is enlisting firearms shops for help

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.