At least two hours have gone by in the Pistol 101 class, and no student has fired a bullet or even picked up a gun.

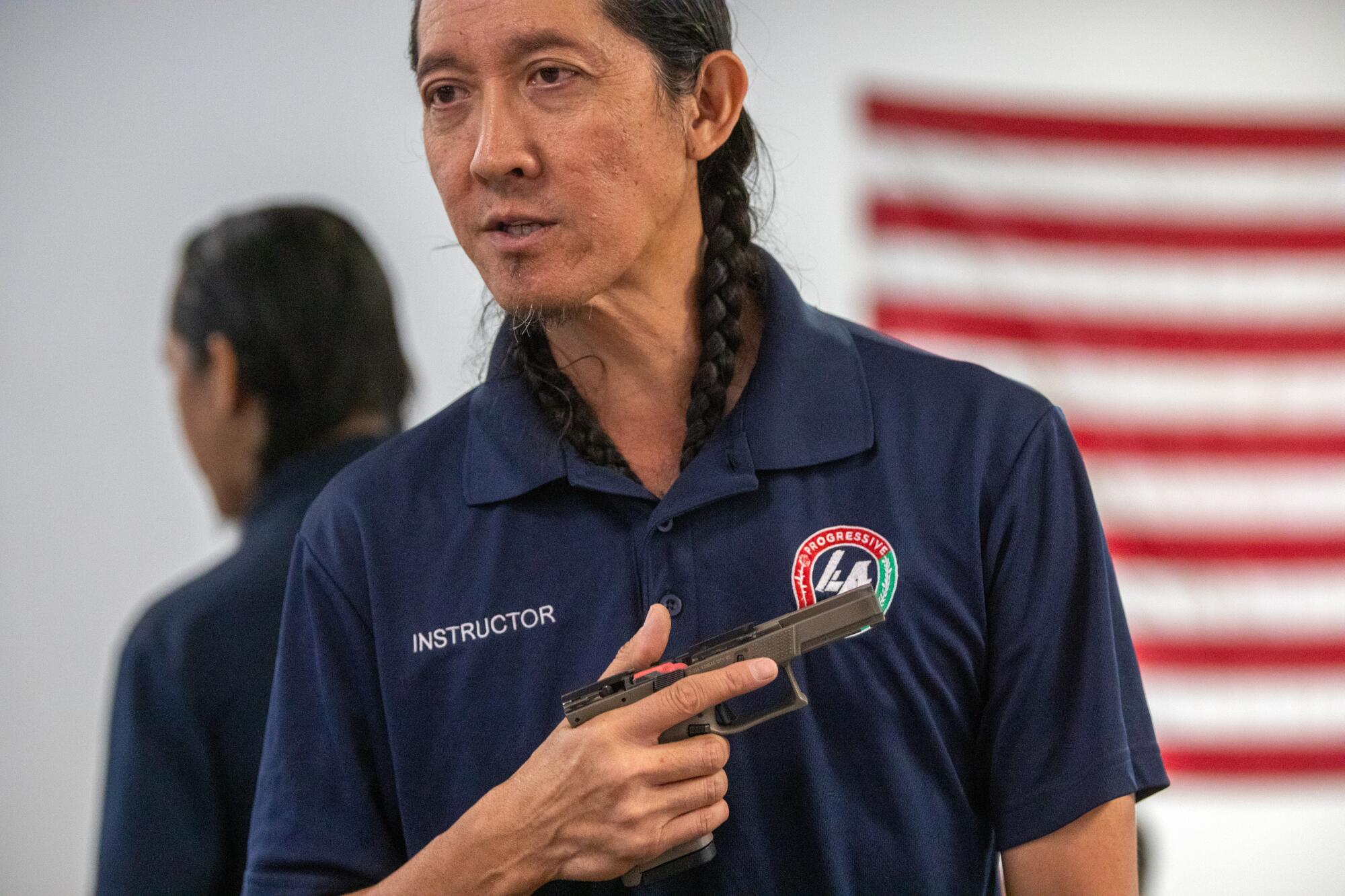

This isn’t a lesson for anyone eager to pull the trigger. Tom Nguyen’s teaching style is patient, aimed at demystifying an object many of his students have spent their lives fearing, even hating.

Something of a leftist firearms whisperer, Nguyen pokes fun at stereotypical American gun culture, mocking “alpha male” behavior and the John Wick film franchise with its video game levels of violence. Owning a gun doesn’t have to define your personality, he preaches, and it doesn’t mean you have to seek conflict.

“Being peaceful,” he says, “is not the same as being helpless, or harmless.”

A wiry longtime martial arts practitioner who sometimes wears his hair in long pigtail braids, the 53-year-old Nguyen plays the role of firearms sensei. But unlike the “gun fu” on display in the Wick franchise, Nguyen teaches form and thought over sudden bursts of close-quarters violence. Lessons often touch on focus and intention.

Among the students paying rapt attention inside a Norwalk martial arts studio is 42-year-old Nikki Shrieves, who wears a sweatshirt with “decolonize” written on the back over and over again, each iteration a different color of the Pride flag.

She trembles slightly as Nguyen places a disassembled Glock on the table in front of her. Nguyen knows why the weapon fills her with dread, so he breaks it down into its components: a spring, a slide, a barrel.

“A gun is a tool to put holes in things,” Nguyen says in his gentle rasp that sometimes takes on a surfer bro affectation.

Gun ownership has boomed in the U.S. over the last several years, including in California.

Among those first-time gun owners are L.A. liberals, and more and more, those rookie shooters seek out Nguyen, who started teaching basic pistol courses in 2020 under the banner “L.A. Progressive Shooters.” He meant that adjective as a beacon to some and a barricade to others.

“You can come as you are, and you don’t gotta bite your tongue and pretend you’re someone else that you’re not,” he says. “I already knew I was turning off the majority of the gun world, but that’s not who I’m here to serve.”

While he rejects what he describes as stereotypical American gun culture — a nationalistic, conservative space with little room for diversity of thought or appearance — Nguyen says he’s also trying to dispel the inherent disgust some left-leaning friends have for firearms.

“It’s always like a dirty secret. I always feel like, before 2020, being a gun owner in liberal progressive spaces was like being in the closet,” he says. “Like you didn’t want people to know you had a gun because you would be judged or looked at a certain way. Like, is there something wrong with you?”

Nguyen did not invent the left-leaning gun group. The Pink Pistols, John Brown Gun Club and the Socialist Rifle Assn. have existed for decades. But those national organizations sometimes come with a slightly militant bent, whereas Nguyen more occupies the role of the lefty gun instructor next door.

Sometimes, Nguyen sounds like a yoga instructor, talking to students about their breathing rhythm as they squeeze the trigger. He’s neither surprised nor bothered when a student breaks down in tears the first time they pick up a gun.

“If you’re nervous, you’re my favorite kind of student,” he says. “It means you’re aware.”

Cognizance of the power of a firearm is a critical part of gun ownership for Nguyen, who is all too familiar with their devastating potential. He’s seen a handgun steal a life. Once, a bullet nearly came for him.

Growing up in Irvine, Nguyen first touched a gun when he was 15. His father’s weapon wasn’t stored properly, not locked in a case, out of the reach of his children. Nguyen said holding the handgun in front of some high school friends made him feel “powerful, just like my movie heroes.”

Right up until it went off.

“To this day, I don’t know how I didn’t shoot my friend,” Nguyen tells his students. “The bullet went over his shoulder and right into the wall.”

Nguyen thinks the weapon was defective — a loose firing pin — and it discharged as he racked the slide.

Years later, Nguyen says, bullets interrupted a meal with his family when a gunman chased a man into a Garden Grove pho restaurant, emptying a magazine into his back. The victim, Thanh Chi Nguyen, would not survive. The shooter, Victor Tuan Nguyen, was convicted of murder. He is not related to either man.

Despite the traumatic events, Nguyen says he continued to “worship” guns. He bought a rifle when he was 18 and would sometimes go shooting with friends and cousins in remote parts of Orange County.

“Guns were so glamorized. It was probably my biggest obsession ... dreaming about guns, drawing pictures of them,” he says.

The child of Vietnamese refugees he describes as “strict immigrant parents,” Nguyen says he had “three choices” when he began at UC Irvine a few years later — “be a doctor, a lawyer or an engineer.”

But Nguyen “flunked out,” leading his parents to kick him out of their home. It wouldn’t be long until Nguyen found himself holding a firearm again.

“I’m homeless now. No future prospects. My girlfriend at the time dumped me. So, age 21 ... I finally got to buy my first handgun for my very own personal use,” he says. “And that was with the intention of committing suicide.”

Nguyen wrote a note and knew where he planned to fire the fatal shot. But he also said he ruminated on his legacy, fearing his family would see him as a “quitter.”

A month passed, then a year. Slowly, Nguyen began to process both his depression and the rift that opened up with his family. He got rid of the gun, but stayed interested in shooting, buying a few more weapons and taking lessons at gun ranges from current and former police officers.

Eventually, Nguyen returned to UC Irvine and started selling off his firearms to help cover tuition. He thought he’d “never touch” a gun again, until 2019, when he lost a girlfriend but gained his first student.

He was down to one firearm — a Glock 26 he had kept hidden from his “anti-gun” girlfriend — but after the break-up, Nguyen’s ex planned a long road trip along the Pacific Coast.

Concerned about his ex’s ability to defend herself, Nguyen taught her some pistol basics, taking the same methodical approach his future students would come to know.

The two started going to gun ranges, and Nguyen posted footage of their range visits to Instagram. At the time, Nguyen was running an account for a grassroots marketing team that promoted events run by the L.A. Philharmonic and Hollywood Bowl. With most of his followers based in liberal L.A., he anticipated vitriol.

The first message Nguyen received, however, was a request for a lesson. The potential student was a musician who had just bought a gun for home defense following the at times violent street protests after the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

“He grew up in Venice in the ’90s. Drive-by shootings. He absolutely hates guns. But he’s like: ‘Yo, I’m married now. Even though I don’t like ’em, I don’t wanna be the only one not to have one,’” Nguyen says.

From there, stories of Nguyen’s firearms proficiency spread by word of mouth. “Tom shoots guns” became an excitably whispered phrase among friends in L.A.’s local music scene, Nguyen said.

Soon, he was inviting potential students over to his home and walking them through the primordial version of an “L.A. Progressive Shooters” lesson.

The timing was perfect, if bittersweet. While the pandemic had destroyed his business promoting live events, 2020 also happened to be “the year everyone bought guns,” Nguyen says.

That year the California Department of Justice issued roughly 511,000 “firearm safety certificates,” which must be obtained to legally buy a gun in the state; that was more than the department issued in the prior two years combined, records show. The number of registered gun owners in California jumped from 2.3 million in 2018 to nearly 3.5 million at the start of this year.

I was among those new gun owners. In 2021 — after watching colleagues hide from the violent mob on Jan. 6 and remembering I have a habit of writing about angry men with access to weapons — I walked into a Burbank gun store to pick up my first handgun.

The weapon was transferred to me by the man who taught me anything I ever knew about guns, my father.

A National Rifle Assn.-certified instructor and former New York City Police detective, the elder James Queally (though everyone calls him Jim) is as patient a teacher as one could ask for and a stickler for safety, much like Nguyen.

But I could see how the Staten Island, N.Y., gun club where he often corrects my stance and habit of drifting shots low and left during visits home could feel like hostile territory to some of Nguyen’s students, and a less than ideal space for a journalist with a California mailing address. One guy made the sign of the cross when I told him I’d moved to Los Angeles. “Let’s Go Brandon” stickers are visible, and conversations about my profession can get uncomfortable when the range members, many of them ex-cops, realize I often write about law enforcement misconduct.

My foray into gun ownership is part of a larger trend. Last year, a national NBC/Wall Street Journal poll showed 52% of registered voters said someone in their household owned a gun, up from 46% in 2019. The share of Democrats who answered “yes” rose from 33% to 41%.

Wanting to improve his firearms skills as he planned to launch his classes, Nguyen said he stumbled into a 2nd Amendment-focused Facebook group that was intended to be welcoming to Asian gun owners.

A few days in that space made Nguyen more certain than ever that he needed to create one of his own.

“It was no different than the kind of attitudes I’ve seen in the rest of the male-dominated gun world. They were right wing. They were conservative. They were homophobic. They were transphobic, misogynist,” he said.

Michael Schwartz, executive director of the San Diego County Gun Owners Political Action Committee, said that while he’s supportive of Nguyen’s mission, he thinks his assessment of the “traditional” gun owner leans too heavily on tropes.

“The stereotype is gone. Firearms, as a hobby, are very common in the Asian community and the Hispanic community, and that’s not who we think of,” Schwartz said. “Growing up, a gun owner was somebody out of ‘Duck Dynasty.’”

In the months after his Facebook misadventure, Nguyen turned to the traditional gun world for training and became a certified instructor with both the NRA and the U.S. Concealed Carry Assn. By September 2020, he launched “L.A. Progressive Shooters.”

Nguyen says he’s averaged about 300 students annually since then, for classes ranging from basic pistol use to proper home defense to obtaining a concealed carry permit.

Among those who might have never picked up a weapon if Nguyen wasn’t around is Nikki Shrieves, the woman who broke down in his Norwalk class.

Shrieves said she got serious about learning about firearms in 2020, unnerved by the violent rhetoric of some of then-President Trump’s supporters and the actions of law enforcement during protests that summer.

“I want to know how to protect myself, to protect the community I live in,” she said. “I know [the police] are not out there to protect me or my community.”

Despite the tough talk, it was Shrieves who began to tremble when Nguyen placed a disassembled Glock in front of her. As he taught the five-student class how to load the weapons with dummy rounds, Shrieves began crying and placed the inert weapon back on the table.

She soon told the class that, when she was young, her uncle was murdered during a carjacking in Koreatown. For the longest time, the guns in her house were a source of fear, a hot stove she was afraid to touch.

“In my head I’m like, ‘What if I somehow make the gun blow up and then I hurt myself or somebody next to me?’” she said.

But by the time she got to the range, Shrieves said, Nguyen helped her work up the nerve to empty three whole magazines into a target. A small victory to some, but huge progress for her.

1

2

1. Nikki Shrieves takes aim during target practice. 2. Some of the .22-caliber rounds of ammunition used during the firearms education course taught by Tom Nguyen.

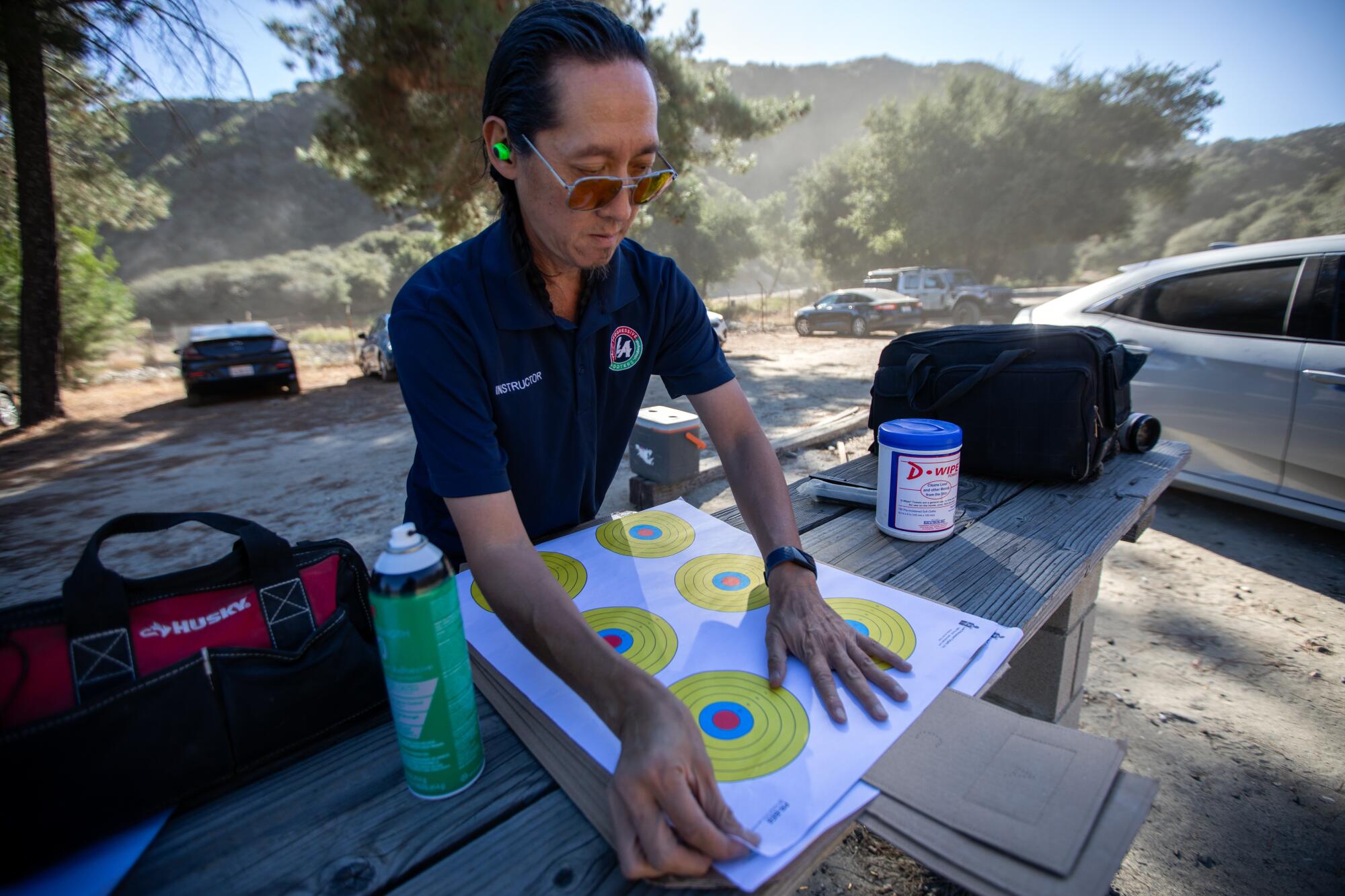

Nguyen trains his students in Burro Canyon, a shooting park nestled deep in the San Gabriel Mountains near Azusa. In the yawning expanse, the only constants are Nguyen’s voice and the occasional thunder of gunfire.

Jasmine Quezada, 32, of Boyle Heights was among those students in the mountains on a windy Sunday. She also sought out Nguyen’s class in 2020, unnerved by that summer’s protests. She began thinking about protecting herself. Her husband owned a firearm, but Quezada hadn’t ever touched it.

“I don’t like having it in my house,” she said. “But it’s much more unsafe for me to not know how to use it.”

After a few minutes next to Nguyen, Quezada’s fear turned to excitement as she felt aware of the “power in your hands, but not feeling it as a weight, but as a thrill.”

Standing just off to each shooter’s left, Nguyen offers gentle guidance on stances and compliments students on shots that hit near the bull’s-eye while telling them to focus on their mechanics rather than the result. When one shooter’s form starts to break down, he advises the student to lower the weapon, take a break, relax. There’s no need to empty the magazine quickly.

When one student appears to tense up with each trigger pull, Nguyen offers advice that could refer to meditation as easily as firearms, urging them to stop anticipating each shot and “let the gun decide.”

The advice worked for Quezada. “You know that there’s going to be a recoil. You can try to prevent it and you can try to brace yourself against it, or you just let it happen to you,” she says.

Despite the political name of the group, gun politics themselves rarely come up in Nguyen’s classes. Some of his students, like Quezada and Shrieves, adhere to classic liberal stances on firearms: They support an assault weapons ban and believe ownership should be strictly regulated. But in a world where Quezada sees her political opposites as increasingly racist and hostile, she’d rather be able to protect herself.

“If I ever have to use my firearm … I want to be able to defend myself, but I also want to be able to defend someone more marginalized than I am,” Quezada said, adding that she enjoys “shattering the illusion” that all leftists are latte-sipping, gun-fearing academics.

“I’m a short, brown Latina who owns a gun, and I like making it known that there are people like me out there,” she said.

Nguyen’s stances are a little more centrist. He rolls his eyes at the arguments most of his friends make in response to mass shootings, correctly noting that handguns kill far more Americans per year than rampaging gunmen armed with assault rifles. He has reservations about gun control legislation, fearing it would be disparately enforced against marginalized communities.

To Nguyen, the journey in his classes is about past trauma, not politics. The moment Shrieves broke down in his class might have been embarrassing at a typical range. In Nguyen’s class, it’s encouraged.

“She’s not the first person to cry in my class. And I’ve cried with some of my students,” he says. The goal is transformation. “Can I help you move past this very painful scary object and see it in a different light?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.