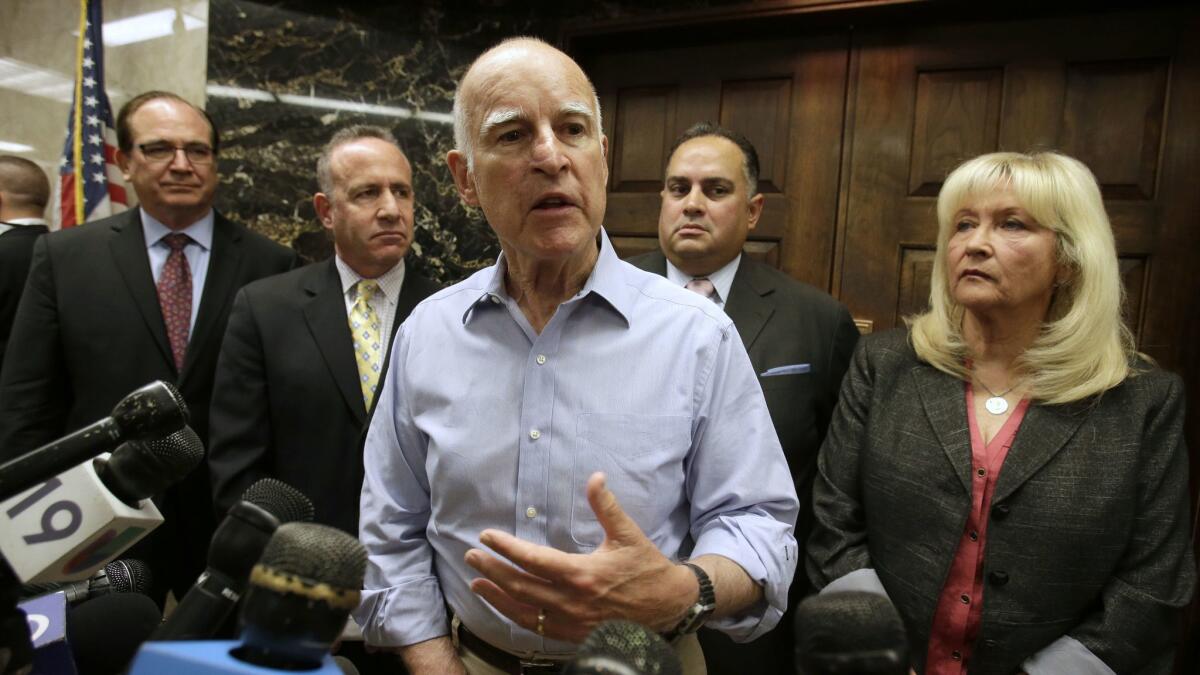

On crime and punishment, Gov. Jerry Brown leaves behind revised rules and a new focus on redemption

Reporting from Sacramento — When Gov. Jerry Brown’s final term in office ends next week, he will leave behind a California criminal justice system infused with a new commitment to second chances, a shift away from an era in which tens of thousands — many poor, most black or Latino — were imprisoned with little opportunity to turn their lives around.

“It’s called hope,” Brown said in a late December interview. “One hundred fifty thousand young men with zero hope bolsters the gangs, leads to despair, leads to violence and makes the prisons very dangerous. Many of them, the majority, will get out anyway. And they’ll get out as very wounded human beings.”

The governor’s attempt to unwind the old approach stands in contrast to his legacy from the 1970s. Despite a professed belief in redemption, no governor did more to launch the state’s tough-on-crime era — signing a seminal law four decades ago that paved the way for strict sentences, even for nonviolent crimes.

Brown’s decision to change course, promoting measures over the last eight years to revisit the need for long prison sentences, was driven by legal mandates as much as morality. Key, too, was the Democratic governor’s reliance on research and data that concluded much of the old thinking on crime and punishment had been wrong.

“He’s really followed the science of criminal justice,” said Jeanne Woodford, a former state corrections secretary. “That’s very refreshing, as opposed to people making decisions based on their worst fears.”

In recent years, Brown supported legislation or ballot measures that downgraded drug crimes, offered some inmates new opportunities for parole and prevented or limited the detention of children and teenagers.

He helped craft a sweeping plan to grant judges greater discretion over California’s bail system, eliminating cash payments as a condition of release from jail. He appointed hundreds of jurists to local courts who share his vision of considering options other than lengthy incarceration. And for those who turned their lives around, Brown offered clemency — he approved more requests than any governor in state history.

But to some, the four-term governor made things worse when taking office in 2011. Critics cite an uptick in violent and property crimes in some communities as evidence that leniency won’t work. Brown’s signature on a so-called sanctuary state law in 2017 limiting local law enforcement cooperation with federal immigration agents remains the focus of sharp debate. And in recent weeks, the California Supreme Court blocked 10 commutations he gave to felons.

“Rather than doing more, he could have done less,” said Michele Hanisee, president of the Los Angeles County Assn. of Deputy District Attorneys, a group that’s been sharply critical of the governor. “Less would have been better.”

Others in law enforcement credit Brown for a willingness to listen and, when possible, compromise. And those who have worked with him cite the experience he brought to his final two terms after serving as mayor of Oakland and state attorney general.

“It gave him a perspective that we haven’t had from any other governor,” Woodford said. “He’s very politically savvy because he keeps everyone at the table.”

Brown credits judges, not politicians, for the push to reshape the state’s criminal justice rules.

“Without the federal courts intervening, there would be no chance for the California Legislature to make the reforms that we made,” he said.

Key to those efforts was a 2011 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld a lower court’s order to release some 46,000 state prison inmates. Years of overcrowding, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, led to inadequate medical care and “needless suffering and death.”

Prisoner rights advocates weren’t expecting Brown, who defended the state as attorney general, to be an ally.

“He fought the prison overcrowding case with everything he had and refused to believe that there was a problem,” said Natasha Minsker, director for the ACLU of California Center for Advocacy and Policy. “It took a 180-degree turn when he became governor and the Supreme Court said, ‘No, this is the end of the road. There are no appeals left.’”

The ruling, combined with a projected $27-billion state budget deficit he inherited upon taking office, opened the door for something radically different. Brown and lawmakers crafted “realignment,” a plan to divert felons convicted of lower-level crimes to county jails. Local officials received state dollars that could offset some of the costs. Counties were tasked with additional supervision duties and more offenders were monitored through probation.

By realignment’s six-month anniversary, there were 21,000 fewer inmates in state prison. But the effort was sharply criticized by law enforcement groups and Republican lawmakers who predicted mayhem in local communities. They warned that officials would be overwhelmed by dangerous criminals who would otherwise be in prison.

Stanislaus County Sheriff Adam Christianson, who said he was worried that “consequence and accountability” would be “stripped out of the system” under realignment, was a key negotiator with Brown.

“If you really want us to embrace that vision, you need to help us,” he remembers telling Brown.

The governor made a series of unannounced visits to county jails across California in the months following the law’s passage — he didn’t always find a receptive audience. But Christianson applauded Brown’s later efforts to expand local jails and mental health facilities to handle the additional offenders.

“Working with the state can be incredibly bureaucratic,” Christianson said.

The governor, he said, “pushed the state Legislature to come up with a methodology” to help ensure bond proceeds would be available to more counties.

The decree by federal judges to shrink California’s prison population led Brown to rethink the opportunities for parole he helped eliminate in 1976, when he signed a bill to abolish flexible prison sentences. Under that law, judges had diminished power to lessen punishment and the state parole board could no longer release an inmate after a minimum number of years; prosecutors, meanwhile, could demand lengthy sentences.

By the beginning of the 21st century, legislators had greatly expanded the rigid sentencing regime. Prisons were bursting at the seams.

Woodford recalled a visit by Brown to San Quentin when she was the prison’s warden and he was Oakland’s mayor. On a tour of a unit that housed inmates with set sentences — who had no chance at going home early — she remembered Brown as “shocked” by what she described as a criminal justice system that allowed lawmakers “to pile on for political gain.”

In his final term as governor, Brown saw an opportunity for change.

“I will tell you that government best solves problems that it first creates,” he told the California Chamber of Commerce in 2016.

But undoing those laws in the state Capitol, where police and sheriffs flex considerable political muscle, was a nonstarter. Instead, Brown focused on how to incentivize rehabilitation for inmates; he believed prison officials and the state Board of Parole Hearings were best equipped to make decisions about who was ready for life outside prison.

“That’s based on a human judgment of another human being,” Brown told the business group. “And it’s that flexibility and that discretion that adds wisdom to a system, instead of automatic pilot, mechanistic rigidity.”

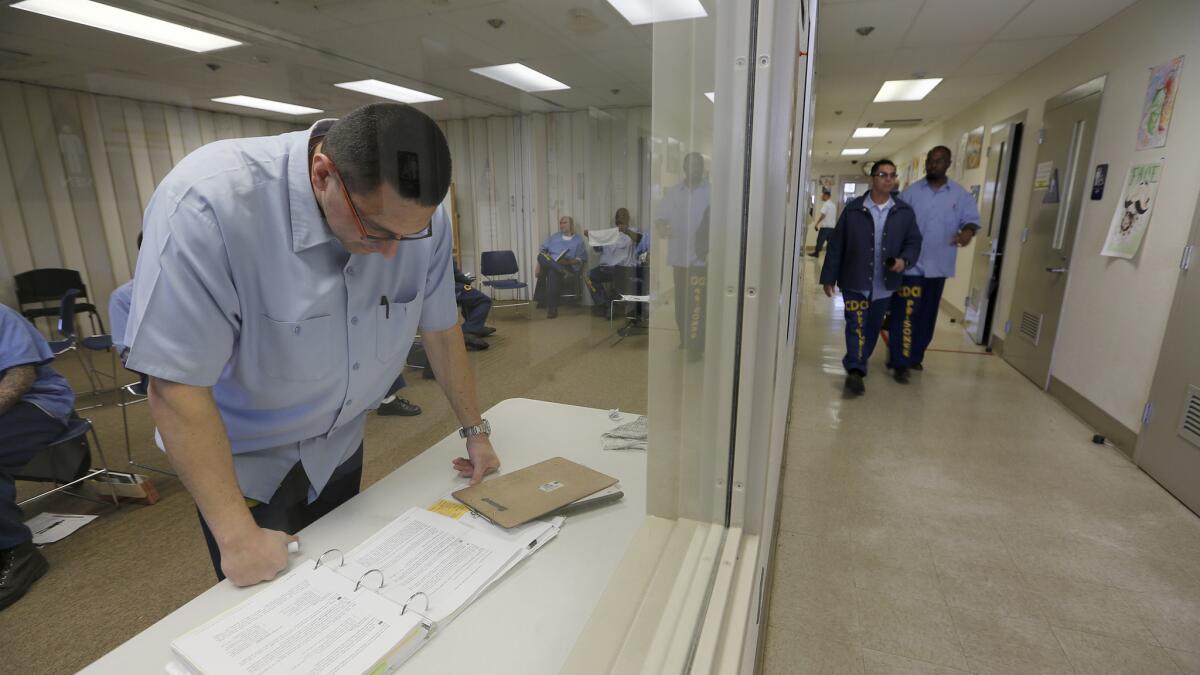

In 2016, Proposition 57 proved to some reform advocates and Democrats that the governor was committed to a path that would prepare inmates for life outside of prison.

State Sen. Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley) said she was struck by how, during the drafting of the measure, the governor visited every state prison, some multiple times.

“As a result, he got more insight into the conditions, the circumstances of the people in prison,” Skinner said. “The more time he spent visiting in prisons, the more that I saw his willingness to really change some of our laws.”

The ballot initiative, which was overwhelmingly approved by voters, expanded the authority of parole commissioners over more cases and allowed prisoners to earn more time credits toward early release if they enroll in drug treatment, anger management classes and educational or vocational programs.

The measure also included a provision to move young people out of the prison pipeline, requiring judges to approve any transfer of juveniles into adult courts — a reversal of a law approved by voters in 2000.

Brown and district attorneys clashed in 2016 over how to define “nonviolent felons” eligible for parole. Some law enforcement officers and prosecutors insisted it would give some violent or serious felons — including sex offenders — a chance for early release.

In January, a judge ruled state officials must give parole consideration to sex offenders. The Brown administration appealed the ruling.

“He promoted it by saying all these people would be excluded,” Hanisee said. “But you cannot blanket exclude sex offenders or third strikers because the way [Proposition 57] is written includes many of them.”

Legislators eager to further transform the criminal justice system found a willing partner in Brown. With a push from Democrats and well-funded coalitions of criminal justice reform advocates, he signed new laws that scaled back mandatory sentencing rules, decriminalized prostitution for minors and sought to protect the rights of young people who have run-ins with the law.

State Sen. Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles) said a confluence of factors may have created the right climate for Brown to act, including a realization that “a disproportionate number of black and brown people represented six, five times their population in state prisons.”

“I appreciate someone who is willing to look at the data and acknowledge that he has some correcting to do,” Mitchell said.

Civil rights groups found Brown willing to revamp other parts of the criminal justice system, too. In 2018, he signed the most expansive police transparency laws in 40 years, giving the public access to internal investigations of police shootings statewide and permitting the release of body camera footage of many of those incidents. The year before, he approved using state funds to help provide lawyers for some immigrants facing deportation.

Lawmakers said Brown was a critical behind-the-scenes force on many bills. In September, he signed a law by Skinner narrowing the scope of felony murder rule, which allowed a defendant to be convicted of first-degree murder if a victim died while a felony was committed, even if the person did not intend to kill, or did not know a homicide took place.

Skinner said the governor signaled to her early in the process that he would support her legislation to spare unknowing accomplices.

“For me it was very important to know that he was supportive and that I had an ally and could call him if needed,” she said.

Gov.-elect Gavin Newsom has praised his predecessor’s “enlightened policies” on criminal justice and pledged to build on Brown’s legacy. But Newsom will likely not be able to ignore a mental health crisis and a growing homeless population. Both are state emergencies that Brown’s critics — and some of his supporters — argue have been exacerbated by releasing more people from jails and prisons to communities with limited housing options and few social services.

The long-term effect of Brown’s efforts remains unclear. A study by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California in 2015 found at least some connection between prison realignment and increased property and auto crimes, but no similar link to violent crime rates. Nor did PPIC researchers find evidence to suggest the policy lowered the chances of a person to break the law again.

Proposition 57, which Brown’s corrections chiefs have been working to implement, is expected to decrease the prison population and temporarily increase the population of parolees, which now stands at an average of roughly 48,000 a day, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Law enforcement groups and Brown could be headed toward another ballot box battle over an initiative that would limit the number of prisoners eligible for early parole under Proposition 57. The Brown administration filed a lawsuit two weeks ago to force the measure off the November 2020 ballot, arguing it was improperly drafted.

Brown argues some unintended impacts from so many sweeping changes to the criminal justice system can be addressed through more cash and cooperation. He said money earmarked in this past summer’s state budget agreement, for example, can be used to combat increased cases of retail theft in communities across California.

“It takes the judges and the prosecutors and the political leaders to have the will to take forceful action but also have intelligent remedies,” the governor said. “Is there a better way to do it? I say there is.”

Follow @johnmyers and @jazmineulloa on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.