More California inmates are getting a second chance as parole board enters new era of discretion

Since the passage of Prop 57 the State Board of Parole Hearings work load has increased to up to 400 hearings a month.

An Alameda County probation report details facts that Kao Saelee can’t change: He was 17 and armed with a sawed-off shotgun when he and three friends opened fire on a group of teens they believed belonged to a rival Oakland gang.

The spray of bullets instead struck Tsee Yorn and San Fou Saechao, both 13. It killed 7-year-old Sausio Saephan, a second-grader at nearby Garfield Elementary School who had tagged along with his older brother and was shot in the neck.

For years, members of the State Board of Parole Hearings could — and often would — deny prisoners early release based on their past, focusing solely on their criminal offense rather than whether or not they’d pose a safety risk in the future.

To inmates, it seemed an unspoken rule: Let no one out.

Now, the board has entered a new era, empowered to grant more offenders a chance at parole after a decade's worth of court decisions and state laws that have broadened its discretion. With the greater legal flexibility, Gov.

Parole commissioners stay away from politics. Jennifer Shaffer, the board’s executive officer, says their only role is to neutrally apply the laws, which have changed the way they evaluate which offenders are too dangerous to let out. The focus is no longer so much on the severity of the crime, as on whether offenders have come to an understanding about why what they did was wrong.

One question, Shaffer said, has become central to weighing whether someone is fit for parole: “Who are you today, and is there any evidence of current violence, current unreasonable risk to public safety?”

That approach, criminal justice experts say, is part of a pendulum swing in California, coming after decades of tough sentencing policies that led to overflowing prisons and a court-ordered cap on the state inmate population.

During his first term as governor in 1977, they said, Brown shifted sentencing power away from judges and parole boards to prosecutors when he signed a law that set fixed, inflexible prison terms for some crimes. Proposition 57, which voters overwhelmingly approved last year, returns some of the board’s discretion by allowing more offenders to trim those sentences, moving up their parole hearings and expanding the board’s authority over a greater number of prisoners.

Brown has said it allows convicted felons to be judged once they have had a chance to change their lives.

The board “isn’t making up the recipe” to the state’s approach to crime and punishment, “but it is the one cooking it,” said Vanessa Sloan, founder and director of Life Support Alliance, which advocates on behalf of inmates sentenced to life in prison.

Through the decades, California’s parole commissioners have been accused of being too lenient on punishment or taking too much of a hard line.

But before Brown’s return as governor in 2011, lawyers and legal experts said, parole boards tended to be vocal supporters of strict sentences, and mainly were composed of former law enforcement officers, elected officials and advocates for crime victims. Many commissioners, if not most, were white men, adding to the lack of diversity.

Brown appointed Shaffer as executive officer of the State Board of Parole Hearings in June 2011 with the goal of “professionalizing the board and making it a strong, independent body,” she said.

Under her direction, the makeup of commissioners has diversified by gender, race and professional background. Shaffer also has been at the helm of major initiatives, spurred by court cases, lawsuits and state laws, that have developed new processes to speed up and increase parole hearings, as well as to release young and elderly offenders.

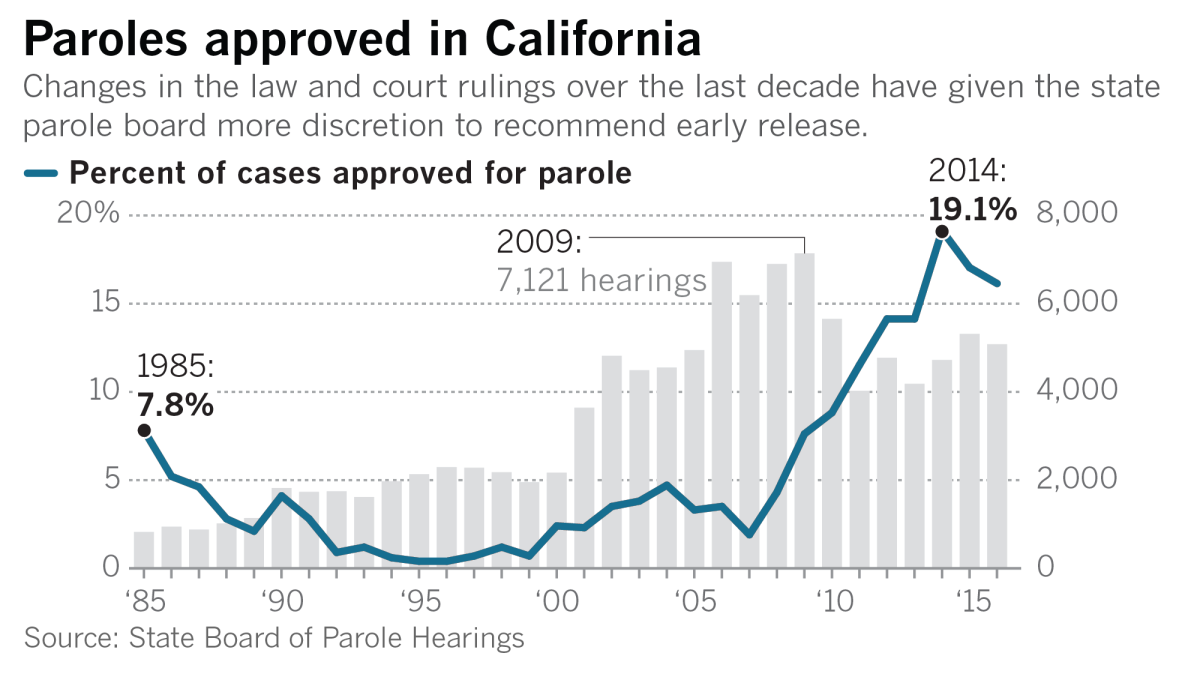

The board now takes up to 400 parole hearings a month including those for older and youth offenders, and prisoners are now more likely granted recommendations for release. Nearly 820 inmates, or 16% of prisoners who had hearings in 2016, were seen as fit for parole that year, compared with 119, or less than 2%, in 2007. Just 16 prisoners, or less than 1% of those who had hearings, were deemed fit for parole two decades ago.

The workload for parole commissioners has increased under Proposition 57, which is expected to trim the sentences of 11,500 prisoners over the next four years.

New guidelines to implement the initiative, which took effect this month, allow most inmates to earn additional time toward completing their sentences, and to move up their parole hearings by earning credits for good behavior and enrolling in career, rehabilitation and education programs. They also expand parole consideration to prisoners whose primary sentences are for crimes not designated as “violent” under California law, and who have served the full term for those offenses.

Corrections officials previously offered parole eligibility only for nonviolent inmates who had been charged with a second strike under the state’s three-strikes law, and served 50% of their sentences. Of those nearly 6,200 referrals, 28% have been approved for release.

Lawyers and legal experts first started noting the board's exercise of broader discretion when it came to the parole hearings for offenders sentenced to life with the possibility of parole.

“It used to be, you could ask a life term inmate if they had ever known anybody that had received a [parole] date and the answer was ‘no,’” Shaffer said. “Now there is not a single life inmate, I believe, who doesn’t know somebody who has gotten a date.”

Commissioners attribute the seismic shift to a 2008 decision in the case of Sandra Davis Lawrence, who was declared suitable for parole over former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s objections nearly 24 years after she fatally shot and stabbed her lover’s wife with a potato peeler.

In the 4-3 ruling, the California Supreme Court found inmates could not be denied parole based solely on the viciousness or lethality of the crime. Shaffer said parole boards must instead take into account whether the defendant would pose a safety risk to the public if released.

“That really changed the focus of our hearings. From, ‘You did what? Tell me about the crime,’” Shaffer said. “To, ‘Who were you then? Who are you today and what’s the difference?’”

But lawyers, former board members and inmate advocates say the change of culture goes beyond the rulings. They credit Brown for appointing practitioners like Shaffer who have honored the changes in the laws, and they point to Shaffer for bringing the board into a new era of transparency.

At a Senate confirmation hearing in late June, parole board commissioner Randolph Grounds, a warden at various prisons over five years, seemed to reflect the board’s new attitude.

“Yes, as a warden you have to keep people inside, but the mindset is all about moving people forward,” he said, emphasizing the need to place inmates in programs and prepare them to enter the community.

Two weeks later, Grounds was asking the questions at California State Prison in Folsom. In a cramped room, he and two other commissioners sat across from Saelee, who had served 10 years in prison for the drive-by shooting that took Saephan’s life.

Saelee, a refugee from Thailand who is now 31, told the panel he grew up with an abusive father. He said he had been bullied in school for his poor English and for wearing donated clothes until he started fighting back. He admitted he burglarized homes and associated with gangs in his teens but had not before been arrested.

The day of the killing, he had been playing video games at a laundromat, when a friend asked him for help retaliating against a rival gang member. They went out in search of the young man and fired at a group of teens, though they were not sure if their target was among them. They celebrated after they got away, Saelee said.

“It was heartless,” he said, wiping away tears. But he said he did not realize the weight of his actions until he was behind bars, where he stopped doing drugs, underwent therapy and became a youth counselor.

At the end of the two-hour hearing, and without opposition from an Alameda County prosecutor on the case, the panel of three commissioners recommended he be granted parole. Grounds urged Saelee to remember the lessons he has learned.

“We don’t want any other victims,” Grounds said. “We don’t want no other fallout. What we want is healing.”

Decisions on the sentences of life inmates must go to the full board for approval, to a legal office for review and then to the governor who can reverse it and send it back to the board for further consideration — a practice Brown used less than other governors.

But the review process for nonviolent offenders under Proposition 57, which does not include a review from a governor but can be appealed, is facing fire from all sides. These prisoners referred to the board are first screened for the dangers they pose if released, and the review spans an offender’s criminal history, institutional behavior, rehabilitation efforts and any written statements received from the inmate, victims and prosecutors.

Offenders convicted of sex crimes in which there was no physical contact with the victim, such as public indecency or distributing nude photos, and those with a "third strike" for a nonviolent offense argue they, too, should be eligible. Meanwhile, the law enforcement officers, prosecutors and lawmakers who have opposed Proposition 57 from the beginning argue its regulations include loopholes that could make some violent or serious felons eligible for parole.

They warn the review process for such inmates is not as thorough as the hearings for juvenile and elderly offenders, and others serving life sentences, because the proceedings are conducted primarily by deputy commissioners with less experience and amount solely to an analysis of paperwork — and don’t include a hearing.

Sen.

“I am one who most believes in rehabilitation, but I also know that in prison, the capacity to rehabilitate has not expanded much,” Nielsen said. “I also know that in the community rehabilitative opportunities have not expanded much.”

Others counter that it is too soon to know whether the parole board has too much discretion.

“I don’t know if anyone is ever going to be convinced that we have reached the perfect medium,” Loyola Law School professor Laurie Levenson said.

Parole board members say no matter the case, era or governor there is always a strong incentive to get it right, both for the inmate and society. At her confirmation hearing in June, parole board commissioner Patricia Cassady, a former defense lawyer, said she would not want to release anyone she would not want living next to her home.

“It is a weighty decision we make every day,” she said.

Proposition 57, Gov. Jerry Brown's push to loosen prison parole rules, is approved by voters »

ALSO:

Governor's budget gives a glimpse into challenges ahead for prison parole overhaul in California

Debate over sex offenders moves to court as California undertakes prison parole overhaul

Why Gov. Jerry Brown is staking so much on overhauling prison parole

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.