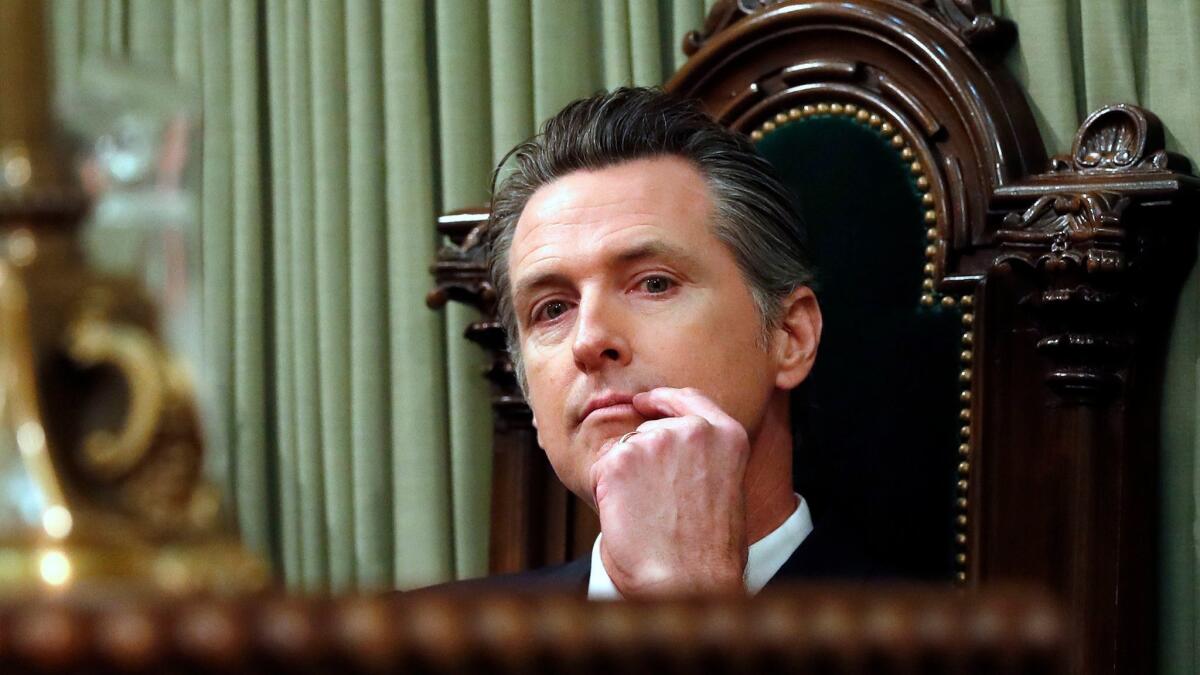

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s opposition to the death penalty appears destined for a test

Reporting from Sacramento — In an executive order last month calling for new DNA tests in the quadruple-murder case of death row inmate Kevin Cooper, Gov. Gavin Newsom said he was acting to ensure that all evidence is examined when “the government seeks to impose the ultimate punishment.”

Cooper’s fate won’t be the last in Newsom’s hands. California is home to the nation’s largest death row with 737 condemned inmates — 24 of whom are convicted of murder and have exhausted their appeals, like Cooper.

For the record:

11:45 a.m. March 12, 2019An earlier version of this story said that 739 inmates are on California’s death row. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation reports there are 737 inmates on California’s death row.

The state has not put a prisoner to death since 2006 because of a series of legal challenges to its method of lethal injection. But Newsom said he expects those court cases to be resolved while he’s in office, clearing the way for executions to resume in California.

“We’re poised to potentially oversee the execution of more prisoners than any other state in modern history,” Newsom said. “Those 24 have gone through their process and many others are right behind them.”

The governor has been open about his opposition to the death penalty, saying that he has the ability under the law to put his beliefs into practice. As lieutenant governor, he was one of a few statewide officials to endorse a failed 2016 ballot measure to abolish the death penalty, while then-Gov. Jerry Brown and then-Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris, who is now in the U.S. Senate and running for president, took no official position.

Newsom directed his legal advisors to assess his options as California’s chief executive, which include the constitutional power to commute death sentences and issue temporary reprieves. But the governor must balance his opinions on capital punishment with the will of California voters, who over the last six years rejected two statewide ballot measures to repeal the death penalty and favored fast-tracking the appeals process.

Newsom has not said publicly what he plans to do, but the governor indicated he may take action in the near future.

“The minute I got elected, in the transition, I prioritized this issue,” Newsom told The Times in a recent interview. “I don’t want to react to something. I want to be proactive. And I have been very proactive in trying to determine what the best path is.”

Since his election, Newsom has sought counsel on the issue of capital punishment from religious leaders, state lawmakers and former governors from across the county, including his predecessor, Brown. He’s also talked with former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, the last California governor to preside over an execution in the state.

Death penalty opponents believe Newsom will not allow an execution to take place while he is in office given his objections to a death penalty process he has said is “administered with troubling racial disparities,” and because of wrongful convictions in the judicial system.

“Sometimes being a leader is leading. I don’t think Newsom will ever put somebody to death,” said Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego), an opponent of the death penalty. “Slavery was once a law and also popular in this country and there were people who stood up and said, ‘No, this is wrong.’”

Former “M*A*S*H” star Mike Farrell, a leading advocate for abolishing the death penalty, said he spoke with Newsom about the issue during the 2018 gubernatorial campaign.

“I don’t believe he will allow an execution to go forward during his time in office,” Farrell said. “That’s me, that’s my sense of the man [from] my conversations with him.”

Farrell was a major proponent of 2016’s Proposition 62, which would have abolished the death penalty for first-degree murder and reduced death sentences to life in prison without the possibility of parole. California voters rejected the measure by a margin of 53% to 47%. Voters narrowly approved Proposition 66, a measure on the same ballot to streamline death penalty appeals.

Two days before the election in 2016, Newsom sent out a tweet calling the death penalty “fundamentally immoral,” and highlighting the case of Alabama prisoner Anthony Ray Hinton, who was sentenced to death for a double murder and released in 2015 after forensic experts couldn’t determine whether bullets from the crime scene came from his gun.

Farrell urged Newsom to take a stand regardless of public perception and said he wants the governor to display the same political courage he did as mayor of San Francisco, when he ordered the city to issue same-sex marriage licenses in 2004.

“He certainly can stop an execution,” Farrell said. “That’s within his power.”

The state Constitution gives the California governor the authority to “grant a reprieve, pardon, and commutation,” but those executive powers have limits.

For condemned inmates convicted of a single felony, Newsom has authority to commute sentences to life in prison. But the governor cannot commute the sentences of prisoners convicted of two separate felonies — a population that includes more than half the inmates on death row — without the approval of the California Supreme Court. The court rejected 10 commutations handed out by Gov. Brown in his last full month in office, all of which involved people convicted of multiple felonies. The court did not provide an explanation for the action.

The provision is in the Constitution to prevent an “abuse of power” by the governor, said Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the pro-death penalty Criminal Justice Legal Foundation. It was the first time in decades that California’s top court rejected a governor’s commutations, which should serve as a warning to Newsom, he said.

The governor also has the constitutional authority to grant reprieves to prisoners facing execution, in essence a temporary stay. Newsom could impose a de facto moratorium on capital punishment in California by granting a reprieve each time an inmate is sent to the death chamber, Scheidegger said. But those reprieves would expire as soon as Newsom leaves office, pushing the life-and-death decisions to his successor.

“That also would be an abuse of power. It’s not why we have clemency,” Scheidegger said, arguing that those powers should be used only as a protection against miscarriages of justice.

Shilpi Agarwal, a staff attorney with an expertise in criminal justice at the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, disagrees. She said the governor has the constitutional authority to commute sentences and prevent executions from taking place.

“The governor has very important role to play, and I sincerely hope that he chooses to exercise his discretion,” Agarwal said.

Governors in Oregon, Colorado and Pennsylvania have imposed moratoriums on executions in those states, all using executive powers similar to those held by Newsom.

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf halted capital punishment there in 2015 after deciding that the state had a “flawed system that has been proven to be an endless cycle of court proceedings as well as ineffective, unjust, and expensive.”

Newsom has voiced similar concerns, particularly regarding the racial and regional disparities related to who is sentenced to death in California.

Six former governors had urged Brown, who is opposed to the death penalty, to commute the sentences of all of California’s death row inmates before he left office in January, a request he rejected.

California voters approved a statewide ballot measure reinstating the death penalty in 1978, six years after it was halted by the U.S. Supreme Court and two years after a high court ruling allowed executions to resume. Since 1978, California has carried out 13 executions under Govs. Pete Wilson, Gray Davis and Schwarzenegger. During that same time, 26 inmates on death row have died by suicide, and 79 have died of natural causes, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Among the 24 death row inmates who have exhausted their appeals is Cooper, who was sentenced to death in 1985 after he was convicted of killing Doug and Peggy Ryen and their 10-year-old daughter, Jessica, as well 11-year-old Christopher Hughes, who was unrelated to the family. They were found stabbed to death in a Chino Hills home.

Newsom’s executive order requiring additional DNA testing in that case came after Cooper’s attorneys alleged that key pieces of evidence were not properly tested and needed to be analyzed with modern technology.

“As you saw what I just did with Cooper, I take this very seriously,” Newsom said. “I’ve been a strong advocate in opposition to the death penalty.”

Michael Morales, who was sentenced to death in 1981 for raping and murdering 17-year-old Lodi, Calif., high school student Terri Winchell, has also exhausted all of his appeals. His execution was stayed in February 2006 after his lawyers argued that the state’s lethal injection procedure using sedatives and paralytic agents might mask, rather than prevent, pain from the final heart-stopping chemicals.

A federal judge halted all executions later that year, ruling that California’s three-drug lethal injection protocol risked producing a painful death and violated the constitutional prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.

California finalized new lethal injection regulations in early 2018, which require executioners to use a single chemical, either pentobarbital or thiopental. But the administrative process the state used to determine those standards is being challenged in court by the ACLU.

Agarwal said she doesn’t expect the legal challenges against the death penalty to subside anytime soon. If true, Newsom may not have to decide how to handle the cases, just like his predecessor.

“I think that there is virtually no chance that California will be in any sort of position to begin executions within the next four years,” Agarwal said. “There’s just so many problems with the death penalty.”

Sacramento political scientist Kim Nalder said the close votes of the two death penalty ballot measures in 2016 showed that Californians are almost evenly divided on the issue, and the national trend has moved toward abolishing capital punishment.

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, eight states have abolished capital punishment either through the legislative process or by court ruling since 2007.

“Newsom might be on solid enough footing to do what he can to stall or stop executions if and when it comes to that,” Nalder said. “It could be a close call. You can always fall back as an elected official saying the voters voted for me because they trust my judgment.”

In August, Newsom told news outlet CALmatters that he wanted to give California voters “a chance to reconsider” whether to abolish the death penalty. But doing so could come with a drawback: If Californians again vote to keep the death penalty, Newsom might feel pressure to abide by their decision.

“Once you put it out to the voters it’s pretty hard to go against their will,” Nalder said.

Newsom, who is Catholic, said he has been doing a lot of “soul searching” in recent months. His late father, William Newsom, was also opposed to the death penalty, and the governor said they discussed the issue “ad nauseum.” In an interview with a University of California oral history project a decade ago, William Newsom, a former state appellate court justice, said he presided over three capital cases while he was a trial judge, and set aside the juries’ recommended death sentences in all of them.

Newsom said his father’s opposition was hardened later in life by the case of Pete Pianezzi, a longtime friend who was convicted of first-degree murder for shooting and killing a gambler and busboy in Los Angeles in 1937.

Pianezzi escaped the death penalty by a single vote and served 13 years in prison. He was later exonerated after mafia hit man Jimmy “The Weasel” Fratiano disclosed that the murders were committed by two gangsters with ties to a Los Angeles crime family.

Newsom led an effort to get Pianezzi a full pardon, which Brown granted in 1981.

“This is a deep issue personally for me, going back to my relationship with my father,” Newsom said. “A governor has to sign off — and you’ve got to live with yourself.”

Twitter: @philwillon

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.