Capital punishment in California exists in law, but in practicality ended in 2019 when Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered death row to be dismantled.

Still, 625 men and 20 women remain incarcerated with death sentences, facing the unlikely but possible prospect that under a different governor, they could be executed. About one-third of the condemned are Black.

In recent months, Santa Clara County Dist. Atty. Jeff Rosen, once a prosecutor who believed in capital punishment and one who rejects association with the progressive prosecutor movement, has been quietly preparing to ask courts to change the penalties of 14 men from his county who are waiting for that ultimate sentence to be carried out.

In most cases, he wants the court to re-sentence these men (Santa Clara has no women on death row) to serve life without parole. But in a few separate cases, already completed last year, he has requested that they be given the chance of freedom.

Why? An inherent racism in our justice system handed down from slavery to mass incarceration and capital punishment, he cites as a main reason.

“[W]e are not confident that these sentences were attained without racial bias,” his office wrote in a motion to courts expected to be filed in coming days in multiple cases. “We cannot defend these sentences, and we believe that implicit bias and structural racism played some role in the death sentence.”

For activists in the death penalty world, that’s an old argument. But coming from a mainstream prosecutor, it’s a mic drop.

Jill Harrison’s daughter Ciara was murdered in 2019. Now Harrison is trying to help the man who killed her child, fighting for Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan to change San Quentin.

Rosen’s unprecedented move (he is the only prosecutor in California to have made such a blanket request, and the only one I could find nationwide) has gone largely unnoticed. But it represents a new battleground in the fight over the death penalty.

While many prosecutors around the state and the nation have stopped the use of the death penalty moving forward, Rosen is the first to look back and answer the question — with collective action — If it isn’t fair now, how could it have been fair then?

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Rosen’s move to undo what he sees as the ongoing injustice of past convictions puts pressure on other prosecutors to follow suit, especially those such as George Gascón who have made their reputation as reformers but who have failed to go as far. Gascón’s office said he has been examining death penalty sentencing on a case-by-case basis and 29 people have been re-sentenced out of more than 120 on death row convicted in L.A. But he is unlikely to ask for a group re-sentencing in an election year, with a solid conservative challenger.

“It doesn’t mean that I think things are as bad today as they were 50 years ago, I completely reject that idea,” Rosen told me. “But I also trusted that as a society, we could ensure the fundamental fairness of the legal process for all people. With every exoneration, with every story of racial injustice, it becomes clear to me that this is not the world we live in.”

Elisabeth Semel, director of the Death Penalty Clinic at UC Berkeley, calls Rosen’s move “highly significant” because it examines every case in his jurisdiction, and has the potential to convince others that it isn’t just single cases that require examination, but the death sentence as a whole — a position the Legislature’s Committee on Revision of the Penal Code recommended in 2021.

Currently, about 35% of those on death row are Black, despite Black people making up only about 7% of California’s population. An additional 26% of death row inmates are Hispanic or Mexican. Overall, nearly 70% of death row inmates are people of color.

Semel points out that it’s not just the race of the alleged perpetrator that can lead to the death penalty, but also the race of the victim and the attitudes of those in charge of the prosecution. Suspects accused of killing a white person, for example, are more likely to face the death penalty than those accused of killing a person of color.

“There is nothing, nothing that these cases have more in common than racial discrimination, whether we are talking about privileging white victims, meaning seeking the death penalty in white crime, or disadvantaging Black clients,” she said.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The inherent unfairness of the death penalty, whether because of race or its finality, has been debated for years, often with soul-searching arguments that go beyond politics. Illinois Gov. George Ryan, a Republican, in 2003 issued a blanket commutation for all 167 inmates facing the death penalty in his state, citing worry that “the demon of error” was ever-present — one of the first and boldest actions by a prominent politician against the death penalty.

Former Oregon Gov. Kate Brown, a Democrat, did the same in 2022, re-sentencing 17 death row prisoners to life without parole. Twenty-three states, including Oregon, Colorado and New Mexico, have abolished the death penalty.

But California politicians, and voters, have been less certain. Over the years, voters have decided to keep the death penalty when asked via ballot measures. Rosen has asked for it four times, and won capital punishment in one case — that of defendant Melvin Forte, convicted of sexually assaulting and murdering a young German tourist. Forte’s sentence is among those Rosen is seeking to change.

Newsom, despite his moratorium, hasn’t gone as far as Brown or Ryan. That leaves the death penalty in California largely in the hands of locally elected prosecutors such as Rosen who have virtually no political incentive to revisit past capital convictions.

I am not one to easily believe politicians, but when I asked Rosen why he was putting himself out front on a controversial issue, he told me it was because it was the right thing to do. Then he told me how he came to that conclusion, and it feels genuine because I experienced something similar myself.

Rosen’s views on the death penalty had been shifting since the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Shortly after, he put into place a series of prosecutorial reforms meant to address racial bias, including deciding not to seek the death penalty in future cases.

But it wasn’t until two trips to Montgomery, Ala. — once the capital of the Confederacy and now home to the Legacy Museum, which traces the history of slavery through mass incarceration of people of color — that the past took on relevance for him as a matter of contemporary justice.

How can a museum have such an impact? I went myself because I couldn’t quite imagine. A modern monument in what can only be described as a dismal city where the ghosts of millions of trafficked humans seem ever present, the museum lays out with astonishing clarity a history that is painful, but necessary to acknowledge.

Twelve million Black people kidnapped from their homes overseas and sold at American auctions.

Nine million Black Americans subjected to the domestic terror of Jim Crow-era violence that left justice in the hands of racist vigilantes. The museum documents the lynching of a 3-year-old girl, along with her 10-year-old sister — just two of dozens of children killed, often while law enforcement watched.

That violence forced many to move to the North and West to avoid murders, rapes and beatings. But even in those supposed safe havens, including California, 10 million Black Americans found that, just like in the South, they were segregated into lesser housing and lesser schools, and ultimately had lesser opportunity.

Banks wouldn’t lend, police used crimes such as jaywalking to arrest, schools failed to teach. And beyond that secretive repression, they were still not immune to the violence of the slave states — California may have lynched at least 350 people between 1850 and 1935.

That segregation and bias led to 8 million Black Americans systemically over-incarcerated though laws and policies that targeted people of color, and communities of color, turning vigilante justice into legal imprisonment.

At the Legacy Museum’s sister site, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the weight of that oppression and pain takes on literal significance. Rectangular steel markers, their shape like a coffin hanging from a limb, serve as monuments to 4,400 Black Americans lynched between 1877 and 1950.

The markers begin at eye level, but walking down from the hilltop site, they begin to hang over visitors, casting long, cold shadows.

It is impossible to pass beneath them and not feel their historical weight.

“I think that if more people went there, they would think a little differently about our country, and hopefully act a little differently also,” Rosen told me.

“I went there supporting the death penalty,” he said. “I left not so sure anymore.”

Though I was less certain about the death penalty before visiting Montgomery, I came away, like Rosen, with no doubts that its origin is dark and tainted.

Rosen said the realization that was most profound for him was how often supposedly illegal lynchings took place with the support of law enforcement — too often victims were handed over by deputies or killed on the courthouse steps.

“If not considered lawful exercises of state power, they weren’t unlawful,” Rosen pointed out. “Nobody was prosecuted for them.”

It was not until well into the 20th century that outcry over that semi-state sanctioned murder made it untenable even in the South. The answer to that outrage was to move the killing back inside the courthouse, with the use of the death penalty.

California plans to remake San Quentin as a new kind of prison, modeled after Scandinavian ideals that value rehabilitation over punishment. An L.A. re-entry facility has already made the change.

Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Legacy Museum and a death penalty lawyer, calls Rosen’s decision “remarkable” because it takes that true but sidelined history and turns it into mainstream policy.

“It says something about our ability to confront history honestly and to turn the page in a meaningful way,” Stevenson told me. “Some people may not understand it, some people may have issues with it. But the truth is that we can create a future that allows us to begin to experience something that feels more like freedom, more like equality and more like justice than we’ve ever experienced in this country.”

A devout Jew, Rosen said the museum and his own experiences as a prosecutor made him question if the death penalty can truly be separated from that foundation of lynchings — and if killing as punishment can ever be just or come from a place of moral authority regardless of race.

“It’s not like I open the Bible and the penal code and figure out what to do,” he said. “I think that in my lifetime, we will look back and say it was not right to execute people.”

Rosen’s office has reached out to all the victims in the cases he is examining. Some are relieved to have finality in the case, he said, knowing the death penalty is really just a never-ending appeal. Some would prefer to keep the death sentence regardless of whether it takes place or not.

Some have simply moved on after so many years and are open to his argument that there should be limits to human justice. Rosen tells them he wants his power, and ours, to end at deciding where people who commit the worst of the worst crimes die — in prison.

Not when.

He makes no excuses for horrific crimes that led to the death sentences in his jurisdiction. A grandmother stabbed to death. A wife shot and rolled down a hill, still alive. A gas station attendant killed to prevent his testimony about a robbery.

But he points out that many of the crimes that led to the death penalty decades ago would not have garnered the same punishment today. Some of the perpetrators were convicted as teenagers, some were accessories to the crime at a time when laws made fewer distinctions. Many have been imprisoned for more than 30 years. Some had unfair trials.

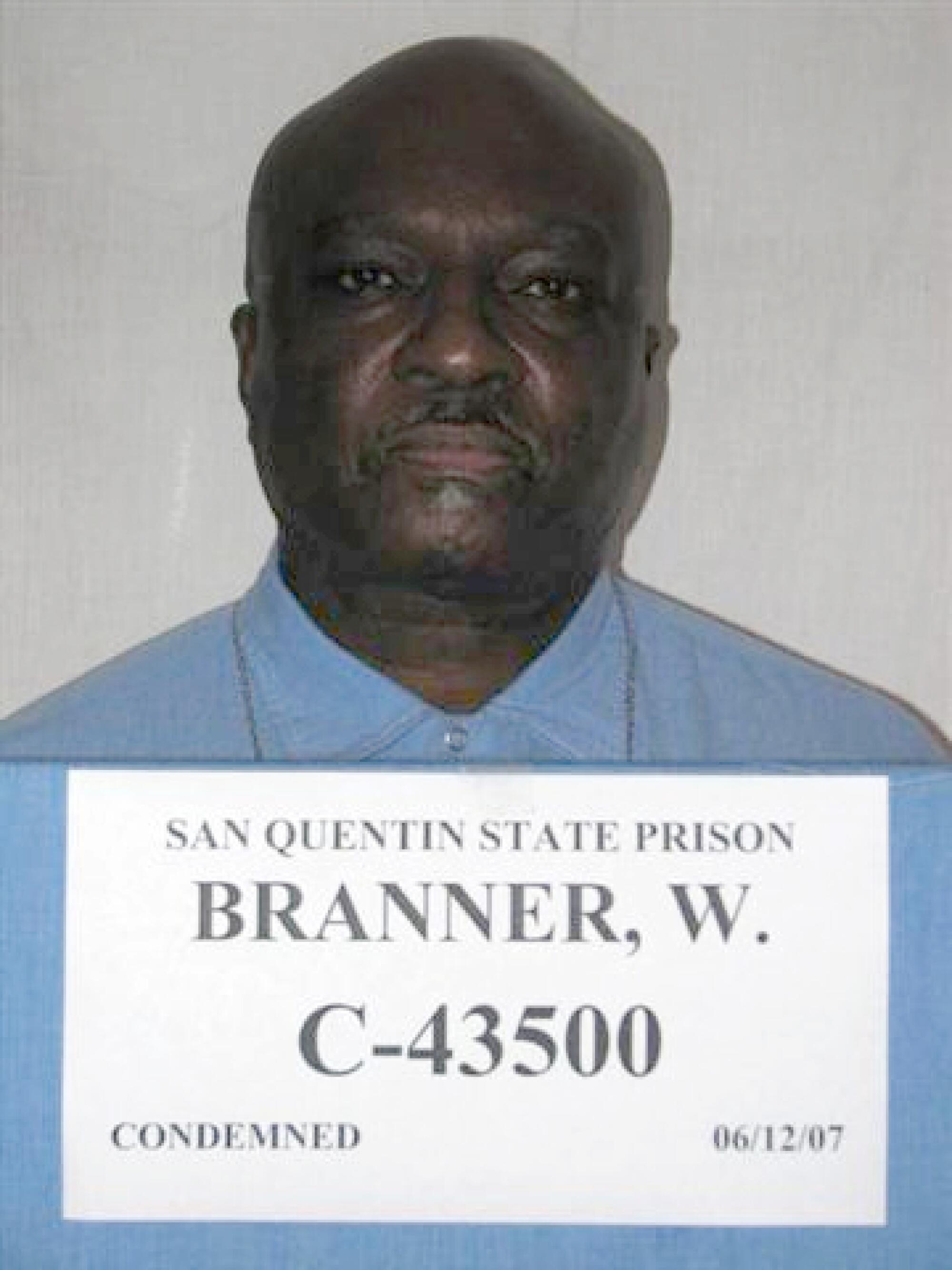

One of those men is Willie Branner, a Black man who was convicted in 1982 by an all-white jury of shooting and killing jewelry store owner Edward Dukor during a robbery in Milpitas. The prosecutor in that case removed Black, Asian and Jewish jurors, including removing one female Black juror in part for being “overweight and poorly groomed.”

Recently, a federal court ruled that Branner was entitled to a new trial based on that less-than-impartial jury.

Now 74, Branner has been, as they say, a model prisoner. I messaged with him recently, and he told me he is relieved that his family no longer has to worry about him someday being executed. He dreams of possible freedom, opening a tailoring business and working to “help rebuild our society for the rest of my life, God willing.”

Branner does not know how his sentence will work out, only that it will not end with death. He is not claiming he is innocent, just that he has changed in the decades since the shooting, just as Rosen has changed since he first began prosecuting.

“It’s not that I think that the people on death row in my county have not committed horrible, terrible crimes. They have,” Rosen said.

There is no doubt, he believes, that decency and public safety demand people be held accountable for their harms.

Even when that means holding ourselves accountable for ours.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.