What families of murder victims have to say about Gavin Newsom’s death penalty ban

Reporting from Sacramento — Cindy Rael was home Wednesday morning watching television when the news turned personal — Gov. Gavin Newsom was halting executions in California, including for the man who killed her daughter Brandi eight years ago, shooting her and lighting her body on fire in front of her children.

“I said, ‘Are you kidding me?’ I was shocked and angry,” said Rael. “I have to live with this every day of my life…. There is one question I would like to ask the governor: What if it was his daughter who was brutally murdered?”

Five hundred miles north, another mother, Aba Gayle, had made the trip to Sacramento from northern Oregon to meet with the governor. She said she felt grateful for his decision.

“What I say is, ‘Don’t murder someone in my name,’ it does nothing to benefit my daughter, it won’t bring anybody back,” said Gayle. After years of living in rage and pain, she befriended the death row inmate who killed 19-year-old Catherine Blount in September 1980 at a home north of Auburn.

As word of Newsom’s moratorium on the death penalty spread, victims’ families reacted with varied emotions. Most have lived through grief, legal trials and long waits after the murder of loved ones, and their responses were a reminder of how personal and polarizing the issue has remained through the years.

The previous governor, state lawmakers and a growing network of civil rights and criminal justice reform groups in California have worked to fundamentally change how the state deals with offenders in recent years. But the plight of inmates on death row has garnered scant sympathy with voters, who in 2016 narrowly rejected a measure that would have halted executions in the state and passed one meant to speed them up.

While Newsom and reform advocates argue that the death penalty is weighted with racial and other biases and has not been fairly applied, those in favor contend it is just punishment for the worst crimes. It is also one voters said they want.

“California just became a dictatorship today,” said Tami Alexander, wife of former NFL player Kermit Alexander. Both are vocal proponents of the effort to fast-track the death penalty. “It is not about the process, about democracy, the journey, a vote.”

The couple has waited more than three decades for the execution of Tiequon Cox, who shot and killed her husband’s mother, sister and two nephews in South Los Angeles in 1984. Her husband could not even begin to comprehend the governor’s decision, she said, adding that she felt for the families of victims like Marc Klaas, whose daughter Polly was kidnapped and strangled by a man who flipped the father off in court.

“I feel for the family of [Riverside Police Officer] Ryan Bonaminio who, as Earl Ellis Green holds a revolver to his head, begs for his life,” Tami Alexander said. “What would Gov. Newsom say to his dad today? That God will take of it. No, we need our governor to take care of it.”

For many families of victims, the issues around executions are often less lofty than politics or philosophical stands. Rael said her grandchildren have struggled to overcome their mother’s killing and it makes her angry. On the night it happened, a fire alarm awakened four of her six kids. When they came into the hallway, they saw their mom’s body on fire and attempted to put it out with cups of water rushed from the kitchen.

“He didn’t just take a life, he ruined a bunch of lives,” said Rael of Tyrone Harts, an ex-boyfriend of Brandi Morales-Rael. Harts was sentenced in 2015 and is now on death row at San Quentin.

“I never really thought about it the way I do now, but it happened to me, it happened to my oldest child,” said Rael. “If I could have taken [the execution] in my own hands, I would have.”

Rael said she believes in biblical justice, “an eye for an eye.” But a different take on faith is also at the core for many of those against executions.

“I am very pleased that Gov. Newsom is following his conscience on this issue and I agree with what his beliefs are,” said Amanda Wilcox, whose daughter Laura was killed by a gunman in 2001 while working a temporary job in a mental health clinic in Northern California. While her daughter’s killer was sent to a mental hospital, she has been an advocate of halting the death penalty and met with Newsom this week.

“I felt a violent act is what created this problem in the first place and to respond with more violence doesn’t help,” said Wilcox.

On Wednesday, Newsom said he talked with victims at different ends of the spectrum and did not make his decision lightly. After the announcement, he met with family members of victims like Beth Webb, who lost her sister and several friends in a 2011 mass shooting at a Seal Beach hair salon.

“He looked touched, he looked emotional and vulnerable,” said Webb, who became a vocal critic of the criminal justice system after the case against her sister’s shooter dissolved in a scandal over the use of jailhouse informants. It should have been an easy conviction to secure: The gunman admitted to the crime and was caught with weapons near the scene. Her mother, who also had been shot at the salon, saw him pull the trigger.

Webb has since become a board member of the nonprofit Death Penalty Focus to abolish executions. She has a photo of her sister tattooed on her arm. It’s of Laura on her wedding day, four months before she was killed.

“These are tough things to square, these are hard things to process,” Newsom said earlier. “And for the grace of God go any of us. And to the victims, all I can say is we owe you and we need to do more and do better, more broadly for victims in this state. That was one thing that came home to me in a very deep and impactful way. But we cannot advance the death penalty in an effort to soften the blow of what happened.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s opposition to the death penalty appears destined for a test »

As public opinion of the death penalty has dropped over the years, hitting a record low in four decades in 2016, according to a Pew Research Center study, evidence has mounted that the current system is broken, expensive and fails to deter crime. But researchers say neither side of the debate has invested enough time or resources to study the effect of executions on victims’ families.

The limited research that does exist shows a slow death penalty system can harm families attempting to heal. One of the most recent analyses, a 2012 report in the Marquette Law Review, found better levels of physical, psychological, and behavioral health among crime survivors of adjudicated cases in Minnesota, a life-without-parole state, over those in Texas, a death penalty state where cases often became mired in lengthy appeals.

Outside the Capitol, Gayle said a prosecutor promised her the conviction and death sentence of Douglas Mickey would bring her closure. But after the trial was over, she struggled to find peace for eight years until the right people came into her life, the right books fell in her hands. She joined the Unity Church and Church of Religious Science, she said.

“‘You must forgive him and you must let him know,’” Gayle said, recalling the words of an inner voice she first heard one day in the spring of 1992. She brushed it off at first but it became so loud, clear and persistent that she found herself penning a letter to Mickey near dawn.

“That letter did not come from my intellect, it came from my heart,” she said.

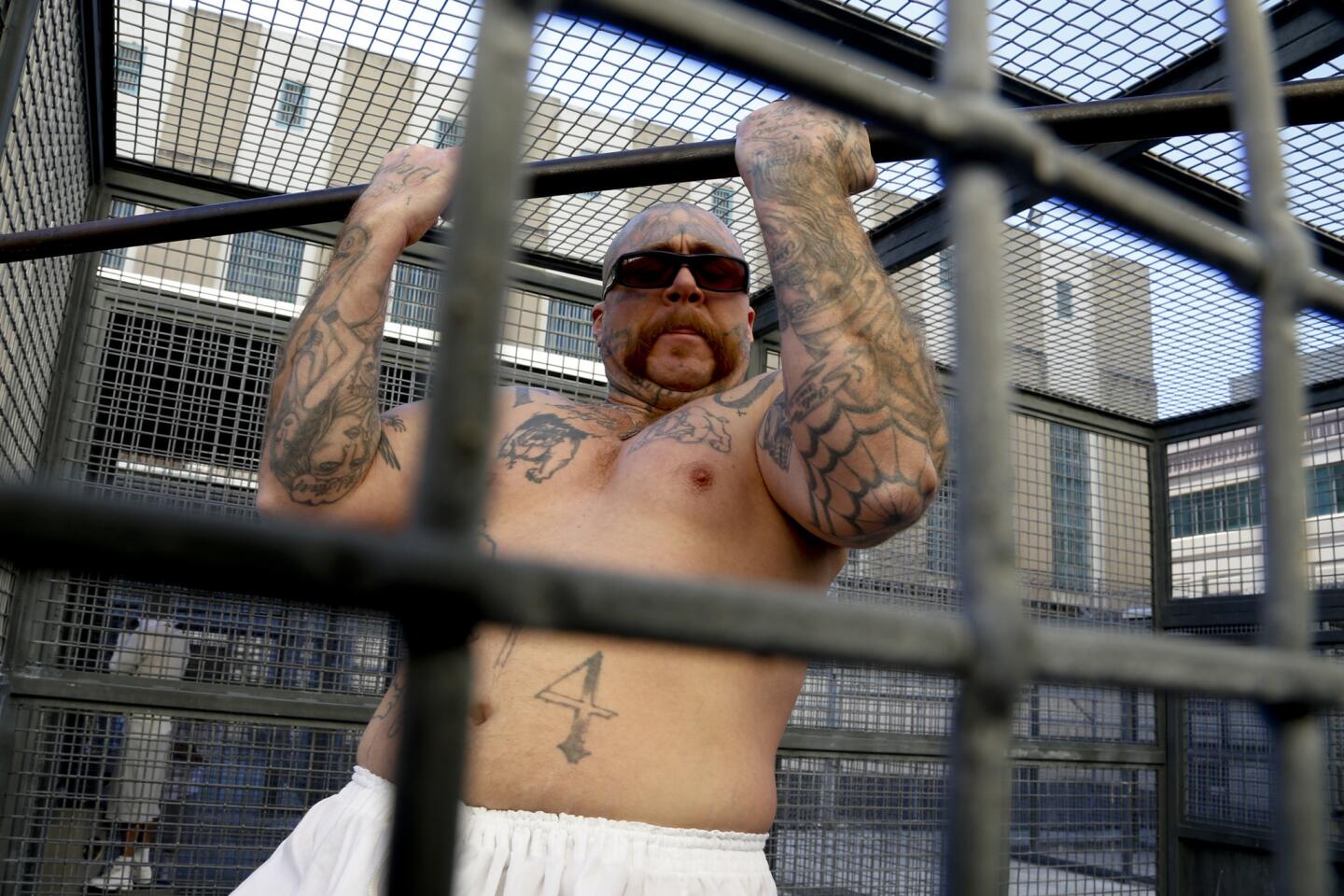

It took her weeks to build the strength to put it in the mail, she said, but she did. Soon afterward, she met him at San Quentin death row and realized he was not a monster and that his life would never be the same. If executions had resumed in California, he would have been sixth in line to die, Gayle said.

“Ending executions,” she said. “That has become the focus of my life, regardless of whether it happens in my life.”

Despite the varied views on Newsom’s action, families of victims shared Gayle’s sense that resolution was personal, and beyond the ability of courts to provide. For many, what happens to the perpetrators by necessity takes second stage to the daily tasks of coping.

“This idea of justice and closure, there is no such thing,” said Wilcox. “No matter what happens to the death penalty, I don’t get Laura back.”

More coverage of California poitics »

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.