The violence of rural life blends with the gravity of Chinese myth in the horror novel ‘Sacrificial Animals’

Book Review

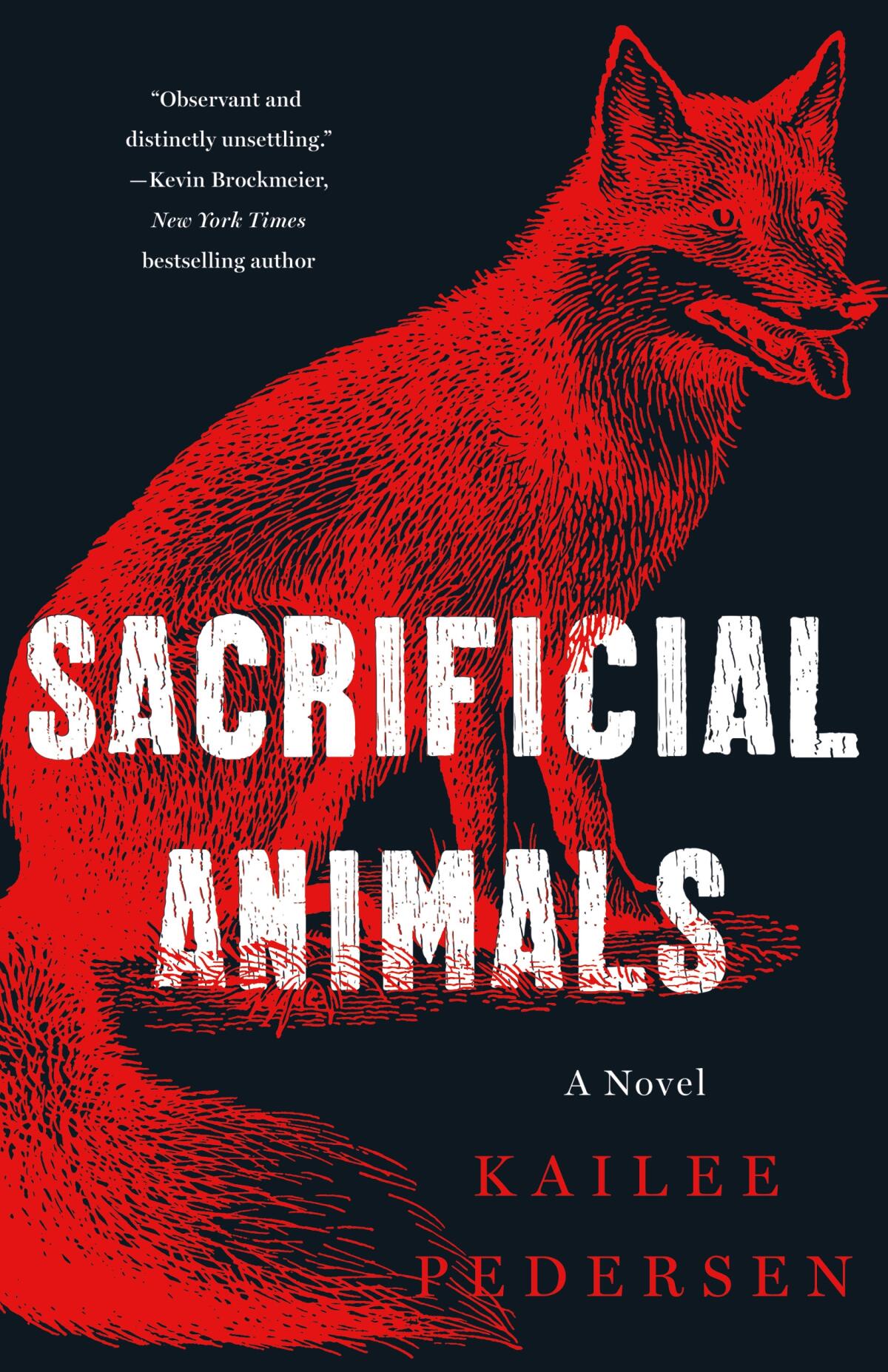

Sacrificial Animals: A Novel

By Kailee Pedersen

St. Martin’s Press: 320 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

It doesn’t take long for things to get dark in Kailee Pedersen’s debut horror novel, “Sacrificial Animals.” Dark and bone-chillingly bloody. The author pens a macabre hymn to violence, drawing inspiration from a variety of literary and mythological sources.

Early on, Pedersen writes in the tradition of a frontier “King Lear”: two sons vying for a petulant father’s affection and inheritance while he rages against the world. Think “Yellowstone,” but meaner, with a “glass-eyed buck’s head” guarding the gate. Jane Smiley fans, beware: Pedersen shows no mercy on these thousand acres, leaning into disturbing details and gore.

“Sacrificial Animals” begins at Stag’s Crossing, the expansive farm of Carlyle Morrow, a barbarous widower patriarch who rules the land, a herd of trap-mouthed greyhounds, his emotions and his two teenage sons with all the subtlety of an axe. In the opening pages of the story, Carlyle tears his boys out of bed in the middle of the night to hunt a mother fox who’s gotten into the chickens. He metes out his retribution upon her young in a heartless scene of cruelty and “wild omophagia,” forcing his sons’ complicity in their deaths in an attempt to impart his own cold inhumanity to the next generation.

In chapters alternating “Then” and “Now” Pedersen follows Carlyle’s tender youngest son, Nick, as he realizes he’ll never live up to his father’s rough ideal. Carlyle’s violence is “keen and beautiful as the silver curve of the fishhook. Nick gentler and perhaps even fawn-like, strange somehow. Fashioned in the image of his mother,” who died in childbirth along with a third brother. Joshua, the eldest son, is testosterone embodied, the favorite.

In the short stories of ‘Highway Thirteen’ that span almost 80 years, Fiona McFarlane explores the lives of people affected by a spree of killings in Australia.

When Nick recognizes he cannot survive at Stag’s Crossing, he leaves to nurture his burgeoning queer identity and build a life in books, applying “his vicious and mangling intelligence to literary criticism” rather than the hunt. The favorite, too, falls out of their father’s favor early when Joshua marries Emilia, a woman of Asian descent, despite the patriarch’s racism and suspicion of outsiders. No one is safe from Carlyle’s legacy of malice, and he finds himself alone.

Adult Nick reckons with the brutality of his childhood as much as he is able and puts a lot of distance between himself and Carlyle. He forgets what he can, but the acute pain of his father’s tyrannical rule remains. When Carlyle calls to say he’s dying of cancer, Nick is forced to go back home and address his unhealed wounds. He also has to bridge the distance between himself and his long-estranged brother, who returns as well, along with his wife, who immediately sets about needling Nick.

Throughout, Pedersen maintains a sense of doom, building suspense and expectation by reminding us that neither son fully escaped the meanness their father wanted to breed into them or the imperative to come back home. “Like dogs they will come when they are called, the Morrow boys,” Pedersen writes, dehumanizing the sons in a repeated comparison.

The genre-hopping author’s latest work is a literary thriller about love gone sour in Lagos, Nigeria.

Pedersen is ruthless. It’s not a matter of whether the story will end in death, but when, whose and just how extensive the devastation will be. Pedersen leads her characters and her readers menacingly toward oblivion. And in addition to its savagery, “Sacrificial Animals” is a Shakespearean tragedy: people control fate and each other; sons try to rebel against their father and their destinies. Pedersen weaves eerie sentences together from archaic language, and the novel builds with a gruesome, anxious energy as the author reveals its connection to Chinese mythology.

While fraternal jealousy, generational pain and malice rule the narrative, she also integrates elements of the supernatural. Nick is not just sensitive but also “sometimes has premonitions, headaches, the pains of a seer.” Closeness with others reveals Nick’s ability to see into their past, experiencing their memories. This becomes especially important as he seeks to define himself in early adulthood, yet his father and the farm present a few blind spots. The reader knows more than he does, and we wonder how long it will take him to figure out the dark secret. Pedersen’s story raises questions of human and animal cruelty and implores us to look beyond assumptions of what a soul can be. Identity is mutable. Sins are generational.

As the book builds to its end, Pedersen’s story slips the bounds of reality entirely, surrendering to the fantastical and its mythological undercurrent. The novel’s final pages are a wild frenzy of beauty, vengeance and viscera. A buffet of offal. A stinking mass of rotting innards slipping from a gaping wound. Is that too vague? It’s intentional. There’s a mystery at the heart of this story that parallels the recurring motif of the fox hunt, and I don’t want to spoil it. It’s Nick’s slow realization of the depths of his complicity in his father’s violence that produces the final gut punch.

Pedersen’s grisly tale joins many distinct threads together into a terrifying end. “Sacrificial Animals” is remarkable in its keen barbarism, the author’s blending of the ordinary violence of rural life with the gravity of a Chinese myth. Her characters live “only for the ferocious hunt, the glorious betrayal. The suffering of others is its own delicacy,” she writes — “more pleasurable than that of even raw flesh.”

Heather Scott Partington is a teacher in Elk Grove and president of the National Book Critics Circle.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.