When Zoë Bossiere was a child, their family moved from the D.C. suburbs in Virginia to Cactus Country, an RV park in Tucson populated by drifters, off-the-grid families and a host of creepy and enchanting desert creatures. In that wide-open landscape, Bossiere also began working through their gender identity, shifting from the girl they were raised to the boy they aspired to become. “I associated boyhood with cool-headed stoicism, rugged self-reliance, the freedom to live on my own terms,” Bossier writes in “Cactus Country,” their bracing memoir about the experience.

In this interview, edited for space and clarity, Bossiere speaks from their home in Cannon Beach, Ore., about writing the book, the connection between boyhood and desert landscapes, and the book’s arrival amid attacks on LGBTQ+ youth.

Ah, summer. The time of year when school lets out, days grow long and grills fire up. Even in places like L.A., though, where rain can be scarce, there are plenty of reasons (too hot, too lazy, too sunburned) to stay inside and curl up with some AC. That’s where The Times’ 2024 Summer Preview comes in: As you check out our guides to the movies, TV shows and books we’re looking forward to this season, be sure to read the stories below about some of the most highly anticipated.

What inspired you to write about growing up in the Southwest?

It wasn’t until I left to go to grad school in Oregon and then Ohio that I realized how much Tucson shaped me. In these institutions, there was great pressure to be a certain kind of academic, to be from a certain kind of background. I had grown up in a trailer, and I had this incredibly gender-expansive childhood, but I found that when it came up in conversation it was kind of a curiosity, something that a lot of people hadn’t experienced. So I was trying not to talk very much about Tucson because I felt that if I delved too deeply into that, perhaps I wouldn’t succeed in these places.

I began to feel really alone, like there weren’t very many people who could relate to the experiences that I’d had. I also was having a hard time understanding what my paths meant about the kind of person I am now. So it made sense to start thinking about, “What does it mean that I had this type of childhood?”

On the Shelf

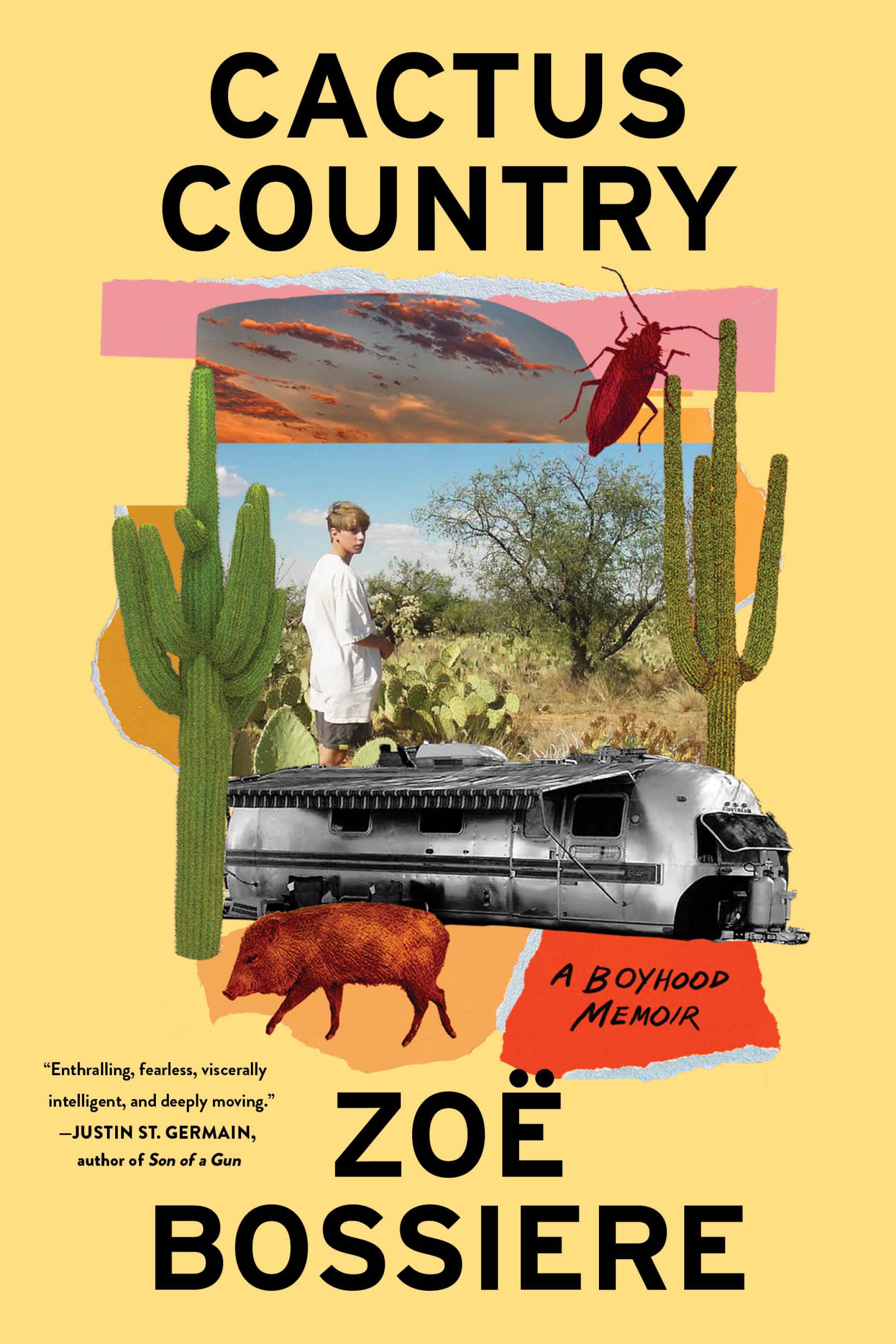

Cactus Country: A Boyhood Memoir

By Zoë Bossiere

Abrams: 272 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

How did you get into telling the story?

I started writing about what I knew intimately, and that was the desert, the plants and the heat. It’s like another planet. There are animals that are really sharp and stoic, that bite and sting. Then I started writing about the boys and men who populated the landscape, and I started to realize how much these boys and men were like the landscape. They were also sharp and stoic. I then began to access the boy that I had been living among them and tried to find my place there.

Those desert creatures seemed to be particularly inspirational.

Each animal in the book is in some way representative of something I was going through at the time I encountered them. Palo verde beetles are enormous — as a child they were larger than my hand. And they look like monstrosities, but they’re so gentle. They don’t typically fly away from you. You can pick them up. They won’t pinch you. But at that time, I was trying very hard to determine what it meant not only to look like a boy but to behave like a boy. Part of that was destroying these beetles — seeing them as a kind of threat even though they were benevolent.

Lucy Sante chronicles her gender transition in her arresting memoir, ‘I Heard Her Call My Name.’

Did growing up in Tucson make coming to terms with your gender easier than if you’d stayed in Virginia?

Tucson was integral. In Virginia, I went to a lovely little school and I had a lot of friends. But everybody there knew me as this little girl, and I was becoming more and more discontented with my public identity as a girl. My parents sold Tucson to me as a fresh start: “In Tucson you can be whoever you want to be.” I took them at their word. What I wanted to be in my heart more than anything in the world was a boy. I got a bowl haircut and everybody saw me as a boy. I wasn’t questioned. It was assumed that I was a boy.

You don’t talk about your parents in the book as much as the friends and creatures surrounding you.

In Cactus Country, there was this division of worlds between the children and the adults. We were on our own all day, outside in the desert. Much of my lived experience in childhood there revolved around the kids I was playing with, or the neighbors I was spending time with. There’s a chapter called “Javelina Sunset,” which is about javelinas coming into the park looking for food. All of us kids were really excited because we saw them as mythical creatures that were beastly and scary and dangerous. But javelinas are pretty mild. The difference in the ways we kids talked about the javelinas and the way my parents and neighbors did was worlds away. I tried to maintain that distance throughout the book.

Diana Goetsch spent months visiting red-state libraries to do presentations on the freedom to read. Would she be recognized, or clocked as transgender?

You write about how the internet was a saving grace for you to work through your gender identity, but that you had few other options. Are there books that you can think of now, where you think, “If only I had that in my hands it would’ve helped?”

I did find Kate Bornstein’s “My Gender Workbook,” which I read so many times that the cover fell apart and the spine came undone. But I also remember feeling — because I was probably 15 when I first read the book — that a lot of the questions or themes of the book were more oriented towards adults. It was talking about how to navigate a career, how to navigate your sex life, things I wasn’t actively thinking about at that time. I remember thinking, I wish there was a version of this book for when I was 14, 15. Today, there are many versions of that book or similar types of books. It’s exciting to be able to contribute something to this growing body of literature.

Imogen Binnie’s ‘Nevada,’ first published in 2013, follows two people at different points of a transgender journey, each trying to live in the present.

You write about your experience in school with bullying and misgendering. What would have made that experience more positive and safer for you? How can we address it now?

We have specialists in affirmation of trans kids, which is a positive. But I think about Nex Benedict [a nonbinary Arkansas 16-year-old who committed suicide in February after sustained bullying] and what happened to them, which is just horrific, horrific.

I would say the thing that we need the most, whether it’s a teacher or a doctor or anyone who is in charge of the care and protection of trans children, is to not acquiesce. I really think that it’s going to take a lot more than just affirming trans kids at this point to prevent deaths, to prevent what happened to Nex from happening to the next kid. We need to resist because that is the way that every civil rights movement has gone. We won’t get anywhere if we continue to fall in line and every time there’s a rights violation coded into law, we abide by it. I just don’t think that’s the path forward. I don’t think that we make progress that way.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.