Review: A shatteringly honest novel of trans identity gets a supremely timely reissue

On the Shelf

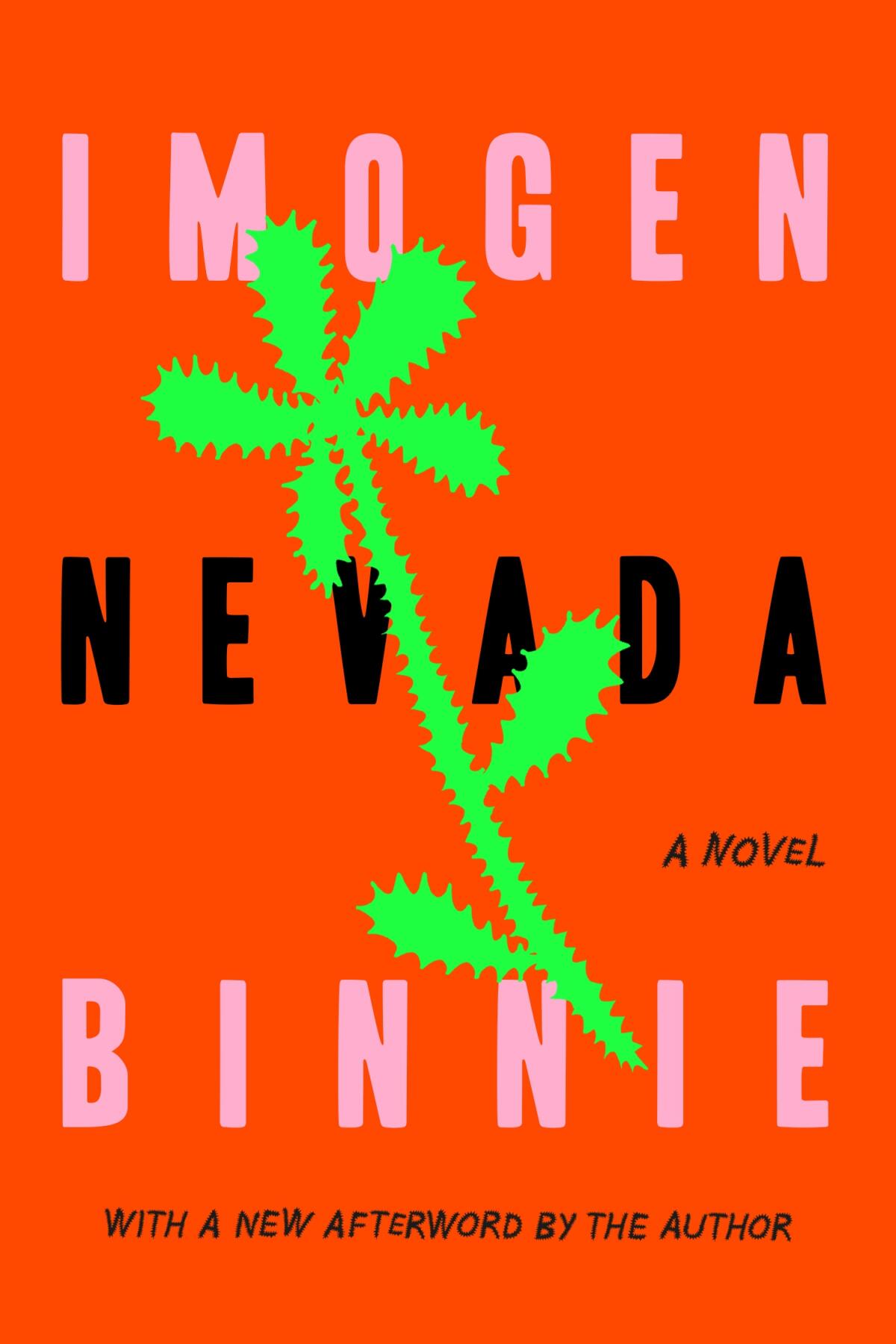

Nevada

By Imogen Binnie

MCD X FSG: 288 pages, $17

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The popular discourse around transgender people focuses on fears of narrative disruption. Trans identity is often presented by today’s reactionaries as a kind of contagion that infects the young, preventing boys and girls from fulfilling their natural destiny as men and women. Children are supposed to have the future waiting inside them; transness breaks the normal progress of time.

Imogen Binnie’s groundbreaking novel “Nevada” challenges this kind of transphobic determinism. First released in 2013 by Topside Press and reissued this week by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, it’s a road-trip novel that refuses to go anywhere, in which people aren’t locked into linear narratives. Life stories pool in stasis or loop around on themselves. The challenge for Binnie’s characters is to be in the moment, not to reach some foreordained gendered goal.

The novel is split into two nearly equal halves. In the first, Maria Griffiths, a 29-year-old trans woman, watches her life in New York City fall apart. Her relationship with her girlfriend disintegrates and she’s fired from her crappy bookstore job. She decides to drive out West, which takes her into the novel’s second half.

Stopping in the tiny town of Star City, Nev., she meets James, a 20-year-old in a dead-end job at Walmart who is struggling silently and desperately with his gender identity. Maria and James both think she can help him — though things don’t resolve quite so neatly.

In a new afterword for this edition, Binnie explains that she was tired of the way that transition, the “mysterious in-between phase,” was presented as “the most salaciously interesting thing to people who don’t have to go through it.” So instead of retelling the usual trans narrative of discovery, change and arrival, she decided to excise the middle.

A social comedy on ‘detransitioning’ asks: Who is anyone to judge?

Maria is many years post-transition; James hasn’t yet begun his. But Maria’s story isn’t over and James’ is already underway. They aren’t part of the one story we are told almost exclusively about trans people — the one fixated on the change.

The fact that Maria and James exist outside that story isn’t just a problem for cis people. It’s a problem for the main characters as well. The weight of who they are supposed to have been or who they are supposed to eventually be cuts them off from their life right now, the one they’re trying to live in.

When Maria’s girlfriend tells her she’s cheated on her, Maria can barely respond because she’s stuck in the emotional loop of past trauma. “Hey, you stupid boy-looking girl, why aren’t you having any feelings?” she asks herself. The answer she comes up with is that “I learned to police myself pretty fiercely” as a child, trying to hide her true desires and true self from everyone around her. The present is congealed in the past.

James has the same — or perhaps the inverse — problem: It’s the future that paralyzes him. His girlfriend Nicole is frustrated because he never tells her what he wants. He can’t even tell her which movie he’d like to watch.

That’s because he’s terrified of where his desires might take him. If he admits he doesn’t want to see a lousy Drew Carey movie, he’d have to admit he wanted to watch “Paris Is Burning” or “Transamerica.” “The whole castle would tumble down and it would lead to being honest about what kind of clothes he wants and what kind of body he’d want to have so he could look okay in those clothes.” The narrative insistence that any step forward is every step forward freezes him in place.

Our regularly updating 2022 Pride guide to culture will feature novels and memoirs from LGBTQ icons, must-see TV series, music, movies and much more.

If trans life is indeed a deterministic narrative, then Maria and James are the same person at different points on the timeline. Both sense this as soon as they meet. “You kind of looked exactly like me when I was twenty,” Maria tells James, “and I was like, I wish I had had somebody to talk to about this stuff when I was that age, instead of just the stupid 2002 internet?” The trans narrative almost begins to take on sci-fi overtones. Maria is James’ future self time-traveling to tell him what he should be and where he should go. James is Maria’s past self; she can fix herself by fixing him before he becomes her.

None of that works though. Maria and James aren’t the same person, and there’s no one narrative for being trans — or for being anyone.

Jack Halberstam has argued that trans people’s lives exist in a “queer time”; they don’t follow straight developmental paths or hit straight milestones in a sequential progression. Or, as Maria puts it when she worries she’s too old to change her life, “rejecting normative ideas about age is as hard as rejecting normative ideas about gender.” You’re never too old or too young to experience catharsis, or to be yourself.

Maria and James both earn moments that look like catharsis before it slips away, as catharsis tends to do. The narrative doesn’t resolve; neither the past nor the future is fixed. But Binnie’s love of her characters, of their confusion, of their insights and of their language produces its own catharsis of sorts.

Here and now, the novel makes as much sense (if not more) as it did nine years ago when it was first published. In the middle of a trans panic, with transphobes demanding that love, work, achievement and gender all follow the same cis narrative timetable, “Nevada” steals a car, walks off the job and drives someplace else.

Berlatsky is a freelance writer in Chicago.

Now Florida Gov. DeSantis wants to strip medical care from transgender children and adults.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.