Editorial: Climate change is making more California homes dangerously hot. It’s time state laws caught up

Whether you rent or own in California, your home is required to have a functional heating system capable of keeping temperatures at least 70 degrees.

But there is no requirement for cooling equipment to keep your home from becoming dangerously hot. Landlords have no obligation to provide air conditioners, swamp coolers or anything to keep rental units safe for occupants during heat waves.

That might have been understandable decades ago. But it’s unacceptable now that greenhouse gas pollution has driven average temperatures more than two degrees higher than they were in the 1950s, fueling more frequent, dangerous and record-breaking heat waves and a mounting death toll.

How can city officials help save lives during heat waves? Make cooling a requirement for habitation, like it is already is for heating during cold weather.

Cities and counties across the country, including Houston, Dallas, Phoenix, Portland, Ore. and Clark County, Nev., have already established indoor temperature limits or cooling requirements of some kind. Countries, including the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan, have them too. L.A. County is developing its own maximum temperature standards for rental units.

But California’s policies haven’t been changed to reflect our new reality.

In 2022 lawmakers failed to advance legislation to establish maximum indoor temperature standards for residential units. Instead they passed watered-down language that directed the Department of Housing and Community Development to come up with recommendations for maximum indoor air temperatures that ensure homes are safe for residents and submit them to the Legislature by the end of this year.

Earlier this month, the department released a disappointingly narrow draft of its recommendations, which suggest a maximum safe indoor air temperature of 82 degrees — but only for newly constructed residential units. While it would apply to rentals and owner-occupied homes, it would exclude more than 14 million existing dwelling units, where the vast majority of Californians live, millions of them without air conditioning. That standard is weaker than a previous draft, in April, that proposed the adoption of an 82-degree temperature limit and did not exclude existing homes.

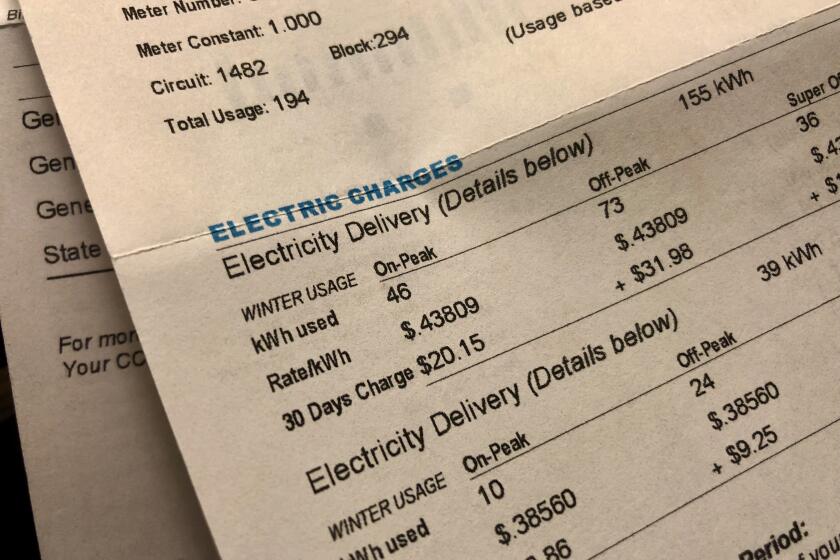

Electric bills are rising. Here are ways to reduce the burden without slowing the shift to home and vehicle electrification to meet our climate goals.

Is this really the best California officials can do?

Including existing rental units in statewide temperature limits is essential. California only builds roughly 100,000 new homes each year, and most are already likely to include air conditioning anyway. Leaving out existing homes may please landlords, who have opposed requirements to install cooling equipment because of the costs. But it would defeat the purpose of the standard, which is to save lives and protect the most vulnerable communities, whose less-shaded neighborhoods and older, less-insulated housing magnify their risks from extreme heat.

Instead of setting a temperature limit, the department makes other suggestions for existing units, such as policies to ensure renters at high risk for heat-related illness have the right to add cooling equipment and can afford to operate it. The document also encourages the installation of window coverings, shade trees, insulation, solar-reflective roofs and “broader adoption of fans,” which it highlights as a cheaper and more energy-efficient alternative to air conditioning because it costs about $400 to install a ceiling fan compared to $550 for a window A/C unit.

As California lawmakers negotiate a multibillion-dollar school bond, they should include plenty of money to green up asphalt-dominated schoolyards.

Housing, environmental, and climate justice advocates have pushed the housing department not to limit its recommendations to building standards for new construction. The fact that landlords may incur hundreds or even thousands of dollars in costs to retrofit their units is no reason to shy away from meaningful standards to protect people who are in unsafe conditions in their own homes. Instead, the state should offer solutions, like financial assistance to help property owners manage the expense of installing air conditioners for their tenants.

Extreme heat is the deadliest climate hazard and killed an estimated 3,900 Californians between 2010 and 2019, a Times analysis found. State health officials counted 395 deaths during one 10-day heat wave alone in 2022. And scientists project that if the rate of global warming continues, by mid-century 11,300 Californians could die from heat-related causes each year.

Statewide standards are needed because extreme heat is increasingly putting Californians in harm’s way, and not just in inland areas. People in California’s historically mild coastal regions are especially susceptible during heat waves, because they are not accustomed to such high temperatures and less likely to have air conditioning in their homes, and would be among the areas with the most to gain from cooling requirements.

Kyle Krause, deputy director of Codes and Standards for Housing and Community Development, said that the indoor cooling recommendations are not final and may still be changed before they are submitted to the Legislature. Good. They ought to be revised to make it clear to lawmakers and regulators that it’s time for California’s health and safety protections to change with the climate. No one should be exposed to life-threatening heat inside their home, no matter their ZIP code or type of housing.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.