Column: Never forget: Nicole Brown Simpson’s murder redefined our understanding of domestic violence

Weeks before she was slashed to death outside her Brentwood condo in 1994, O.J. Simpson’s ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, had predicted her own death.

“She knew exactly what was going to happen to her,” Nicole’s friend Kris Jenner told “Dateline NBC” in a 20th anniversary special episode about the murders of Nicole and Ronald L. Goldman, a waiter at a nearby restaurant who had gone to her condo to return a pair of glasses her mother had left on their table that evening. Nicole, said Jenner, had confided her fear: “Things are really bad between O.J. and I, and he’s going to kill me, and he’s going to get away with it.”

She was, devastatingly, correct.

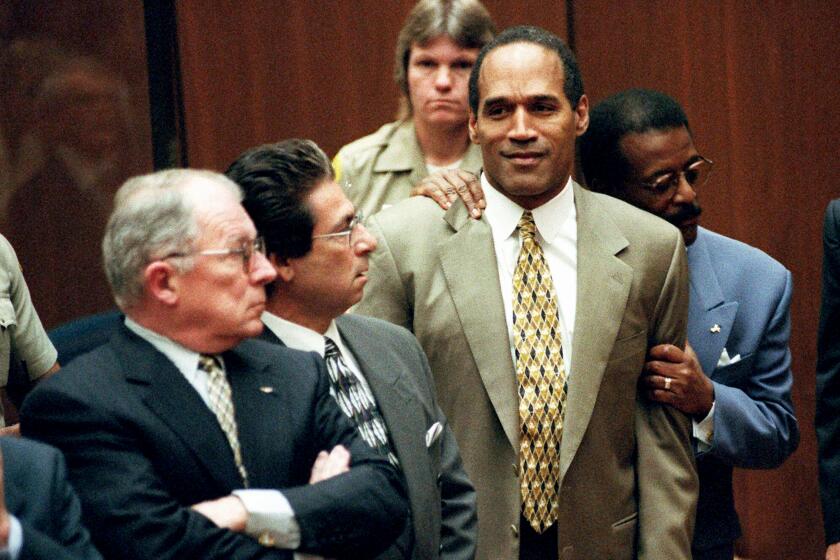

Although Simpson would later be found liable for the deaths of his ex-wife and her friend in civil court, a criminal court jury declared in 1995 that he was not guilty of the double murder. That verdict was a lot of things — nauseating proof of how celebrity worship warps justice, a primer on police malfeasance and egregious prosecution errors and, most especially, a racial Rorschach test.

It was also a travesty.

When news broke Wednesday that O.J. Simpson had died of prostate cancer at age 76, I felt an overwhelming sense of sadness — not for him but for Nicole Brown Simpson, Ronald L. Goldman, the lives they might have led and, of course, their families.

O.J. Simpson, whose rise and fall from American football hero to murder suspect to prison inmate fueled a public drama that obsessed the nation, has died.

Though so much has been said about how the Simpson case broke open racial fault lines in this country, we must never forget that Nicole Brown Simpson’s death helped change the way we think about domestic violence, and how we treat its victims and perpetrators.

After she died, we had to confront our misconceptions about domestic violence. Inside their mansion at 360 N. Rockingham Ave., Nicole was trapped in a classic cycle of violence, trying to please a man who was not just a philanderer and abuser but who was protected by the hero-worshiping officers of the Los Angeles Police Department.

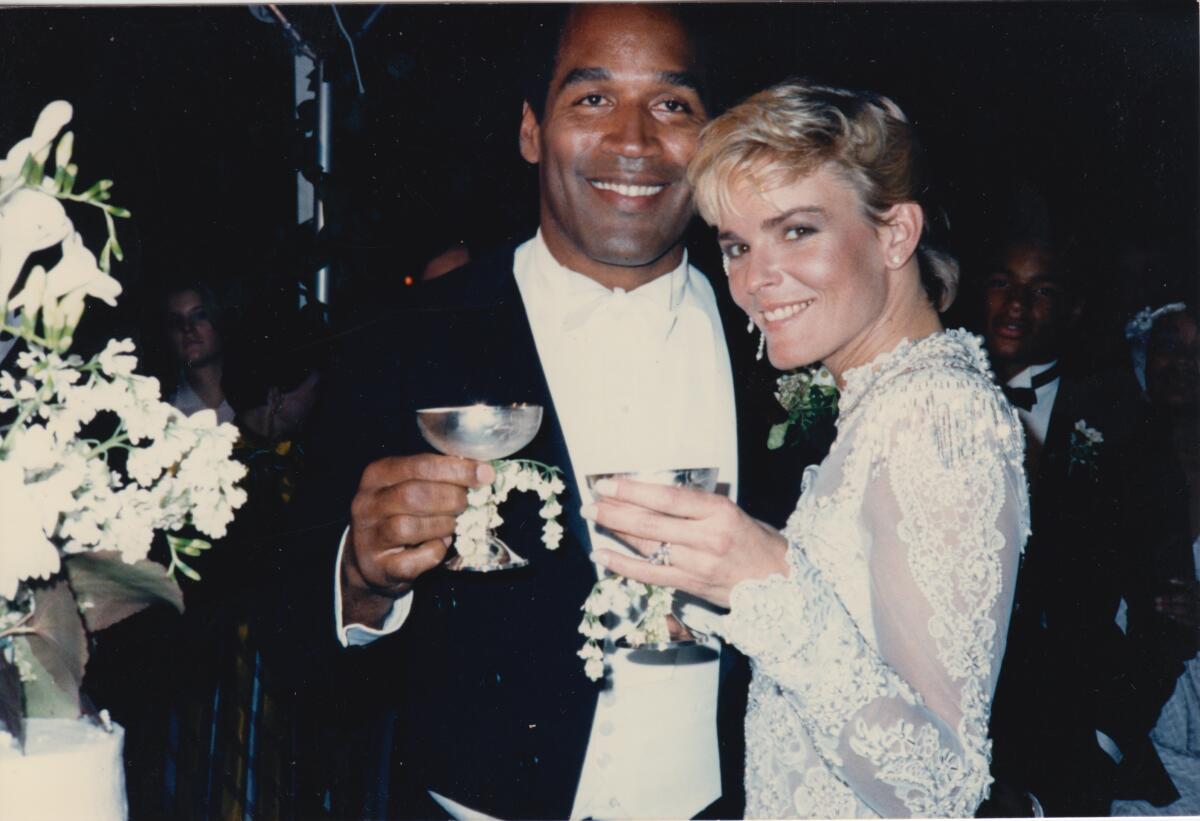

She had no reasonable expectation that she would be protected from the violence of her ex-husband, a football star and cultural hero who met her in 1977 when he was 30 and she was an 18-year-old waitress just out of high school. She had called the police eight times, to no avail.

Less than five months after the birth of their second child, in 1989, O.J. inflicted on Nicole what she described in a letter to him as “the mad New Year’s Eve beat up.”

When police arrived at their home, Nicole was shaking in her bra and sweatpants. The police report described her cut lip, swollen and blackened left eye and a hand print on her neck.

“He’s going to kill me,” she said over and over as she clutched one of the officers. “You never do anything about him! You talk to him, then you leave. I want him arrested. I want him out so I can get my kids.”

O.J. screamed at the cops, “The police have been out here eight times before and now you’re going to arrest me for this? This is a family matter!” He sped off in his blue Bentley, but was eventually charged with spousal abuse. Although the prosecutor recommended that he serve 30 days in jail, he was sentenced to 120 hours of community service and two years’ probation. He was ordered to donate a paltry $500 to a battered women’s shelter.

And rather than require him to participate in a yearlong group therapy program for batterers, which was standard, Simpson was allowed to have private sessions with a psychiatrist of his own choosing. The accommodation was requested by his attorneys to protect his privacy, and, of course, his reputation.

At the time, you may recall, the Hertz Corp. continued to air spots featuring Simpson running through airports. When the New York Times asked Hertz in 1994 whether it knew its celebrity spokesman had been convicted of beating his wife, the company did not respond.

In the beginning, she didn’t even recognize him, that’s how unworldly she was. “That’s O.J.

That would not be the case today.

“That was such a pivotal moment,” said Patti Giggans, executive director of the Los Angeles Commission on Assaults Against Women, which has since been renamed Peace Over Violence. “It was such a shock to the culture. There was so much denial and passivity around these issues. It launched awareness of domestic violence in a way that had not happened before.”

Her rape and battering hotline, said Giggans, “rang off the hook, mostly women.” Many of the questions were along the lines of, “This is what’s happening in my relationship; could what happened to Nicole happen to me?”

Giggans and her organization were besieged by reporters from around the world who were clueless about spousal battering. “One of my refrains,” she said, “was, ‘Not every relationship that has violence ends with someone being killed, but there is always that potential.’ People really started taking domestic violence more seriously.”

After the King beating and the 1992 riots, the LAPD forfeited the city’s trust. It isn’t surprising that jurors would have their doubts about the case the department built against O.J. Simpson.

And the system, which had failed Nicole so miserably, began to change.

“It was a sea change for a lot of things,” Giggans said. “There was more funding for shelters, advocacy and intervention. There were more opportunities for education. Government entities — whether law enforcement, district attorneys and the courts — have absolutely evolved in a positive way.”

To the end, Simpson was unrepentant, denying he had killed Nicole or Goldman. Like so many wife beaters, he saw himself as the victim.

“At times, I have felt like a battered husband or boyfriend, but I loved her,” wrote Simpson in a letter that was read to the media by his friend Robert Kardashian while Simpson was fleeing in the infamous white Ford Bronco. “If we had a problem, it’s because I loved her so much.”

No. No you didn’t.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.