O.J. Simpson, whose murder trial riveted and divided the world, dies at 76

O.J. Simpson, whose rise and fall from American football hero to murder defendant to prison inmate fueled a rancorous public drama that obsessed the nation and spawned debates over race, wealth, justice and retribution, has died of cancer, according to a family member’s statement on X.

It was not immediately clear where Simpson died, but his family said he was surrounded by his children and grandchildren when he died Wednesday. He was 76.

Simpson was once the country’s most admired athlete, a formidable running back who broke records with grace and determination. He became a crossover star, lending his handsome face and affable personality to the slapstick “Naked Gun” movies and classic television commercials for Hertz.

He served nine years of a 33-year sentence at Lovelock Correction Center, 90 miles northeast of Reno, after his 2008 conviction on armed robbery, kidnapping, conspiracy and other charges stemming from his attempt to recover valuable memorabilia he claimed had been stolen from him. His incarceration was widely viewed as long-overdue punishment for the 1994 slayings of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald L. Goldman.

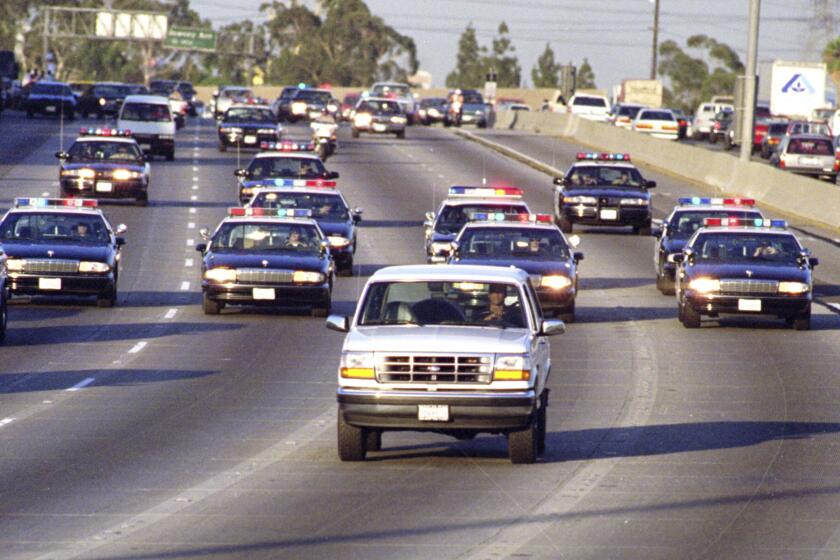

Friday is the 28th anniversary of the infamous slow-speed chase that fascinated California and the nation.

While much of the public presumed him to be guilty of the killings, the former USC Heisman Trophy winner was acquitted in 1995 in a spectacular trial that was rife with vexing questions, none more divisive than the one posed by Simpson’s defense team: whether a Black man in America — even one who had crossed racial barriers and attained significant wealth and status — could be tried without prejudice for the slaying of a white person. Polls showed deep fissures between Black people and white people on the question of his innocence. When a predominantly Black jury set him free, it drew those racial suspicions into even sharper relief.

“The only reason that we will care about O.J. Simpson 10 years after, 20 years after, is what it told us about race in this country,” said the New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin.

Simpson’s acquittal was only the first chapter in a long legal saga. In 1997, a predominantly white jury in Santa Monica found him liable for the deaths in a civil suit brought by the Brown and Goldman families. Ordered to pay the families $33.5 million in damages, Simpson gave up his Brentwood estate and moved to Florida, in large part to evade the civil judgment.

His desire to shield his assets set in motion the events that ultimately would bring him down: the robbery in a cheap Las Vegas hotel room in 2007. After a short trial that received minimal media coverage, the judge pronounced him guilty, 13 years to the day after the so-called Trial of the Century had set him free.

Orenthal James Simpson was born July 9, 1947, in a housing project in the depressed Potrero Hill section of San Francisco. He was the second of four children of Jimmie, a bank custodian, and Eunice, a night orderly at San Francisco General Hospital. He saw little of his father after his parents separated when he was 5. Simpson said in a 1977 Parents magazine interview that he resented his father’s absence, “especially when I became a teenager and was trying to find out who I was.”

He had rickets as a child and was left with spindly, bowed legs that attracted taunts from neighborhood kids. His mother fashioned a set of homemade leg braces that helped him improve enough to play football at Galileo High School. But his other extracurricular activity was stealing hubcaps and pies with a gang called the Persian Warriors. “I was always the leader — the baddest cat there,” he recalled.

He shaped up enough to enter San Francisco City College, where he scored 54 touchdowns in one season. At USC, he led the nation in rushing, running for 3,423 yards in two seasons, and in 1968, his senior year, he captured the highest honor in college football, the Heisman Trophy. He’d been a runner-up the year before.

He was snapped up by the Buffalo Bills in the 1969 National Football League draft but became problematic immediately when he demanded the largest contract in professional sports in the U.S. — $650,000 paid over five years. Initially Simpson disappointed but ended up leading the team in rushing for nine straight years.

In 1973, he broke NFL records by becoming the first runner to surpass 2,000 yards in a single season with a then-record 2,003 yards and broke Jim Brown’s single-season rushing record, once thought unobtainable. He was NFL Player of the Year in 1972, 1973 and 1975 but reached the playoffs only once and never got to the Super Bowl.

His style was idiosyncratic, known for twisting, fleet-footed runs that stymied the opposition. “O.J. gets right on top of you, looks you in the eye and then — pfft — he’s gone,” former Pittsburgh Steelers defensive lineman Joe Greene told Newsweek in 1975.

He went by O.J., but he was also known as “The Juice.”

In addition to his athletic gifts, he had what Newsweek’s Pete Axthelm called “an expanding, well-rounded personality” that was attractive to Hollywood moguls and Madison Avenue advertisers.

By the mid-1970s, the charismatic sports icon was acting in movies such as “The Towering Inferno” and “The Cassandra Crossing” and hurtling through airports as the star of a Hertz car rental television campaign.

He retired from football in 1979 after an undistinguished season with the San Francisco 49ers, the same year his 12-year marriage to the former Marguerite L. Whitley ended in divorce.

His first marriage produced three children: Arnelle, Jason and Aaren. In August 1979, Aaren, then 23 months old, drowned in the family swimming pool. Simpson rarely discussed the accident in public.

By then, Simpson was already dating Nicole Brown, whom he had met in 1977 when she was a waitress at a Beverly Hills nightclub, the Daisy. A former homecoming princess at Dana Hills High School in Orange County, she was blond, beautiful and 12 years his junior.

She dropped out of Saddleback College in Mission Viejo to move in with the famous running back and, after living together for several years, they were married on Feb. 2, 1985. Their first child, Sydney, was born that October. A son, Justin, was born in 1988.

When Simpson was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985, he thanked Nicole, noting that she entered his life “at what is probably the most difficult time for an athlete, at the end of my career. She turned those years into some of the best years I have had in my life.”

He became a sports broadcaster for NBC and ABC, including a brief run as a replacement for broadcaster Howard Cosell on “Monday Night Football.”

His pursuits enabled him to provide Nicole with a glamorous life. In addition to the $5-million Brentwood estate, they had second homes in Laguna Beach and New York, his-and-hers Ferraris and frequent vacations to Vail, Aspen and Hawaii.

But theirs was a volatile relationship. They fought and made up with regularity.

On New Year’s Day in 1989, however, an anonymous 911 call summoned police to the Simpsons’ home. When police arrived at 3:30 a.m., Nicole rushed out from the bushes where she had been hiding. Her lip was split, her eye was black and a handprint was visible on her neck. “He’s going to kill me, he’s going to kill me,” she cried, according to the police report. The famous former athlete emerged from the house, yelling, “I got two women, and I don’t want that woman in my bed anymore.”

Simpson pleaded no contest to domestic violence and was ordered to pay a $700 fine, obtain psychiatric counseling and perform 120 hours of community service. He also was placed on two years’ probation. The couple issued a statement, calling the altercation “an isolated and unfortunate incident.”

In 1992, the couple divorced. Simpson kept the Brentwood house while Nicole and the children moved into a townhouse a few miles away. He started to date model Paula Barbieri, but friends said he remained obsessed with his former wife.

On a 911 tape from Oct. 25, 1993 — widely aired after she and Goldman were killed — Nicole is heard pleading with the operator for help. She said Simpson had broken down her door and was “going nuts.”

There were several unsuccessful attempts at reconciliation. In late May, Nicole told her family that she was done with Simpson.

On June 12, 1994, Simpson attended a school dance recital for his daughter, Sydney. According to witnesses, he sat alone and glared at his ex-wife during the performance. When she left for a post-recital dinner party with her children, Simpson was not invited.

This much is certain about what happened over the next hours: After dining at a neighborhood restaurant, Mezzaluna, Nicole took the kids to get Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. Back home, her mother called around 9:40 p.m. to ask Nicole to retrieve a pair of eyeglasses she had left at the restaurant. Nicole reached her friend, Goldman, who was a waiter there. He said he would drop the glasses off after he left work around 10 p.m.

A little more than an hour later, a blood-streaked Akita dog would lead a good Samaritan to a grisly discovery: two bodies covered in blood outside Nicole’s Bundy Drive condo. When police arrived, they found Nicole, 35, with a deep, wide gash across her throat. Goldman, 25, had stab wounds to his throat, lungs and abdomen.

The children were asleep upstairs.

When the police tried to notify Simpson, they learned he had left on an 11:45 p.m. flight to Chicago for a meeting with Hertz executives. By the next day, his Rockingham Road estate had become a crime scene.

Police had discovered blood stains on the driveway and a bloody glove in the yard that appeared to match one recovered on Bundy Drive. They found traces of blood on a white Ford Bronco parked haphazardly at the curb. The estate’s famous resident quickly became the focus of the investigation.

The enduring image from the days immediately after the slayings would be the Bronco cruising down eerily empty freeways, trailed by a fleet of police cars. For seven hours on Friday, June 17, the celebrated former athlete eluded authorities who had planned to arrest him that morning. Behind the wheel of the Bronco was Simpson’s boyhood friend and former NFL colleague Al “A.C.” Cowlings. In the back, reportedly holding a gun to his own head, was Simpson.

Tipped by news reports, crowds gathered along the Bronco’s route as it sliced through Orange and Los Angeles counties. Some bystanders cheered, “Go, O.J., go!” as the Bronco passed, as if they were witnessing one of his legendary runs on the football field. Others held up signs: “We Love the Juice,” “Save the Juice.”

An estimated 95 million people — bigger by several million than the number who tuned into the Super Bowl that year — watched the slow-speed pursuit on television. Later, some commentators would trace the roots of reality TV to the surreal, 60-mile car chase that transfixed the nation and ended without violence in Simpson’s driveway, where he finally surrendered.

“Don’t feel sorry for me,” Simpson said in a suicide note his friend and attorney Robert Kardashian read at a news conference earlier in the day. The note ended with a plea: “Please think of the real O.J., and not this lost person.”

Laurie Levenson, a Loyola Law School professor who became a fixture as an analyst for CBS during the trial, said the chase and the case became a cultural touchstone.

“He really does define the combination of modern pop culture with the modern justice system,” Levinson said. “He was the origin of reality TV. You followed the Bronco. You followed the trial. You followed everything after. It’s like the Bronco chase continues.”

The trial opened on Jan. 24, 1995, in the downtown Los Angeles courtroom of Judge Lance Ito, whose decision to allow the proceedings to be televised was later heavily criticized. Quickly dubbed the “trial of the century,” it offered a cast of slick lawyers — Johnnie L. Cochran Jr. and Robert Shapiro leading the defense and Marcia Clark and Christopher Darden for the prosecution — and intriguing supporting characters, from sympathetic sister Denise Brown to rumpled houseguest Kato Kaelin. Vanity Fair writer Dominick Dunne called the trial “a great trash novel come to life.”

With no murder weapon or eyewitnesses, the evidence was purely circumstantial. But Clark promised the jury that a trail of blood evidence would lead them directly from the gory crime scene to Simpson’s mansion. The prosecution presented DNA findings that the blood found next to the size-12 shoeprints leaving the scene belonged to Simpson (who wore size 12 shoes), that blood found on a sock in his bedroom belonged to Nicole and that blood detected in his Bronco belonged to Goldman.

As for motive, the prosecutors portrayed Simpson as a jealous man obsessed with his ex-wife and frustrated he could no longer control her through expensive gifts, threats and beatings. He killed Goldman, Darden said, “because he got in the way.”

The defense demolished the DNA evidence, arguing that police conspired to fabricate and contaminate evidence. It turned a key exhibit — the bloody glove — into a symbol of official malfeasance. Not only did Simpson’s lawyers allege that the glove found in their client’s yard that matched one found at the crime scene had been planted by a racist cop — Det. Mark Fuhrman, whose derogatory references to African Americans and boasts about manufacturing evidence were exposed in court — but the gloves didn’t even fit when Darden asked Simpson to try them on.

“They’re too small,” Simpson said, struggling to pull on the gloves. Those were the only words he uttered to the jury during the 10-month trial.

The dramatic demonstration gave Cochran the line that cemented his closing argument: “If it doesn’t fit,” he intoned, “you must acquit.”

And less than a week later, the jury acquitted the celebrity defendant, after deliberating only three hours.

But Simpson was never truly free again.

The civil trial took place in 1996 and deepened the portrait of Simpson as an abuser. More liberal rules allowing hearsay evidence allowed lawyers for the Brown and Goldman families to use excerpts from Nicole’s diaries. The journal entries detailed incidents when Simpson terrorized her with a gun, shouted profanities at her, tried to coerce her into aborting their unborn son and threatened to turn her in to the Internal Revenue Service.

This time, Simpson testified.

He denied ever hitting or beating Nicole. Instead, he offered a picture of himself as a concerned husband who nursed her through pneumonia after their divorce and worried about her even after he became involved with someone else.

But his testimony failed to convince the mostly white jury. After deliberating for three days, they returned a unanimous verdict against him. Finding him liable for the deaths of Nicole and her friend was the closest the legal system could get to calling him a murderer.

Simpson was forced to sell his Brentwood home of 20 years at auction several months later; it was razed in 1998. Two years later, he moved to Florida, where the laws made it easier for him to shield his remaining assets. He lived off his $19,000-a-month NFL pension and investments.

In 2006, he wrote “If I Did It,” a bizarre “fictional memoir” about how he might have committed the murders. His potential to profit from the book stirred such outrage that the original publisher, Judith Regan, was fired and thousands of copies were destroyed.

In an effort to collect on the civil verdict, Goldman’s father, Fred, gained the rights to the book and had it published in 2007. The book, which became a bestseller, featured Simpson’s original manuscript but with an introduction by the Goldmans, who viewed the story as Simpson’s confession. Taking the book away from Simpson was a coup for the Goldmans, whose lawyers constantly dogged him to turn over valuables.

Fred Goldman later speculated that losing the book pushed Simpson over the edge.

On Sept. 13, 2007, he assembled a rogue’s gallery of ex-cons to confront memorabilia dealers Bruce Fromong and Alfred Beardsley, whom an intermediary had lured to a room at the Palace Station Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas. Told to expect a “mystery buyer,” they were stunned when Simpson burst into the room with his ragtag band of cohorts, two of whom brandished guns as Simpson demanded the return of a number of items he said belonged to him. He left with a bag full of mementos, including an All-American team football and three game balls inscribed with the dates he used them to break records.

Simpson was arrested three days later on charges including armed robbery and kidnapping.

At his trial, there were empty seats in the courtroom.

At his sentencing, Simpson was contrite.

“In no way did I mean to hurt anybody, to steal anything from anybody. I just wanted my personal things,” he told the judge after hearing his sentence. Then, with wrists shackled to a chain around his waist, he was taken to his cell.

For the record:

2:39 p.m. April 11, 2024An earlier version of this obituary used the wrong name when describing Simpson leaving Lovelock Correctional Center. The error has been corrected.

Long before the city woke up on a fall morning in 2017, Simpson walked out of Lovelock Correctional Center a free man for the first time in nine years. He didn’t go far, moving into a 5,000-square-foot home in Las Vegas with a Bentley in the driveway.

The media had been told he’d be released the following day, so he had the desert morning to himself as he was driven away. It was a final trick play for a man who’d spent a lifetime running away from trouble.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.