Commentary: From the Brentwood townhouse to the downtown courthouse, the O.J. Simpson saga was part of my life

Two murders in Brentwood? That was unusual, I thought, as word filtered through the newsroom on a Monday afternoon in June 1994 that two people were found dead in the upscale neighborhood — and one of them was Nicole Brown Simpson, the former wife of O.J. Simpson. The other victim was her friend Ron Goldman.

With O.J. Simpson’s death from cancer Wednesday, memories of the saga that consumed the city, my newspaper and — because I lived in Brentwood — my neighborhood came flooding back.

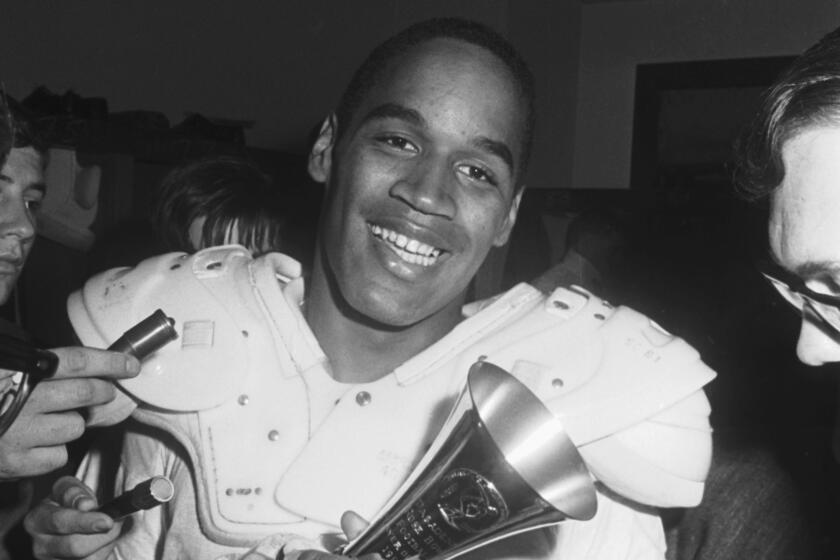

O.J. Simpson, whose rise and fall from American football hero to murder suspect to prison inmate fueled a public drama that obsessed the nation, has died.

In the newsroom, four days after the bodies were found, reporters and editors clustered around a TV to watch then-Los Angeles Police Cmdr. David J. Gascon announce that there was a warrant for Simpson’s arrest, but he was nowhere to be found. “The Los Angeles Police Department right now is actively searching for Mr. Simpson,” he said. The newsroom erupted into one big cry of “WHOOAAA…!” drowning out what Gascon said after that. It was probably the most dramatic moment I ever witnessed in the newsroom.

My day was a blur from there. As part of the team of L.A. Times reporters covering the story, I went to the news conference where Robert Kardashian — Simpson’s friend and lawyer, whose children would grow up to be ridiculously famous — read the letter Simpson left behind before he set out on his infamous odyssey in a white Ford Bronco. It read like a suicide note and was signed “Peace and Love, O.J.” with a little smiley face in the O.

In a lot ways, many of us remain locked in our bubbles, not entirely understanding the thought processes of people of other races and ethnicities.

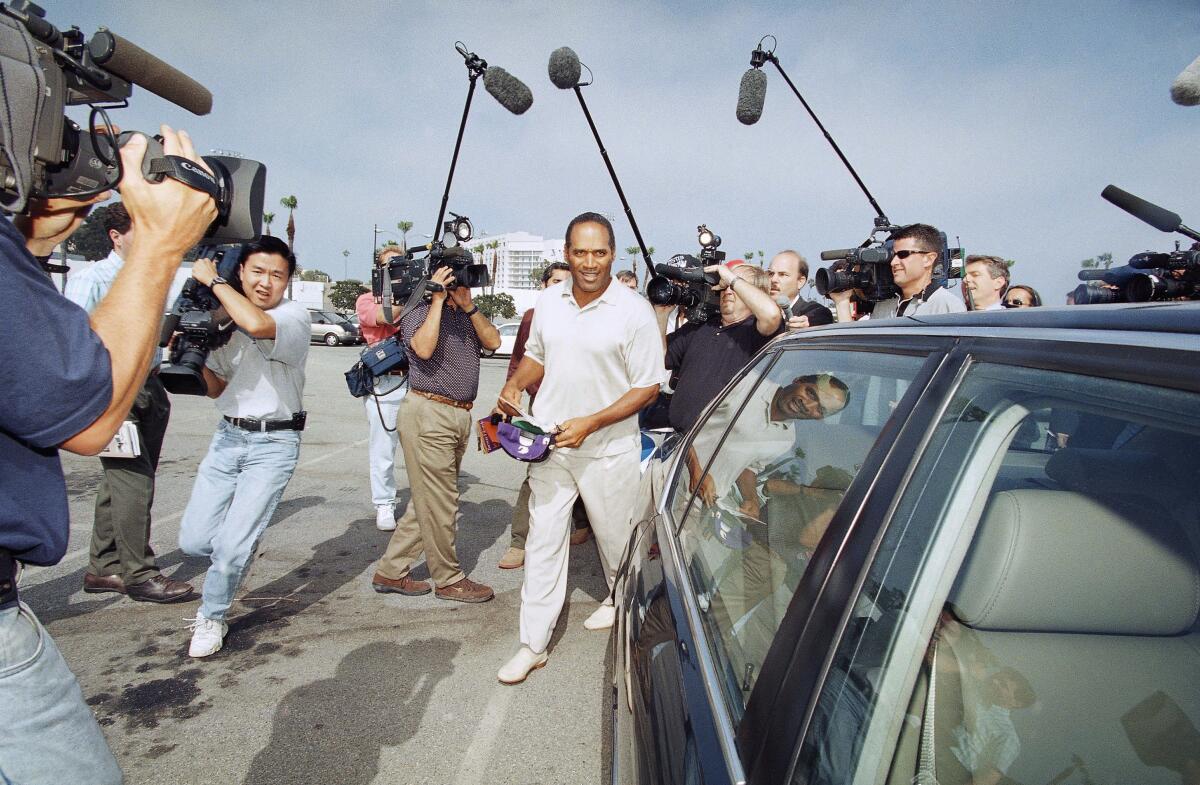

I chronicled the overnight transformation of Brentwood into a destination for throngs of gawkers. They packed Mezzaluna, the restaurant where Nicole Simpson ate her last meal and Goldman worked as a waiter. They traipsed by her townhouse on Bundy Drive as if in an audience-participation murder mystery. Neighbors were appalled.

So many people drove by Simpson’s mansion on North Rockingham Avenue that the city temporarily closed it to nonlocal car traffic at the entrance to the street from Sunset Boulevard. I remember walking the street and some angry teenage boys lounging outside a big house screamed at me to leave the neighborhood. I was so offended. I was working while these rich slackers were amusing themselves by trying to kick people off a public street.

Everything about this tragedy became a story and we documented it all. I covered Nicole Simpson’s funeral, where her female friends showed up in fashionable close-fitting black dresses and suits that looked like cocktail party attire. (California’s current Republican candidate for Senate, Steve Garvey, was there.) In 1995, I toured Nicole Simpson’s townhouse with a real estate agent and wrote about how there was little interest in this beautiful but notorious home.

USC, the Buffalo Bills and NFL were silent following O.J. Simpson’s death Thursday, a clear indication of how far the superstar fell from grace.

Goldman had lived in an apartment a block away from me. Good friends of his lived even closer — and I walked there to interview them for a profile I co-wrote. O.J.’s murder trial in 1995 may have been the centerpiece of our daily coverage, but there was much more to write about. There were the people who showed up to get into the courtroom, the souvenir vendors outside and the shoeshine worker at the courthouse.

I spent time with Arnelle Simpson, O.J.’s daughter from a previous marriage, for a profile. She was a 26-year-old Howard University graduate, thoughtful and candid, never doubting of her father. She talked most nights on the phone to him in jail and cut back on her work as a wardrobe stylist to go to court to support him.

Even with the verdict in the Rodney King beating trial and 1992 riots still a fresh and painful memory, this story to me involved so much more than race. O.J. may have been a Black man sitting in jail, accused of murdering his beautiful blond ex-wife, but he was also incredibly famous, a football hero and movie actor who charmed people and moved easily in one of the whitest neighborhoods in the city. Years later when I was doing research to write Johnnie Cochran’s obituary, I was struck by how the skillful lawyer had shown that there were demonstrably racist police officers involved in handling key evidence. I talked about that with a former colleague who had covered the trial and he said, “Well, the cops could be racist, and O.J. could be guilty too.”

After the King beating and the 1992 riots, the LAPD forfeited the city’s trust. It isn’t surprising that jurors would have their doubts about the case the department built against O.J. Simpson.

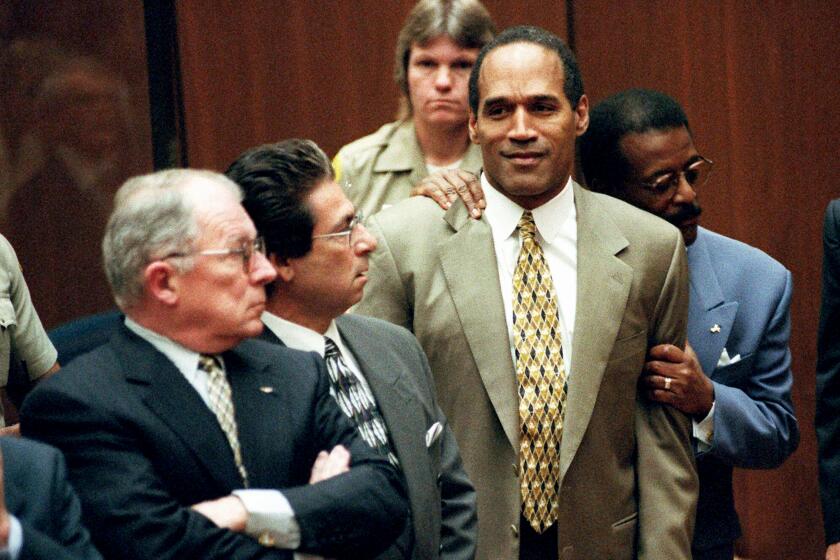

The morning the verdict was read, I was standing in the long hallway outside the courtroom, jammed with reporters and other observers. As we waited, the suspense engulfed us all. On a bench against a wall, I saw Jason Simpson, O.J.’s 25-year old son, quietly weeping. Nerves, I thought. We listened on handheld radios for the verdict to be announced. (Rare was the person with a cellphone back then.) Someone down the hall heard first and shrieked out the jury’s decision. Soon the doors opened, and now it was Kim Goldman, Ron’s sister, I watched sobbing as she walked out.

The Los Angeles Times put out an Extra edition that morning.

On Thursday when news of his death broke, a source texted me that he was talking to a 20-something colleague about O.J. and “She barely had any idea who he was. LOL.” Yeah, LOL indeed.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.