The photo that wrapped Marlon Brando’s homoerotic swagger in a tight leather jacket

Book Review

Marlon Brando: Hollywood Rebel

By Burt Kearns

Applause: 296 pages, $29.95

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

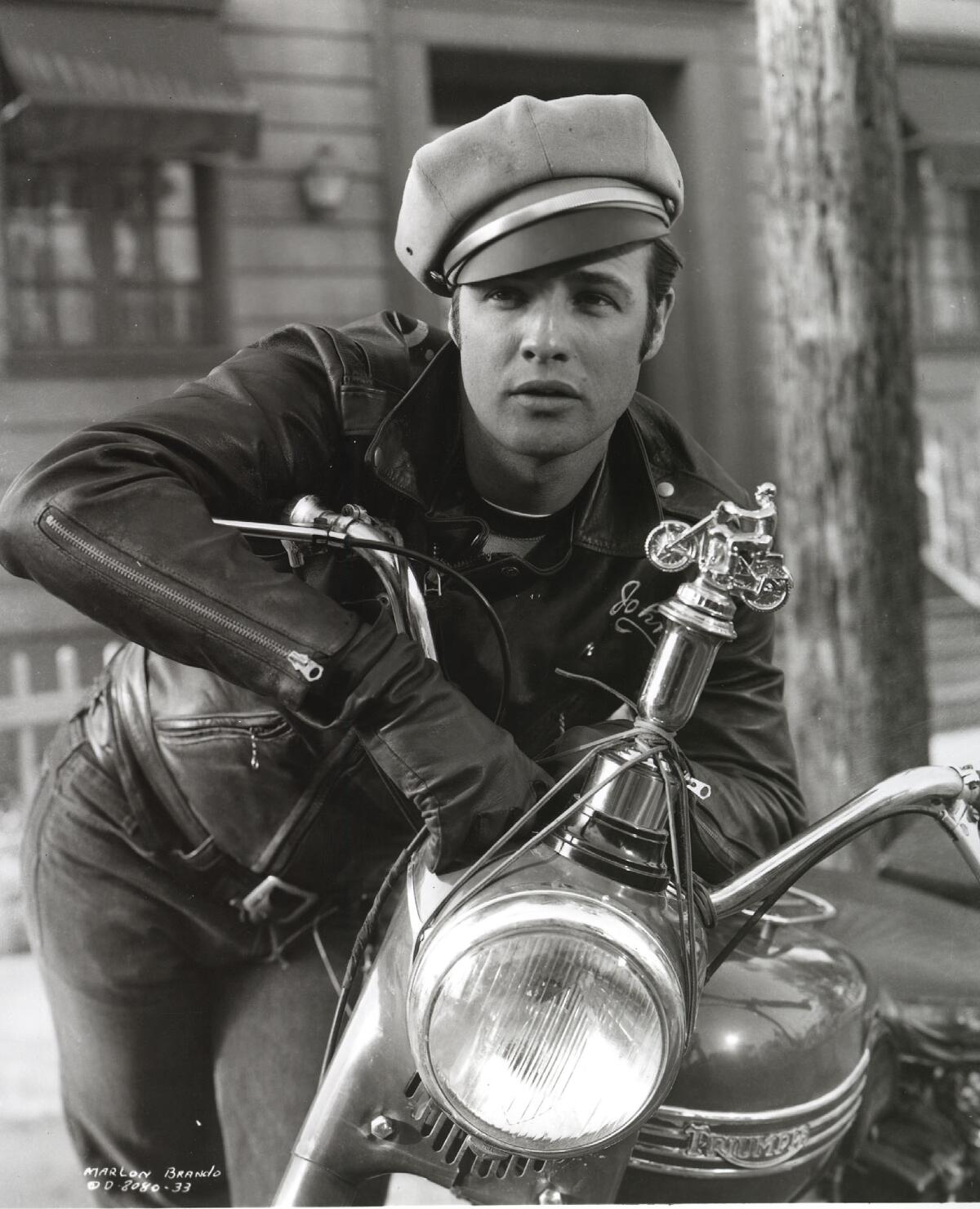

He leans over the handlebars of his motorcycle, zipped up in a black leather jacket, his biker cap tilted over his right eye. His lips slightly parted, his eyes inquisitive, he instantly embodies contradictions: tough and vulnerable, fearless and scared, masculine and feminine.

This image of Marlon Brando from the 1953 film “The Wild One,” absorbed by the likes of Elvis Presley, James Dean and John Lennon, immortalized in the pop art of Andy Warhol, has had an almost subliminal impact on the American psyche.

“The Wild One” is nowhere close to Brando’s best movie or best performance. But this singular image, culled from an 89-minute film, somehow plumbs the depths of our thoughts and feelings on masculinity and rebellion.

Biographer Brad Gooch’s “Radiant” reveals how much life and creativity artist Keith Haring packed into 31 years before he died of AIDS.

Burt Kearns’ new book, “Marlon Brando: Hollywood Rebel,” is not, the author takes pains to explain, a Brando biography. There have been many of those, including the actor’s own “Brando: Songs My Mother Taught Me” (written with Robert Lindsey).

“Hollywood Rebel” is, as the author writes, “a study of how one man’s artistic and personal decisions affected not only those around him, but all of Western society and popular culture.” But at its most incisive the book is a biography of this specific image from Brando’s late 20s, the biker portrait seen ’round the world, recognizable and indelible even to those who have never seen the movie from which it was extracted.

“The Wild One” was based on the Frank Rooney short story “Cyclists’ Raid,” which in turn was based on the 1947 invasion of the Central California town of Hollister (near Monterey) by thousands of rowdy bikers over a turbulent Fourth of July weekend. As Kearns writes, post-World War II motorcycle “gangs” were generally populated by veterans set adrift in a new world after their service ended. “Cyclists’ Raid” caught the attention of producer Stanley Kramer, who specialized in progressive “social problem” movies, including one he had just made with Brando, “The Men,” in which the rising star played a paralyzed vet.

When Brando signed on to star in “The Wild One” he was hot off the success of the film adaptation of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” which had made him a young Broadway legend when it premiered there in 1947. In “Streetcar” Brando played Stanley Kowalski as a virtual fire hose of sexuality, a brute in a tight white T-shirt (and, though the film conveys the point with Production Code-mandated subtlety, a rapist). This was a new kind of screen carnality, raw and visceral, and Brando, a mumbling powerhouse, was a new kind of star.

James Kaplan’s triple biography weaves together ‘3 Shades of Blue’ in the backstories of Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Bill Evans at the height of jazz’s cultural sway.

But “The Wild One” was newer still. As Kearns observes, the movie’s homoerotic subtext quickly becomes homoerotic text. Brando’s Johnny Strabler, pouty with a slight Southern lilt, engages in a frenemy relationship with a rival biker, Chino (played by Lee Marvin), who behaves more like a jilted lover than a fellow road dog (“I love ya, Johnny!” he repeats over and over; during a fistfight Johnny knocks Chino through a store window, where he lands smack in between bride and groom mannequins).

Johnny seems utterly baffled by, if not terrified of, the opposite sex, represented by a townie (Mary Murphy) looking to spice up her small-town existence and a biker moll (Yvonne Doughty) with fond memories of a one-night stand.

Then there’s that tight leather, which would make Brando-as-Johnny a sort of butch fetish object for gay fans, artists and filmmakers, including Warhol, who used the famous image in multiple works; and Kenneth Anger, whose 1963 avant-garde short film “Scorpio Rising” features clips of Johnny cruising on his bike.

That Brando himself freely discussed his sexual adventures with both men and women made the homoerotic symbolism of “The Wild One” both easier and more resonant.

Lest you think the film influenced only gay subculture, Kearns also details its impact on rock ’n’ roll, particularly on a shy megastar from Memphis, who openly proclaimed his Brando worship, and a group of lads from Liverpool.

In one scene, Chino is lamenting to Johnny that “the Beetles” miss him, apparently alluding to the gang’s groupies. And yes, this was seven years before a certain band began to call itself the Beatles. John Lennon was on record as a huge Brando and “Wild One” fan. Kearns builds a compelling case for this origin story of the band’s name as he goes down one of the book’s many rabbit holes, some more rewarding than others.

The big picture is much clearer. Brando, and especially this Brando, has had an outsize influence on American culture and our conception of how a rebel behaves. “What are you rebelling against?” Johnny is asked as his gang makes itself at home in small-town California. His famous response: “Whaddya got?” Brando-as-Johnny grew into an all-purpose symbol of revolt, against norms in society, sexuality, fashion, music … and whaddya got. (Two years later came “Rebel Without a Cause” and another timeless jacket, this one a red nylon windbreaker.)

“Hollywood Rebel” occasionally wears out its welcome. Kearns has a habit of extensively, excessively quoting the same handful of expert sources. He sometimes overstates his arguments, as when he calls the Hollister biker invasion “one of the most influential public disturbances since the Boston Massacre” (one could imagine many rivals for that list, from the Civil War draft riots, to Vietnam protests, to Watts, to Ferguson, to the Jan. 6 insurrection). The author also seems a little too proud of his prolific double-entendre usage, even for a book that is largely about sexual magnetism.

On balance, however, “Hollywood Rebel” is a worthy addition to the Brando bookshelf, largely because the author picks an idea and never loses sight of it, even as he fans across multiple disciplines to explore the idea. This is a book about how one facet of one man captured in one image from one film can send ripples through the world.

Chris Vognar is a freelance culture writer.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.