Book Review

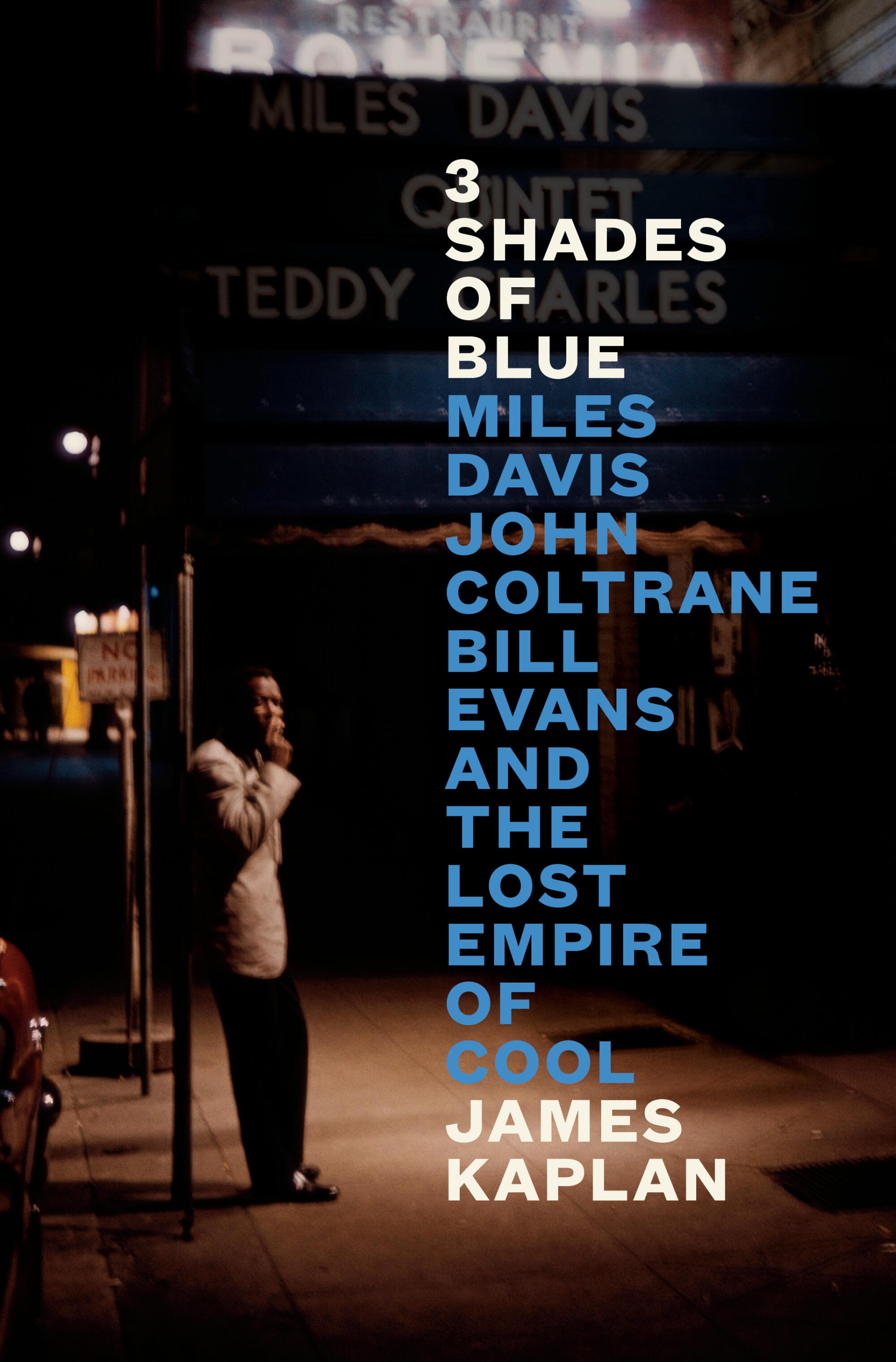

3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Bill Evans and the Lost Empire of Cool

By James Kaplan

Penguin: 484 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

You know exactly where “3 Shades of Blue” is heading from the first page, even from the front cover. You foresee the point at which its three shades will blend and blur and, for an incandescent moment, become one. But the anticipation and excitement still never abate.

Frank Sinatra biographer James Kaplan has set his sights on three jazz giants — Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Bill Evans — as their lives and their art lead up to the recording of “Kind of Blue,” Davis’ landmark 1959 album that featured Coltrane on tenor saxophone and Evans on piano. The album marked a commercial and creative peak in jazz, the summit of what Kaplan, in the book’s subtitle, calls “The Lost Empire of Cool.”

Along the way we meet a supporting roster comprising some of 20th century music’s greatest minds and talents.

There’s Charlie Parker, the sax virtuoso who, along with trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, all but created bebop, and who left many followers scrambling to emulate his every move — including, tragically, his insatiable heroin addiction.

There’s Thelonious Monk, the bearlike composer and pianist who thought in rhythms that others couldn’t fathom.

There’s Ornette Coleman, the Texas-born saxophonist whose experiments went further out than even Coltrane (for a time, anyway) and left many listeners and peers baffled and even angry.

In a sense “3 Shades” is an ode to a time when people cared enough to get angry about jazz. As Kaplan writes: “Jazz today, when it isn’t utterly ignored, is widely disliked for different reasons: because it is old, or anodyne, or hard to understand. Jazz is passé. Jazz is niche. Jazz is the smooth soundtrack to polite brunches in restaurants with potted ferns and bananas Foster and clever young servers.”

’Twas not always the case. Kaplan’s book is a bracing reminder of when jazz represented a widely relevant culture, when New York’s 52nd Street teemed with crowded new venues and new sounds, when the faces of Davis and Monk appeared on mass-circulation magazines (remember those?) and Columbia Records could market Miles as not just a jazz artist but as an artist, period, who appealed to anyone seeking great, adventurous music.

Miles, still one of those artists who deserves the first-name-only treatment, is at the center of it all, at once white-hot and impossibly cool, seemingly always a step ahead of everyone else.

Kaplan himself interviewed Miles for Vanity Fair back in 1989, an encounter that provides an entertaining opening to the book. But for this book the author leans heavily on the engaging if not always reliable 1989 autobiography “Miles” (written with Quincy Troupe), describing Miles as a painter, constantly seeking to add the right sound colors to the palette in his head.

Miles idolized Parker and Gillespie, sought them out in New York and joined the bop revolution, eventually growing disillusioned, like so many, with Parker’s addiction and the chronic unreliability it fostered. Kaplan has no qualms about showing how the great Parker could be a selfish jerk, generally using the words and recollections of the artist’s peers to do so.

Miles teamed up with composer-arranger Gil Evans (no relation to Bill) on the groundbreaking nonet sessions that became “The Birth of the Cool,” blazed a trail through hard bop with his first great ’50s quintet, pioneered modal jazz with “Kind of Blue,” started a completely new quintet in the ’60s and just kept innovating (and self-destructing) through fusion and beyond.

As Kaplan writes of the young Miles, “He was a prince and a genius; he knew it.” He also could be ruthless as he cycled through collaborators and styles.

The book interweaves the stories of Miles; the spiritually seeking, soft-spoken Coltrane; and Evans, the classically trained pianist who stood out for both his blinding talent and his glaring whiteness. Coltrane’s fellow Philadelphia sax man Benny Golson recalls his first impression of Evans: “He looked like a college student, majoring, perhaps, in archaeology or advanced botany.”

There’s also a fourth main character, a destroyer rather than a creator: heroin. All three men were addicted at one time or another, and they paid many prices. Their playing suffered, as did their health and livelihoods.

Parker’s shadow looms large here; he had a reputation for playing well high, so others assumed they could too. Miles and Coltrane kicked heroin pretty early on, though Miles kept compensating with cocaine and booze. Coltrane’s recovery led him to the spiritual heights of 1965’s “A Love Supreme” before he died of liver failure in 1967 at the age of 40.

Evans remained a user for much of his short life, dying in 1980 at the age of 51. Here Kaplan quotes jazz historian and critic Gene Lees: “Bill Evans committed the longest, slowest suicide in musical history.” Miles stuck around until 1991, when he died of pneumonia at age 65.

Kaplan knows some music theory, enough to conjure the ideas behind specific styles and sounds without getting inaccessible. But mostly, he’s a master biographer, a dogged researcher and shaper of narrative, and this is his most ambitious book to date. His two-volume Sinatra biography is certainly longer, but here he shows his instinct for juggling and connecting multiple stories and characters without taking his eye off the big picture of how jazz interacted with art and culture in the second half of the 20th century.

There have been some fine jazz books in recent years, including Robin D.G. Kelley’s Monk biography “Thelonious Monk”; Aidan Levy’s Sonny Rollins biography “Saxophone Colossus”; and Judith Tick’s “Becoming Ella Fitzgerald.” “3 Shades of Blue” is playing with higher stakes.

It’s a compulsively readable work of fine synthesis and perspective that draws on others’ previous work and the author’s own interviews (particularly generous were Miles’ trumpet protégé Wallace Roney, who died of complications from COVID-19 in 2020; and Rollins, who continues to defy actuarial jazz odds at age 93).

There’s so much going on in the story of jazz that the “Kind of Blue” moment feels a little anticlimactic, another high point in a story full of peaks and valleys. A handful of musicians — including Davis, Coltrane and Evans — entered a studio, jammed on some modal ideas sketched out by Miles and came up with musical ambrosia. Then they went their separate ways, never again to play as a group. What they left behind is the stuff of legend — and now, a superb book.

Chris Vognar is a freelance culture writer.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.