Column: Censorship rears its ugly head at Santa Monica College, over a play about slavery

Happy Banned Theater Week!

How (sadly) appropriate that this annual celebration of taboo plays has been taking place (it ends today) in the wake of Santa Monica College‘s canceling of all performances of a new play that takes slavery and racial reconciliation as its topic.

“By the River Rivanna” was written by G. Bruce Smith, a former journalist with whom I competed as a cub reporter many years ago when we both covered Oxnard city government. Since then, I have had only casual contact with Smith, who served as SMC’s spokesman for many years.

Smith emailed me a copy of the two-act play, which I, of course, devoured, looking for instances of racial insensitivity or an unpalatable romanticization of slavery, as his critics have charged.

What I found was a provocative story about a successful, Ivy League-educated young Black man who has long repressed his family’s traumatic enslaved past and begins to have disturbing dreams about his Yoruba ancestors. He finds a journal, handed down in his family for generations, that was written by his enslaved great-great-great-great grandmother who lived on the fictional Hope Plantation in Virginia in the 1850s. She is unhappily married to a man who has a sexual and, yes, romantic relationship with the plantation owner, who is portrayed as deeply conflicted about slavery.

The play’s characters speak in a dialect that seems appropriate to their places in time and history. Over the course of many discussions as the play was cast and rehearsed, Smith deleted a single use of the N-word because it unsettled the white actor who would have had speak it. He also deleted the sounds of an offstage whipping. And two actors that he cast — a Black woman and a white man — dropped out because of the play’s content.

‘By the River Rivanna,’ depicting a gay romance between a slave owner and an enslaved person, has divided administrators, faculty and students at the community college.

The remaining student actors, Smith said, “put their heart and soul into it.”

Two weeks before the first of six performances was to take place on Oct. 20, there were rumblings of trouble. The play’s director, Perviz Sawoski, chair of the college’s theater arts department, was forwarded an email from a student who was offended that it was written by a white man and directed by a South Asian woman. “It’s not their story to tell,” the student wrote to a school administrator.

School officials were invited to rehearsals and met with the cast. My colleague Ashley Lee chronicled the complicated series of events leading up to the cancellation.

The bottom line: Instead of letting people see the play and decide for themselves what to think, SMC administrators pulled the plug. Sort of.

Book-banning typically pits small groups of prigs and right-wingers against the community, but communities are fighting back.

They orchestrated a vote of cast members, some of whom, Smith said, were deeply rattled by the threat of protests and a plan to have campus police present at the first performance. Smith said that the campus police chief told them if protesters breached backstage during a performance, they could grab fire extinguishers to defend themselves.

“A couple of them said they were really scared,” Smith told me. “I could tell by their faces they were more and more dejected.”

In a final vote, 12 students wanted to perform the play for invited guests only and eight voted against performing it at all.

“Students said, look, if eight people don’t want to continue, we can’t do that show,” said Smith. “In my opinion, that’s what the administration wanted: to turn around and say, ‘It wasn’t us. It was the students.’ ”

The student body president issued a statement that was quoted in the school paper, the Corsair, claiming the play “perpetuates problematic themes and discourse” by “centering of white perspectives and voices in telling a story about Black experiences.”

Giving residents censorship rights over librarians and the public crosses a clear line that should never be breached.

Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t. But how would she know if she’d never seen it?

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression has accused SMC of violating the 1st Amendment and Sawoski’s academic freedom. Administrators have declined to comment, citing the “threat of litigation.”

The censorship impulse on both extremes of the political spectrum is strangling discourse, critical thinking and, really, the human spirit. As a writer, I have to believe in my bones that anyone can write about anything.

“Porgy and Bess,” the great — and yes, controversial —1935 opera was written by three white men (the brothers Gershwin and DuBose Heyward) who insisted on an all-Black cast, a radical move at the time. The work was once described by James Baldwin as “a white man’s version of Negro life,” but wouldn’t you agree that the world is enriched by songs like “Summertime” or “I Loves You, Porgy”?

Mark Twain’s 1894 masterpiece, “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” is nothing if not a powerful indictment of the evils of slavery, despite its repeated use of the N-word. Told from a white point of view? Yes, but a brilliant and moving story nonetheless.

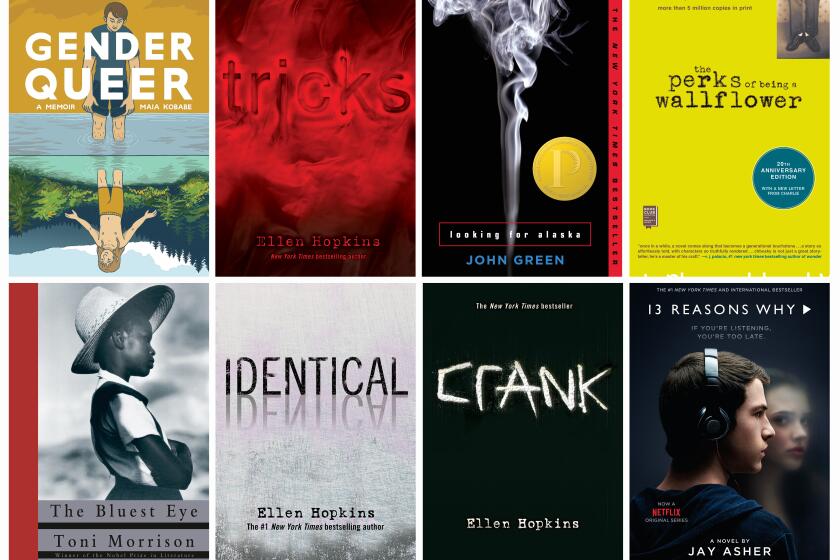

Books, literacy and freedom of expression are under assault as never before. A new report shows that book bans at U.S. schools increased 33% since just last year.

In 2021, the Columbia University linguist John McWhorter, who is often described as a Black liberal, wrote “Woke Racism: How a New Religion has Betrayed Black America,” about the excesses of what he describes as “Third Wave Antiracism,” embodied in the work of writers and thinkers such as Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo. McWhorter lists a bunch of contradictory new rules for white people that spring from their work.

One seems particularly apt in light of the fate of “The River Rivanna.”

On one hand, he writes, “you must strive eternally to understand the experiences of Black people.” On the other hand, “you can never understand what it is to be Black, and if you think you do, you’re a racist.”

Smith experienced this sort of dissonance from critics of his play: “On one hand, they said the play romanticizes slavery. On the other hand, they said the whipping, which we deleted the sound of, was triggering or traumatic. So which was it?”

In 2012, Smith wrote “Heart Mountain,” a play about a Japanese American family who were incarcerated in a camp after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was performed at SMC without incident and was selected for the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival’s regional competition.

“I think things have really changed on college campuses,” said Smith in perhaps the understatement of the year. “It’s been really eye-opening for me.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.