Column: Not satisfied with schools, book banners are now targeting adults’ right to read

It’s Banned Books Week, the American Library Assn.’s annual observance of attacks on freedom of speech and the freedom to read, and the news is not good.

Over the last year, according to Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, what has been most striking is the pivot of censorship advocates from books in school libraries to books in public libraries.

“Last year, about 16% of demands to remove books involved public libraries,” Caldwell-Stone says. “This year, to date, it’s 49%.”

We’re seeing groups go to school or library board meetings to demand the removal of multiple titles all at once — 25, 50, 100 titles or more, often based on lists they get from advocacy groups on social media.

— Deborah Caldwell-Stone, American Library Assn.

That’s a sea change, she told me, because “public libraries are the places that we’ve created for freewheeling inquiry, for the marketplace of ideas. Demands to remove books because they don’t comport with someone’s beliefs or their political or religious agenda are attacks on the very thought of a library as a place that protects 1st amendment rights to access a wide variety of views.”

These amount to demands that “the government tell us what to read, what to think, what to believe,” she says.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Other than that, not much has changed in the last year about demands for censorship of material accessible in public, except for two things.

First, there’s more of it: This year through Aug. 31, the ALA has tracked 695 attempts to remove or otherwise restrict access to library materials, aimed at 1,915 titles. That’s an increase of 20% in the number of titles challenged, making 2023 a high-water mark in a database that dates back 20 years.

The association says most of the challenges concerned books written by or about a person of color or a member of the LGBTQ+ community.

The second change is that a backlash has been gaining strength among parents and others who don’t want their kids or themselves deprived of access to books because fringe members of their communities want to impose their beliefs or political ideologies on everyone else.

It’s a “multi-pronged” fight, says Suzanne Nossel, chief executive of PEN America, the advocacy group for writers, readers and free expression generally, waged in court and state legislatures as well as before city, county, school and library boards.

“Overwhelmingly, Americans reject book bans,” Nossel says. “They know this is not the concept of free speech that we all are raised with and that we are proud of. When they point out that students have rights and that ‘parents’ rights’ are not just the rights of a single individual who may be objecting, but the rights of the overwhelming majority of parents who want their children to have the freedom to read, they can assert themselves and get these bans reversed.”

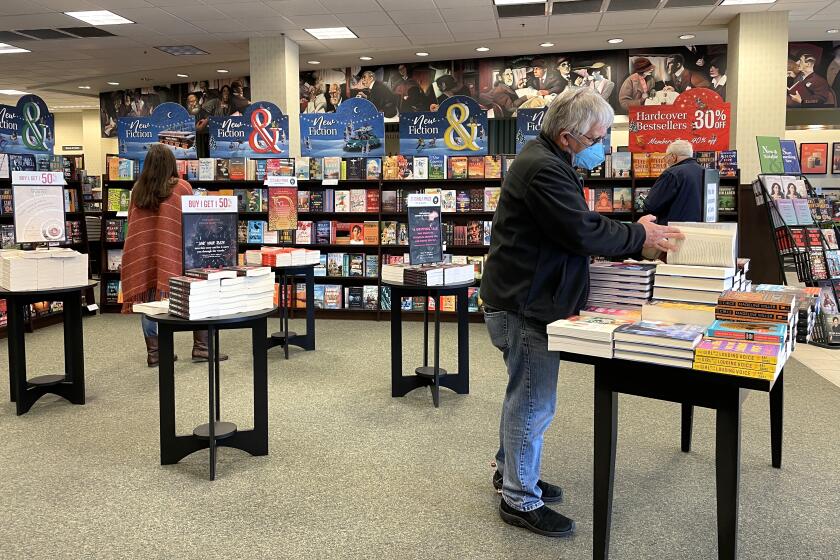

Barnes & Noble was on the verge of disappearing, like Border’s and Waldenbooks. Under new management it’s turning around, and that’s good news for readers.

California last month became the second state to ban book bans in public schools, when Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a measure imposing financial penalties on districts that ban textbooks portraying LGBTQ+ people and other marginalized groups.

The law was partially in response to a right wing-dominated school board in Temecula, which tried to reject curriculum materials that mentioned slain gay leader Harvey Milk. The law allows the state to override a board and provide the materials to students at the district’s expense.

The first-in-the-nation measure outlawing book bans was signed in June by Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker. That law strips public libraries of state funding if they restrict or ban materials for “partisan or doctrinal reasons.”

I should declare a personal perspective here. We read with our kids every night when they were growing up — Narnia, yes, but also “Huckleberry Finn,” unexpurgated, and never discouraged them from reading anything on their own. They grew into smart, knowledgeable, inquisitive adults.

When I was in school, we knew families that imposed stringent limitations on what their kids could read or watch, but we found them peculiar. None of them sought to impose their practices on anyone else, however — the defining characteristic of today’s book banners.

Things began to change in the 1970s. In that period, the school board in a district neighboring the one I grew up in, following along with a right-wing parents organization, ordered nine books removed from its secondary school libraries as “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Sem[i]tic, and just plain filthy.”

The board was slapped down by the Supreme Court in a landmark 1982 opinion finding that decisions to remove books once they had been acquired could not be “exercised in a narrowly partisan or political manner,” as was the case there. That was the last time the court ruled on a book ban, and it remains binding precedent.

Defenders of book-banning often conceal their points behind a scrim of rhetorical hair-splitting or other pettifoggery. After the Florida Department of Education (possibly the most misleadingly-named government agency in the United States) released a list of 300 books removed from school library shelves in 2022, a spokeswoman for the department declared, “Florida does not ban books.”

Book bans become a front in the partisan culture war

It’s a challenge to parse her statement, since she explained that “the list comprises information provided by each school district of the books they removed based on objections from a parent or resident of the county using their district’s process.” Perhaps she meant to say that Florida does not ban books — Floridians do.

Then there’s Matthew Walther, a Catholic functionary who tried, in a New York Times essay originally titled, “This Is Why I Hate Banned Books Week,” to define opposition to book bans as some sort of performative liberal moralism — “See how brave we are, inviting people to read these daring books!” is how he boorishly characterizes the opposition’s motivation.

(The Times changed the headline, without explanation, to “The Enemies of Literature Are Winning,” which seems to be utterly contrary to the point the author was making.)

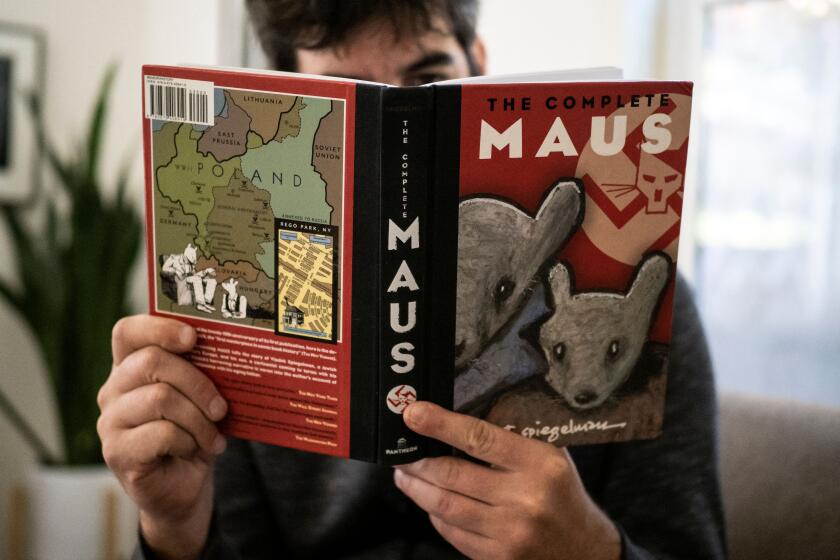

Having named two LGBTQ+-themed books that have risen to the top of the banned-book lists recently, Walther wrote: “In zero cases since the advent of Banned Books Week has a local or state ordinance been passed in this country that forbids the sale or general possession of any of the books in question.”

This is slicing the baloney mighty thin; nor does it say much for the reading comprehension or research skills of Walther or his editors. “Gender Queer” and “Flamer,” the two books he names with LGBTQ+ content, both appear on the Florida list of books forcibly removed from school shelves.

Don’t be fooled by assertions by advocates for bans that they’re only trying to protect children from “pornography” or “inappropriate” content. These terms typically are written into laws or policies without defining them. Notwithstanding Walther’s assertion that no laws or statutes name any of the books removed from shelves, he can’t be unaware that the laws don’t have to name any specific materials for their drafters’ intentions to be crystal clear.

Arkansas Act 372, enacted this year, imposes criminal liability on librarians and booksellers who make “inappropriate” books “accessible” to minors, or in some cases even adults, without defining those terms. A federal judge blocked key provisions of the law in July, calling them “fatally vague.”

The ambiguity is the point, of course. “The incentive it creates for educators is to err on the side of caution by avoiding anything that might be the tripwire,” Nossel says. “Teachers are operating in a climate of intimidation.”

One aspect of book-banning that has remained a constant in recent years is the reactionary partisan program behind it.

The book banners are characteristically Republican rightists or Republican-adjacent. Their goal is to inculcate schoolchildren or their communities with a wholly imaginary picture of a bygone America in which Black or LGBTQ+ people didn’t exist in mainstream society, so their concerns could be safely ignored.

From “PragerU” in the Florida schools to the evisceration of language and humanities courses in West Virginia, the GOP is intent on turning out students who can’t think for themselves.

One trend noticed by free-speech advocates — the real ones fighting book bans, not the fake ones such as Florida’s GOP Gov. Ron DeSantis, a narrow-minded, opportunistic troll who masquerades as a free-speech guardian — is that the traditional model in which individuals targeted an individual title here or there has yielded to armies of activists who come to school district or libraries bearing the names of books by the ream.

In the old days, says Caldwell-Stone, a parent might find his or her child reading a book, look it over, and bring a concern to a teacher or librarian.

“Now we’re seeing groups go to school or library board meetings and demanding the removal of multiple titles all at once — 25, 50, 100 titles or more, often based on lists they get from advocacy groups on social media,” she says.

“It’s not really an authentic parental concern about a book,” she adds, “but an advocacy group going after a set of books that they don’t believe should be available to the public because they disagree with their viewpoint or that highlight the lives or voices of groups that have been systematically marginalized in our society.” Often, the objectors haven’t read the books.

Boards, principals or librarians reasonably concerned about their jobs or careers sense that they have no choice but to capitulate until they have a chance to review every title, which can take many months. In the meantime, the books are inaccessible, which is the banners’ goal.

If there’s a glimmer of hope in this dismal landscape, it’s that judges have been consistently hostile to these campaigns. Rulings have been piling up, especially in federal court, invalidating book bans and ordering challenged material back on the shelves on grounds that their removal violated the 1st Amendment or users’ rights to due process.

In March, a federal judge in Texas ordered a county library board dominated by a hand-picked right-wing cabal to replace 12 books that they had removed from the shelves and from the system’s catalog so patrons would know they were in the library and could find them.

In 2020, another Texas federal judge invalidated an ordinance enacted in the city of Wichita Falls that allowed books to be removed from the public library if petitions with 300 signatures demanded their removal. The city has more than 100,000 residents. The original targets of the rules were the children’s books “Heather Has Two Mommies” and “Daddy’s Roommate,” which depicted families headed by same-sex couples.

In 2003, an Arkansas federal judge invalidated a local school district’s rule that the Harry Potter books could only be lent from the school library to students who presented a written permission slip from a parent; the books had been challenged by a local pastor and his church members for promoting “witchcraft.”

Book banners have turned to taking other steps that may not be reviewable in the courts. A public library in Virginia is facing extinction this year because a small group of activists objecting to LGBTQ+ material on its shelves goaded their county Board of Supervisors to cut off funding that covers 75% of its budget.

A library in rural Michigan has faced the same threat. Taxpayers in its conservative county have twice voted down funding that accounts for 84% of its budget, again over LGBTQ+-themed books. The library has offered to paste descriptions of the books’ content onto their inside covers, hoping that that will mollify residents enough to approve the funding in a November vote.

There are few indications yet that the wave of book bans will ebb any time soon — not until defenders of free speech stand up to defend their school and public libraries against a minority cabal that believes that medieval standards of learning and knowledge should be the model for American society.

Banned Books Week should be a reminder that such notions can only thrive if the rest of us fight against them — and not only for one week every year, but every day and every week.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.