Opinion: How to counter China’s scary use of AI tech

Nowhere is the competition in developing artificial intelligence fiercer than in the accelerating rivalry between the United States and China. At stake in this competition is not just who leads in AI but who sets the rules for how it is used around the world.

China is forging a new model of digital authoritarianism at home and is actively exporting it abroad. It has launched a national-level AI development plan with the intent to be the global leader by 2030. And it is spending billions on AI deployment, training more AI scientists and aggressively courting experts from Silicon Valley.

The United States and other democracies must counter this rising tide of techno-authoritarianism by presenting an alternative vision for how AI should be used that is consistent with democratic values. But China’s authoritarian government has an advantage. It can move faster than democratic governments in establishing rules for AI governance, since it can simply dictate which uses are allowed or banned.

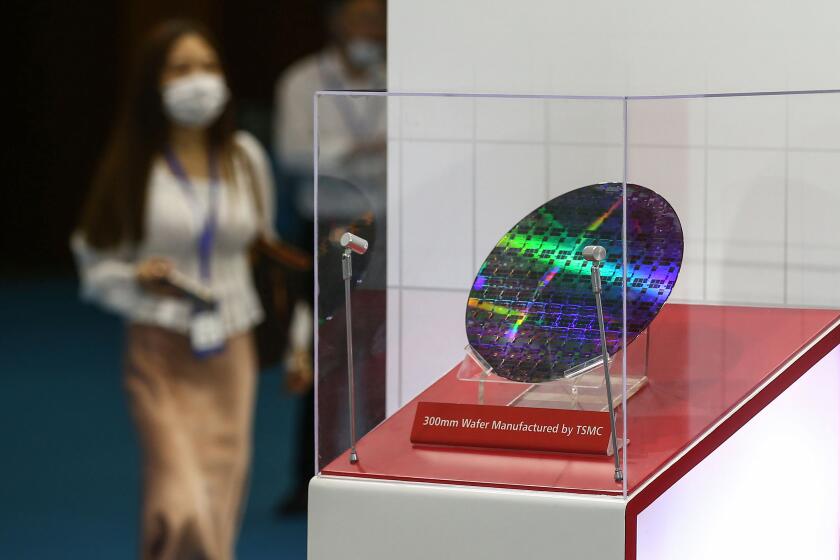

The administration’s new crackdown on China’s chip industry is the only way to stop the country from misusing U.S. tech tools.

One risk is that China’s model for AI use will be adopted in other countries while democracies are still developing an approach more protective of human rights.

The Chinese Communist Party, for example, is integrating AI into surveillance cameras, security checkpoints and police cloud computing centers. As it does so, it can rely on world-class technology companies that work closely with the government. Lin Ji, vice president of iFlytek, one of China’s AI “national team” companies, told me that 50% of its $1 billion in annual revenue came from the Chinese government.

The government is pouring billions of dollars into projects such as the Skynet and Sharp Eyes surveillance networks and a “social credit system,” giving it a much larger role in China’s AI industry than the role the U.S. government has in the industry here.

China is building a burgeoning panopticon, with more than 500 million surveillance cameras deployed nationwide by 2021 — accounting for more than half of the world’s surveillance cameras. Even more significant than government cash buoying the AI industry is the data collected, which AI companies can use to further train and refine their algorithms.

Facial recognition is being widely deployed in China, while a grassroots backlash in the U.S. has slowed deployment. Several U.S. cities and states have banned facial recognition for use by law enforcement. In 2020, Amazon and Microsoft placed a moratorium on selling facial-recognition technology to law enforcement, and IBM canceled its work in the field. These national differences are likely to give Chinese firms a major edge in development of facial-recognition technology.

China’s use of AI in human rights abuses is evident in the repression and persecution of ethnic Uighurs in Xinjiang, through tools such as face, voice and gait recognition. Under the Strike Hard Campaign, the Chinese Communist Party has built thousands of police checkpoints across Xinjiang and deployed 160,000 cameras in the capital, Urumqi. Facial-recognition scanners are deployed at hotels, banks, shopping malls and gas stations. Movement is tightly controlled through ID checkpoints that include face, iris and body scanners. Police match this data against a massive biometric database consisting of fingerprints, blood samples, voice prints, iris scans, facial images and DNA.

The techno-authoritarianism China is pioneering in Xinjiang is being replicated not only across China but around the world. On smaller scales and less effectively, but with increasing proficiency over time, other nations are adopting elements of Chinese-style digital repression. Chinese surveillance and policing technology are now in use in at least 80 countries. And China has held training sessions and seminars with more than 30 countries on cyberspace and information policy.

The problem is not just that AI is being used for human rights abuses but that it can supercharge repression itself, arming the state with vast intelligent surveillance networks to monitor and control the population at a scale and degree of precision that would be impossible with human agents.

In the face of these AI threats, democratic governments and societies need to work to establish global norms for lawful, appropriate and ethical uses of technologies like facial recognition. One of the challenges in doing so is that there is not yet a democratic model for how facial recognition or other AI technologies ought to be employed.

The U.S. government needs to be more proactive in international standard-setting, working with domestic companies to ensure that international AI and data standards protect human rights and individual liberty. International standard-setting — through organizations such as the International Organization for Standardization, the International Electrotechnical Commission and the United Nations International Telecommunication Union — is one of the lower-profile but essential battlegrounds for global tech governance.

AIs can spit out work in the style of any artist they were trained on — eliminating the need for anyone to hire that artist again.

China has been increasingly active in international standard-setting bodies. In 2019, leaked documents from the U.N. telecommunication union’s standards process, which covers 193 member states, showed delegates considering adopting rules for facial recognition that would facilitate Chinese-style norms of surveillance. For example, proposals to store a person’s race in a database could be used for profiling.

In the contest over how AI will be used, democratic nations have many advantages over authoritarian regimes; namely, greater talent, military power and control over critical technologies. Yet these advantages are fragmented among various countries and actors, including governments, corporations, academics and tech workers. The challenge will be harnessing and managing these disparate forces. But the diversity of voices is a great strength in controlling the uses of AI and building a responsible tech system.

AI can be used to bolster individual freedom or crush it. Russian President Vladimir Putin has said about AI: “Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.” The race to lead in AI and write the rules of the next century is underway, and with it, the future of global security.

Paul Scharre is vice president and director of studies at the Center for a New American Security. He is author of the forthcoming book “Four Battlegrounds: Power in the Age of Artificial Intelligence.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.