Op-Ed: What Silicon Valley must sacrifice to curb China’s exploitation of U.S. tech

Previous U.S. administrations have targeted specific Chinese companies accused of supporting China’s defense modernization or violating human rights. Former President Trump, for instance, imposed restrictions on telecommunications equipment-maker Huawei. Now, President Biden is taking on China’s entire computing industry.

The Biden administration announced earlier this month a dramatic expansion of controls on the export of U.S. semiconductor technology to China. The aim is to hobble the most advanced parts of China’s tech sector and partially decouple the two countries’ innovation ecosystems. The move comes after two years of a pandemic-induced global semiconductor shortage as well as a bill that Congress passed in July that will pump $52 billion into initiatives that boost America’s chip industry.

The Biden administration considers further advances in Chinese semiconductor technology — or the artificial intelligence applications that advanced chips enable — counter to U.S. national interests. It’s hard to imagine a more sweeping move against unfettered technological globalization than Biden’s latest action.

With chip production so heavily concentrated in Asia, supply-chain resilience is threatened by mounting geopolitical tensions with China.

The administration took this step because prior U.S. policy wasn’t working. For a decade, the U.S. has failed to stop the flow of computing technology to the Chinese military. It’s comparatively easy to limit technologies like missiles or radars when they have solely a military purpose. Now, though, the critical tech the Chinese want — high-tech chips and the advanced computing they support — is used in both military and civilian applications.

The U.S. had tried to stop certain Chinese firms with military links from accessing advanced chips, while letting tech flow to commercially oriented firms. But that policy clearly left gaps: Open-source studies found numerous instances of U.S. chips being used to support the Chinese military. The new U.S. strategy — cutting off all of China, not just defense firms — is the only effective way to stop U.S. tech from aiding the Chinese military.

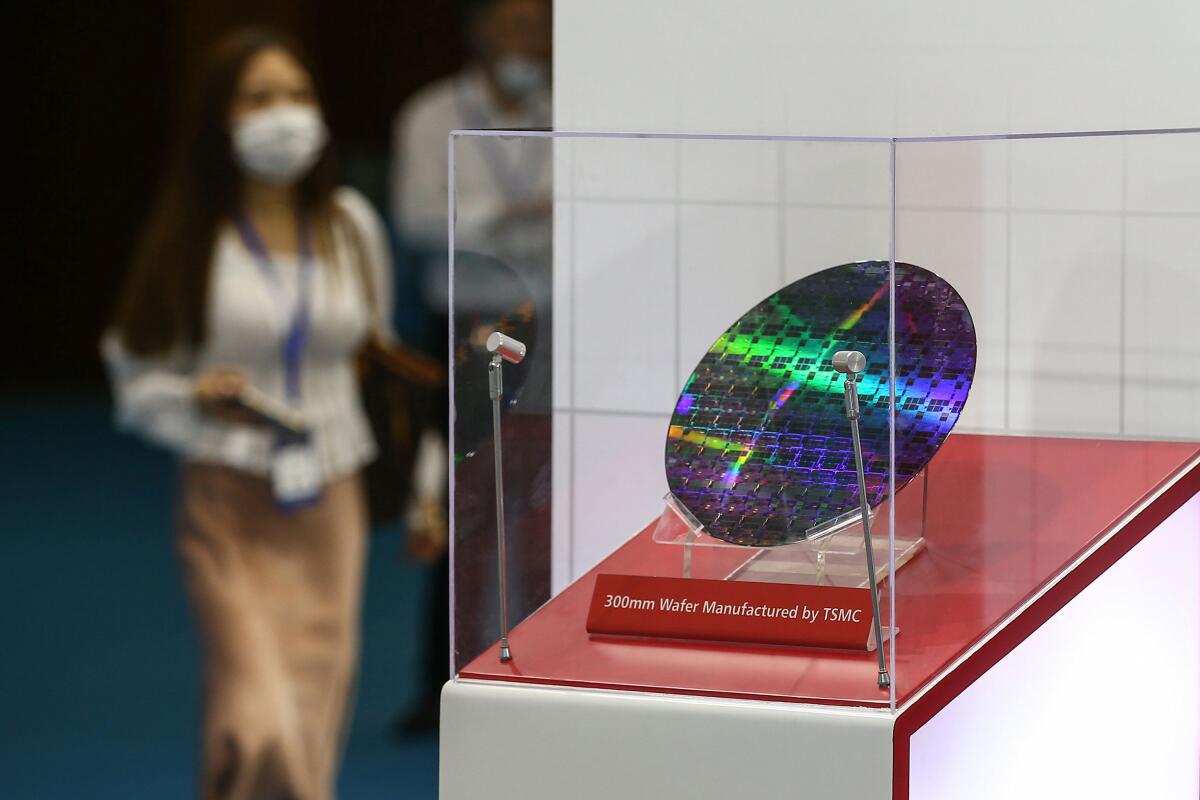

As part of the new strategy, the Biden administration has placed new controls not merely on specific Chinese firms, but on the whole country. These regulations limit the transfer of cutting-edge graphics processing units, known as GPUs, a type of chip that is critical to running artificial intelligence applications in data centers. NVIDIA and AMD, both based in Santa Clara, currently monopolize the design of advanced GPUs. They outsource the production of these chips to the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., the world’s most advanced chip manufacturer. The new U.S. regulations make it illegal to transfer these chips from Taiwan to China without a license.

These rules intend to slow advances in high-performance computing in China. Supercomputers have multiple uses, from mapping weather patterns to modeling nuclear explosions. The U.S. government is skeptical about selling advanced chips to China for civilian purposes because despite substantial earlier efforts to stop sales of chips to the Chinese military, once chips enter China, the U.S has no control over where they end up.

For the U.S. tech industry, the most disruptive restriction will be the new limits on the ability of American citizens and companies to interact with a broad array of Chinese chip firms. U.S. citizens have often been legally engaged with Chinese chip firms, servicing their machines, selling them materials or in some cases, even working as chief executive officers. Now, Americans face legal penalties for conducting business with a swath of Chinese firms, just as they would with sanctioned companies from Iran or North Korea.

Globalization interwove economies of very different nations, now coming apart as autocracies ally with the Kremlin and democracies stand with Ukraine.

The effects of these sanctions will be substantial. The lives of American workers currently in business with relevant Chinese chip firms will be upended. U.S. companies, too, are feeling the heat. AMD and NVIDIA saw their stock prices slump after Biden’s moves, as investors counted the cost of lost sales to China. Similarly, American manufacturers of chipmaking machinery will lose sales, too, because some Chinese facilities will be forced to close shop and cancel orders. These companies all make most of their revenue outside of China, but the lost revenue will still sting.

American buyers of Chinese chips will also be hit. One of the most notable examples is Apple Inc., which was planning to use chips from China’s government-backed chipmaker Yangtze Memory Technologies Co. in new iPhones. Now Apple is reportedly changing tack and will have to buy chips from non-Chinese companies at market prices, rather than the subsidized rates Yangtze Memory Technologies would have been able to offer.

Despite the pinch Silicon Valley companies will feel, China faces a much bigger adjustment. It will take China’s chip firms at least a decade to develop advanced chipmaking capabilities at home — if they ever succeed. Meanwhile, China’s government and tech companies must adjust to a future without access to advanced computing hardware.

The idea that Chinese chip firms could be listed alongside Iranian missile designers or North Korean nuclear scientists as foreign policy threats will surprise many Americans. Yet when it comes to advanced chips and the computing power they enable, the line between civilian and military technology is difficult to distinguish and impossible to police. Deep interconnections between the U.S. and Chinese businesses had left it easy for the Chinese military to acquire U.S. tech. The Biden administration’s new restrictions on China’s chip sector may finally succeed in closing this loophole.

Christopher Miller is a professor at the Fletcher School, visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and author of the book “Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.