Column: Business is the most trusted institution? Are you kidding me?

You’d think that people would have learned their lesson after years of financial industry gimmickry, corporate tax avoidance and mistreatment of workers.

You’d think they’d get wise when they see companies moving their business off shore and stashing profits overseas. Or when corporations engage in mass layoffs during tough times while paying exorbitant salaries and bonuses to top executives. Or when business interests fight against raising the minimum wage, try to keep out unions or fail to improve unsafe working conditions.

But no. Despite the evidence before their eyes, most people around the world and in the United States still trust business to “do what is right” more than they trust other big institutional sectors.

Opinion Columnist

Nicholas Goldberg

Nicholas Goldberg served 11 years as editor of the editorial page and is a former editor of the Op-Ed page and Sunday Opinion section.

That’s the key finding in a report by the giant public relations firm Edelman, released earlier this month to coincide with the gathering of the world’s power brokers and tycoons at Davos: People in the 28 countries surveyed say they trust business to do the right thing more than media, government or non-governmental organizations.

They rate business more highly than those other institutions for competency, which might be justifiable. But business also outscores government by 30 points on ethics.

What? How can that be? But it’s true — globally and in the United States, where 55% of respondents said they trust business to do what is right, as compared to 50% for NGOs, 43% for media and 42% for government.

Now I don’t want to suggest that everyone in business is corrupt or untrustworthy or that the capitalist system should be dismantled tomorrow. But to single out business as the most trustworthy institution strikes me as simply bizarre.

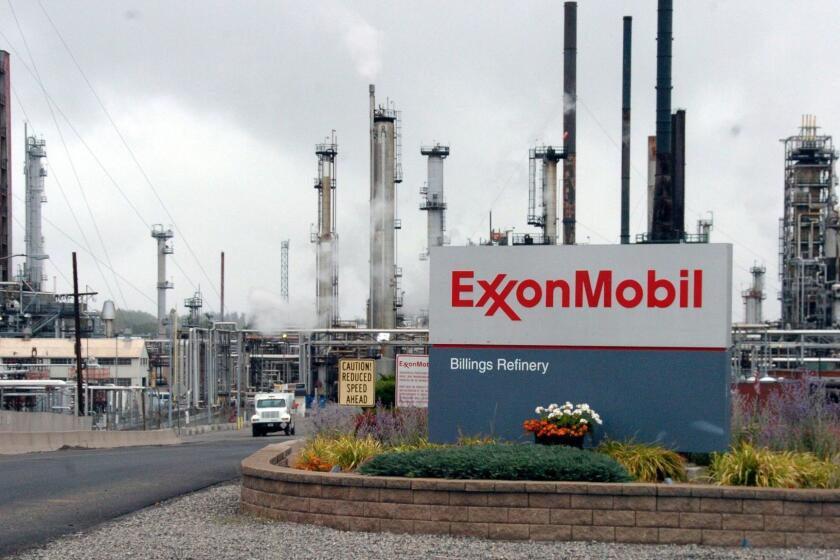

A new report details how Exxon Mobil and the fossil fuel industry, over decades, worked to deceive the public over the science of climate change and avoid regulation.

Consider this story in The Times, also published earlier this month. It began:

“In perhaps the most unexpected twist in the field of climate science, new research suggests Exxon Mobil Corp. had keener insight into the impending dangers of global warming than even NASA experts but still waged a decades-long campaign to discredit the science on climate change and its connection to the burning of fossil fuels.”

That doesn’t make Exxon Mobil sound very trustworthy to me. And despite what the article says, it’s not very “unexpected” either.

It’s not unexpected because, as the story notes, we’ve already known from a “growing body of evidence” that Exxon Mobil recognized decades ago, in the late 1970s, that burning fossil fuels was warming the Earth “even as it continued to heap doubt onto that notion publicly.”

But it’s also not unexpected because this kind of deception by corporations is all too common.

Tobacco companies spent decades suppressing the evidence and discrediting the science that showed links between smoking and cancer, though the companies knew the link was real. Meanwhile, millions died prematurely from smoking-related disease.

Opioid makers spent years promoting their habit-forming pain medications to healthcare providers they knew were prescribing them for unsafe and ineffective purposes, contributing to a national tragedy of addiction — but driving up profits to staggering levels.

Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta claims Exxon Mobil and other corporations have perpetuated the ‘myth’ that recycling will solve the plastics crisis.

The financial services industry engaged in abusive, self-serving mortgage practices, including giving out risky loans — causing ruinous harm to ordinary Americans hoping to buy homes and helping ignite a global recession.

Pharma companies, big food producers, gun manufacturers — all have misled their customers at one point or another. It’s not aberrant behavior by a few bad apples; it’s companies doing what the market incentivizes them to do.

Corporations don’t exist to make the world a better place or even to provide customers with the goods and services they need. Rather, the overarching goal is to maximize profits. And sometimes that requires being less than honest, in the view of some executives.

Sure, some company employees might push back and some whistleblowers might emerge, but they’ll only win some of the time.

I’m not arguing that people should place all their trust in government instead. It’s hard to trust politicians when people like George Santos are kicking around the Capitol. And when the Washington Post cataloged more than 30,000 lies by President Trump during his four-year tenure. And when three members of Los Angeles City Council have in the past few years been indicted, pleaded guilty or served time.

But NGOs? What have NGOs ever done wrong that compares with the misbehavior of corporations? (To their credit, respondents to the survey gave high trust rankings to scientists, higher than they gave to CEOs.)

That’s the only reliable way to marshal insiders as corporate watchdogs.

I assume that, in the U.S. anyway, the relatively high trust people place in business is the result, at least partly, of the persistent power of the classic American dream — the increasingly archaic belief that anyone who works hard and plays by the rules of our free-market, business-friendly society can rise up the ladder from poverty to affluence.

The sad fact, though, is that we live in an America where upward mobility is no longer the rule.

I’m no Marxist. I believe capitalism has plenty of advantages over the alternatives.

But it’s a mistake to believe that corporate interests are aligned with our own. What’s good for General Motors is not necessarily good for the country. We want the jobs that business provides and the goods it produces and certainly we want a healthy, vibrant, dynamic economy. But corporations need to be regulated and monitored if they’re going to do what is right.

And while we work to hold them accountable, the last thing we should do is trust them blindly.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.