Exxon Mobil publicly denied global warming for years but quietly predicted it

In perhaps the most unexpected twist in the field of climate science, new research suggests Exxon Mobil Corp. had keener insight into the impending dangers of global warming than even NASA experts but still waged a decades-long campaign to discredit the science on climate change and its connection to the burning of fossil fuels.

Despite its public denials, the major oil corporation worked behind closed doors to carry out an astonishingly accurate series of global warming projections between 1977 and 2003, according to a study published Thursday in Science.

“Exxon didn’t just know some climate science, they actually helped advance it,” said Geoffrey Supran, lead author of the study and former researcher in the department of the history of science at Harvard University. “They didn’t just vaguely know something about global warming decades ago, they knew as much as independent academics and government scientists did. And arguably, they knew all they needed to know.”

In a review of archived documents and memos, researchers found that scientists for then-Exxon had completed a set of 16 models that predicted global temperatures would rise, on average, about 0.36 degrees Fahrenheit (0.2 degrees Celsius) per decade. Since 1981, Earth’s global average temperature has risen about 0.32 degrees (0.18 Celsius) per decade, according to NASA.

The California Air Resources Board has released its long-awaited scoping plan, a roadmap for the state to drastically cut its carbon emissions.

Researchers at Harvard and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research found most of the Exxon Mobil projections are consistent with subsequent global temperature observations, according to the study. Many of the Exxon projections proved to be more precise than those by James Hansen, then-director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, who famously testified before the U.S. Senate in 1988 about the greenhouse effect.

The analysis adds to a growing body of evidence that the nation’s largest oil producer recognized burning fossil fuels was warming the Earth, even as it continued to heap doubt onto that notion publicly. The paper also shows, for the first time, just how precise and sophisticated the fossil fuel industry’s own climate research was.

In response to the study, Exxon Mobil spokesperson Todd Spitler said the company’s understanding of climate science has evolved along with that of the broader scientific community. The energy company, he said, is now actively engaged on several efforts to mitigate global warming.

“This issue has come up several times in recent years and, in each case, our answer is the same: those who suggest ‘we knew’ are wrong,” Spitler said in a statement. “Some have sought to misrepresent facts and Exxon Mobil’s position on climate science, and its support for effective policy solutions, by recasting well intended, internal policy debates as an attempted company disinformation campaign.”

The Harvard-led study builds on previous academic research, in addition to investigative reporting by Inside Climate News and the Los Angeles Times, that uncovered a tranche of internal company memos demonstrating Exxon officials have known since the late 1970s that burning fossil fuels would lead to global warming.

Exxon was a pioneer in the arena of climate research in the early 1980s. But its public stance on global warming had changed sharply by 1990.

As wildfires become more extreme, some worry California will near a tipping point in which its forests emit more carbon dioxide than they absorb.

In one internal draft memo from August 1988 titled “The Greenhouse Effect,” a public relations manager detailed the scientific consensus about the role of fossil fuels in global warming but wrote that the company should “Emphasize the uncertainty.” An archived presentation in 1989 from Exxon’s manager of science and strategy development said: “Data confirm that greenhouse gases are increasing in the atmosphere. Fossil fuels contribute most of the CO2.”

In 1999 — the year Exxon and Mobil merged — company Chief Executive Lee Raymond, however, said future climate “projections are based on completely unproven climate models, or, more often, sheer speculation.”

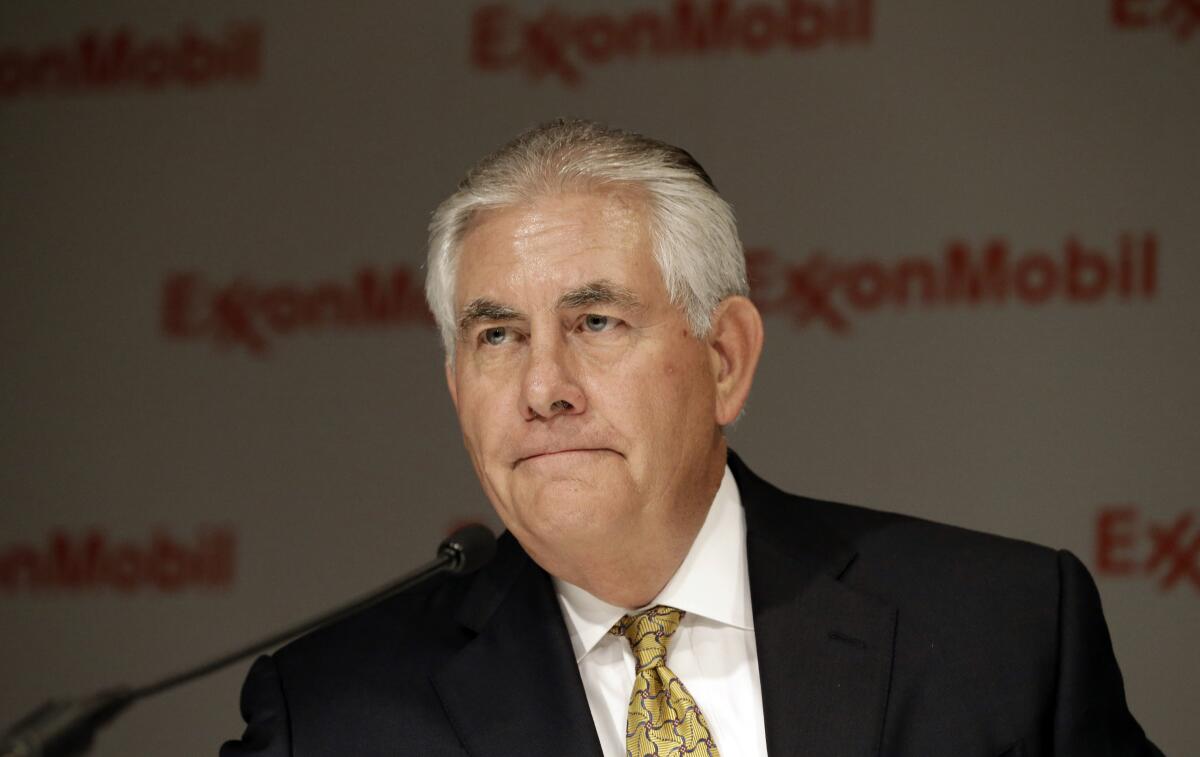

In 2015, Raymond’s successor, Rex Tillerson, who later served as secretary of State under President Trump, also questioned climate projections involving the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

“We do not really know what the climate effects of 600 parts per million versus 450 parts per million will be because the models simply are not that good,” Tillerson said.

However, Exxon’s own modeling from 1982 suggested that 600 ppm of CO2 would lead to 2.3 degrees (1.3 Celsius) more global warming than 450 ppm.

The analysis also found that Exxon scientists had projected that global warming would first become detectable at the turn of the 21st century. The Exxon scientists concluded this warming trend would render the Earth hotter than at any time in at least 150,000 years, debunking unfounded theories of “global cooling” and a forthcoming ice age.

Despite such findings by their own scientists, company officials poured millions of dollars into a public relations campaign to cast doubt on the science behind climate change. That campaign included prominent ads in the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times.

“They were right on the money in terms of rejecting a possible ice age, accurately predicting when warming would first be detectable, estimating the carbon budget for 2 degrees [Celsius] — and then, in all of those points, the company’s subsequent public statements contradicted its own data,” said Supran, now an associate professor of environmental science and policy at the University of Miami.

It wasn’t until 2007 that Exxon Mobil publicly acknowledged that climate change was occurring and that it was largely driven by the burning of fossil fuels and proliferation of heat-trapping CO2.

Southern California has long struggled to meet federal air pollution standards. Now, the EPA wants to impose even higher requirements for particulate matter.

Before the Industrial Revolution, CO2 levels were consistently around 280 ppm for almost 6,000 years of human civilization, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Since then, humans have released an estimated 1.5 trillion tons of carbon emissions through the burning of fossil fuels, including natural gas, coal and methane.

In 2022 — which NOAA now ranks as the sixth-warmest year on record — CO2 levels reached 420 parts per million in November, a mark the planet hasn’t seen in millions of years.

Nine of the last 10 years have been the warmest since 1880, according to NOAA. These rising temperatures are fueling extreme weather events worldwide, and California and the western U.S. have been on the frontlines in recent years.

Despite a recent barrage of deadly storms that have hit California since the beginning of the year, the American Southwest is still braving one of its driest stretches in 1,200 years. California is also still recovering from a record-setting wildfire season in 2020, during which 4.3 million acres were scorched statewide. And as Arctic ice continues to melt, sea level rise threatens to exacerbate coastal erosion.

The recent findings regarding Exxon Mobil studies have given more fodder to #ExxonKnew — an environmental campaign that traces its origins to a 2012 meeting of climate activists and experts in La Jolla. Its supporters have accused Exxon Mobil of intentionally misleading the public and causing humanity to lose precious time in the fight to curtail carbon emissions. They have called for investigations into the company’s statements about climate change and fossil fuels.

Dozens of local and state governments, including several California cities, have filed suit against Exxon Mobil and other energy companies for orchestrating public deception campaigns in spite of internal scientific knowledge.

In 2019, a state judge dismissed the New York attorney general’s lawsuit against Exxon Mobil that accused the company of defrauding its shareholders by failing to accurately account for the risks of climate change.

As Exxon Mobil continues to challenge similar litigation elsewhere, the company’s website is now chock-full of climate-friendly lingo on how it intends to support a “net-zero future” with “lower-emission efforts” — a stark departure from its public stance more than a decade earlier.

“There’s this sort of gradual evolution away from outright denial and towards what we call discourses of delay,” Supran said. “That kind of blends into the present where we have these much more subtle discourses that position fossil fuels as essential to the future of humanity.”