Op-Ed: It’s a crucial charter-conventional school clash: Baldwin Hills Elementary wants its campus back

By now everyone knows there’s bad blood between conventional schools and charters. It’s permanent family dysfunction rooted in the fact that they’re related — charters are quasi-public schools that operate with fiscal independence and less oversight than their traditional counterparts. But from the beginning, marked differences in funding and educational philosophy have put them in opposing camps.

Over the last 20 years, charters encroached on conventional schools’ turf literally as well as figuratively, thanks in part to Proposition 39, which requires school districts to rent empty space on their campuses to charters.

“Colocation” is the somewhat bland term for an inherently tense roommate situation that’s been aggravated by the pandemic, which decimated school attendance and increased real estate prices, prompting charters to lean more than ever on school districts for facilities, and to sue to get their due.

The warfare can at times seem abstract, a legalistic debate about which system is entitled to what resources. But every so often, a shared-turf battle punches through the noise and illustrates exactly what the colocation stakes are for students and their educational future.

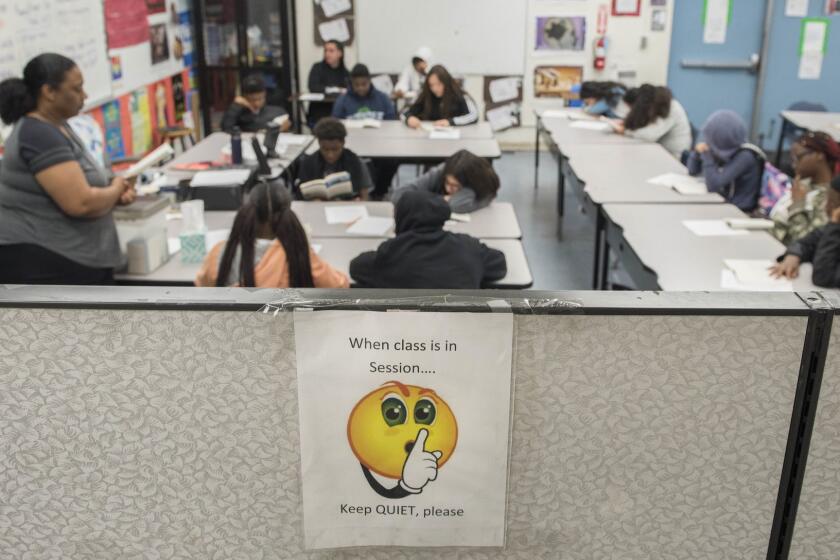

The eighth-grade English class at Magnolia Science Academy 3 met last semester in an unusual setting: a carved-out rectangle in the school’s office, formed by portable dividers.

One such fight is coming to a head in Los Angeles. It’s forcing a question: Will the Los Angeles Unified School District find a way to support — even magnify — that rarest of success stories: a high achieving predominantly Black neighborhood school?

For the last seven years, Baldwin Hills Elementary School, a nearly 80-year-old campus in the Crenshaw district, has had to share digs with a charter, New Los Angeles Elementary.

New L.A. has about 200 students; Baldwin Hills twice that, but the neighborhood school’s sense of infringement isn’t just about the comparative sizes of the two student bodies.

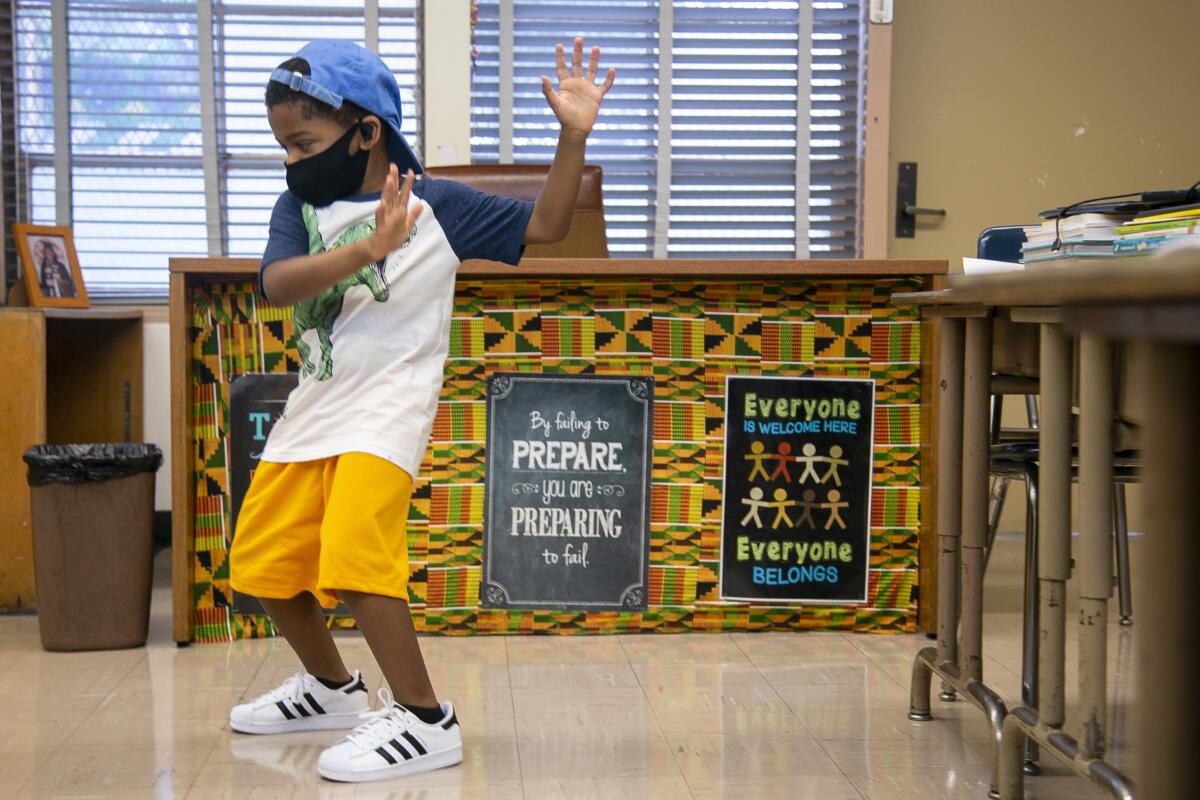

BHE features ambitious programs. It houses a gifted magnet and serves as a “community school,” with “wraparound” healthcare and family support services. It’s also a so-called pilot school, which gives it the autonomy to offer unique classes such yoga, chess and orchestra. And it’s a designated STEAM campus — science, technology, engineering, the arts and math. In 2020, the state Department of Education designated Baldwin Hills, where 82% of the student body is Black, a distinguished school.

California is home to about one out of every five charter schools in the United States, but state oversight of them is far from a national model.

Not surprisingly, BHE parents and teachers tend to be organized, involved and deeply committed to growing what is regarded as an unqualified school success. To do that, they say, the school needs to get back space that was deemed nonessential and ceded to New L.A.: The charter, they say, must be relocated.

Back in October, members of Neighbors in Action for Baldwin Hills Elementary, a BHE parent-community-teacher coalition, sent a letter to LAUSD outlining their colocation complaints.

Sharing the campus, they wrote, “has greatly diminished the school’s ability to meet students’ social-emotional needs and mental health wellness, and hampered access to the academic programs that the school has been tasked with providing.”

Because of space constraints, Baldwin Hills is out a computer and robotics lab. Orchestra classes have been conducted on the playground blacktop. Students have to eat lunch hurriedly in a time-shared cafeteria. The bathrooms are overcrowded and sometimes unsafe.

In short, Baldwin Hills is an unfolding success story, in spite of colocation. “If we can do this in a stifled environment, imagine what we could do in a regular environment,” says Love Collins, a parent who switched her third-grader from a private school to Baldwin Hills.

The BHE coalition insists the district could find a way within the rules to relocate New L.A. (For it’s part, New L.A. claims to be looking elsewhere for a “permanent” school site.)

Urban classrooms are already vulnerable. As enrollment diminishes, so do the promise and ambition of public education in L.A.

Community schools, for example, are supposed to be exempt from colocation, a rule the parents believe should apply at BHE despite the fact that Baldwin Hills wasn’t designated a community school until after New L.A. had moved in.

It’s a point that feels strengthened by recent developments. Two years ago, a new state law, AB 1505, gave school districts — charter school “authorizers” — expanded criteria in deciding whether to deny space to new charters or renew the leases of existing ones.

So far, LAUSD’s response has been underwhelming. Half a dozen district representatives came to Baldwin Hills for a town hall after the October letter, but as a second letter the coalition organizers sent to the district points out, none of their specific complaints or proposed solutions were addressed.

For months, the BHE group has solicited the support — or simply a call-back — from their LAUSD District 1 board member, George McKenna. When he was principal at Washington Prep, McKenna had a well-earned reputation for advocating for students of color and instituting a culture of high expectation. But neither he nor his staff has met with Neighbors in Action for Baldwin Hills Elementary.

“I very much support the parents and programs at Baldwin Hills Elementary, and always have,” McKenna says. “It’s a wonderful school.” What he doesn’t say is anything about the colocation conflict.

But the coalition is not scaling back the pressure for more definitive support.

“All we’re asking district to do is find another place to house [New L.A.], and don’t renew their contract at Baldwin,” says Jacquelyn Walker, a longtime teacher at Baldwin Hills who became its community school coordinator last year.

Underlying the many practical arguments here is a philosophical one: If Black lives truly matter, Baldwin Hills deserves — is, in fact, entitled to — as much space as possible.

With BHE, LAUSD has an organic model of Black success that the district should be nurturing, not stunting. In Walker’s words: “Allow us to thrive, give us the opportunity to do what we can do.”

The stakes for students of color are simply too high to do anything less.

Erin Aubry Kaplan is a contributing writer to Opinion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.