Op-Ed: What happens when public schools lose students?

During all the disruptions of the last two years, walking — one of the few public activities that’s stayed COVID-proof — was absolutely essential. Taking the dogs out into my southeast Inglewood neighborhood, I was on a daily mission to maintain routine in the face of chaos, and also to do rounds, to check on the neighborhood and see how it was holding up.

In the eerie stillness, I was always reassured by the sight of my local elementary school, Century Park. Sprawling but homey, the school was a touchstone of normality, a reminder of Inglewood’s ambition and promise. During the worst of COVID, Century Park was empty, of course, but it was simply on pause, like everything else. I thought of its stillness as an extended summer break that would yield to the hive-like bustle of students again — it was just a matter of time.

I was wrong. A year into the reopening of schools, Century Park is not exactly empty, but it’s notably unfilled. The electronic sign in front flashes an invitation — more like a plea — to enroll, like a longtime business that’s lost its cachet. The large, grassy playing field and the handball courts look bleak, at a loss. What I see now when I walk by is not so much promise as potential ruin. It’s disquieting, like the growing anxiety I feel about climate change. I think: Can we pull back from disaster?

Not that I was completely at ease about the schools before the pandemic — far from it. Majority Black and brown schools like those in Inglewood have been struggling for decades, ever since white flight began eroding the very notion of public schools as sites of achievement and excellence for everyone who showed up. White abandonment led to decline that’s become its own kind of normal. Despite this, I remained a firm believer in public education and the power of schools to effect change, to refute the racial odds and fulfill our democracy’s social contract of justice for all. There was always hope, as long as there were students.

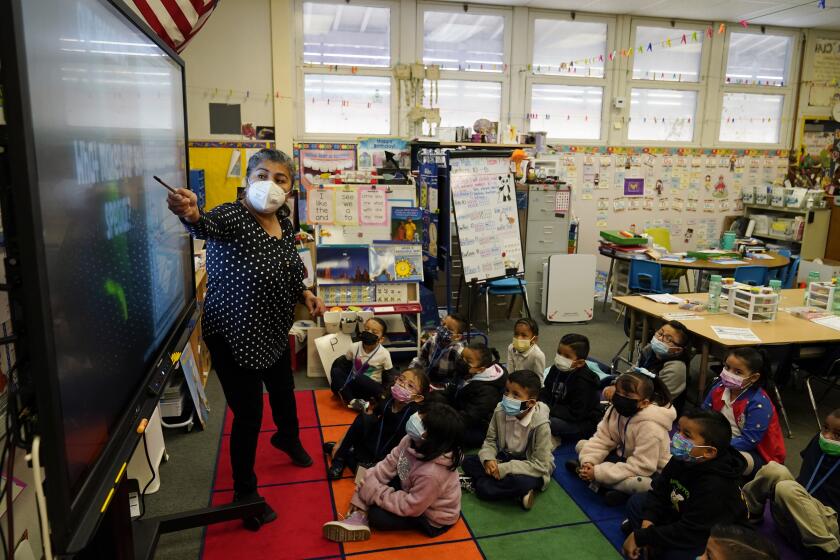

No grade suffered more enrollment drop than kindergarten during the pandemic. Proponents say mandatory enrollment is a solution. Newsom disagrees.

Now with the presence of students in question, and the singular promise of schools dwindling, I wonder, can a neighborhood — or a city — thrive if its schools are disappearing in front of its eyes?

The failure of students to return to school post-COVID — a phenomenon that remains something of a mystery — adds insult to all the injuries suffered by public education. Well before the pandemic, Inglewood’s school district was losing students at an astonishing rate — 500 a year. That wasn’t helped by financial woes (tied to the swooning enrollment) that led to a state and then a county takeover a decade ago. (We still don’t have local control, which many Inglewood residents believe is the most immediate reason for our ongoing attendance crisis.)

Though located in Inglewood, Century Park is actually in the Los Angeles Unified School District, which is also bleeding students. Alberto Carvalho, the new LAUSD superintendent, cites a host of reasons for the decline in enrollment — outmigration from the city, low birthrates, fewer immigrants. Add to that competition from charters and private schools, and the nation’s second biggest district, once about 750,000 strong, has drifted to less than 500,000. And so the ground that public schools have been losing for a long time feels like it’s giving away beneath our feet, with no clear remedy in sight.

Large urban districts, including L.A. Unified, accounted for about one-third of the decline.

While there’s lots of blame to go around, it’s important to remember that at the root of all the erosion is our failure as a nation to meet the challenge of Brown vs. Board of Education, the Supreme Court decision that ordered the desegregation of public schools nearly 70 years ago. Instead of serving as models of integration, urban schools became monuments to that failure: Forsaken by white people, they became synonymous with the Black and brown students who stayed, and with everything associated with the most at-risk among them — poverty, low test scores, behavior problems. The whole mission of public education downshifted from academic achievement to crisis management for sites now populated by students many people regarded as ‘‘other.’’

I know something about this firsthand. In 1972 I was bused out of my South-Central neighborhood to a white elementary school in Westchester several miles away, for a gifted program not available at my neighborhood school. It was not without racial and social tensions, but I did fine academically, as did many other bused-in Black students. This early attempt to equalize schools via a program for students with clear promise was in many ways a success.

But it didn’t matter. Throughout the 1970s, Westchester’s white residents fled their schools, to the point that Westchester High became one of LAUSD’s few primarily Black campuses, even though few Black families lived in the area. Whatever the actual quality of the education, we’d so racialized the idea of good schools — not to mention good neighborhoods — that “primarily Black” denoted “less than.” The campus became a science magnet some years ago to attract, or re-attract, locals, but it remains overwhelmingly African American.

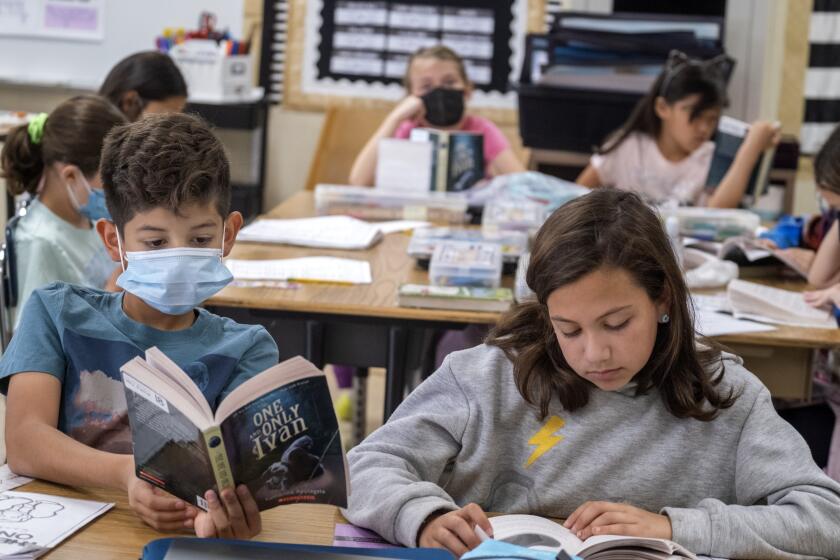

Four more school days, expanded transition kindergarten, better transportation offerings and ‘career labs’ are part of Carvalho’s plan.

Westchester residents may think the quality of their neighborhood today, with its leafy, hilly streets and million-dollar-plus homes, has been untouched by, and uninvolved with, the changed demographic of the local schools. But the disconnect hollows out the community, which by its own hand has cut away something foundational. If Westchester High isn’t excellent, neither is Westchester.

Among many harsh truths that the pandemic forced to the surface is that the very notion of societal goods that we all support and benefit from — including public schools — is vulnerable.

One point of public education is that, the lack of integration notwithstanding, we are all in it together. Perhaps that’s the good news — wherever we live, we are endangered when local schools are endangered. In that real if mostly unacknowledged equality, there is at least some hope for change.

Erin Aubry Kaplan is a contributing writer to Opinion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.