Op-Ed: Why we’re drowning in a ‘tsunami’ of government secrets

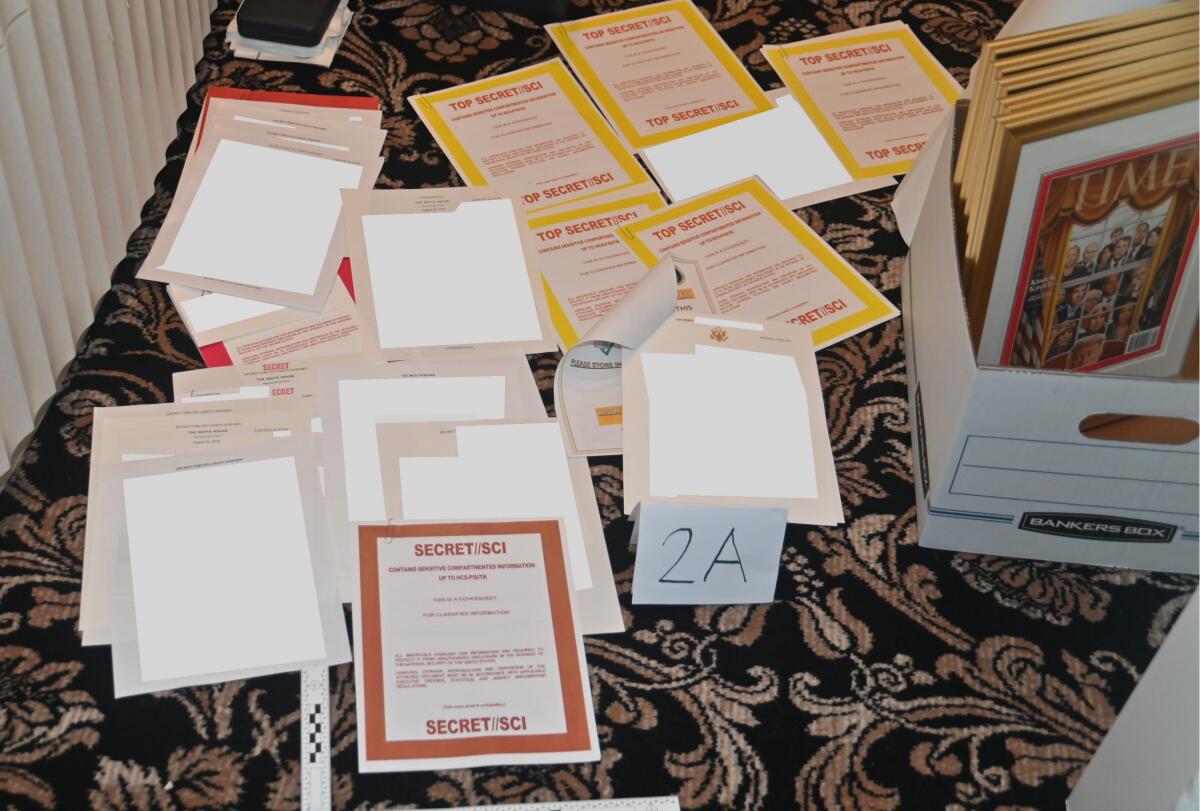

While the eyes of journalists, Congress and the public are on the Department of Justice investigation of the classified documents that former President Trump removed from the White House, a recent report about a different critical issue of government secrecy has gone unnoticed.

This report was given to the Biden administration on July 26 and was written by Mark Bradley, director of the National Archives’ Information Security Oversight Office, which is responsible for overseeing the safeguarding of critical classified information. The report warns of a “dire need” to reform the current system of classification and declassification — cautioning that secrecy itself is out of control. Government officials are classifying so much that it is becoming impossible to prioritize and protect truly sensitive information, much less review classified records so they can eventually be released to the public. “We can no longer keep our heads above the tsunami,” wrote Bradley in his letter introducing the ISOO’s annual report.

The security classification system is designed to control information according to its level of sensitivity, ranging from confidential to top secret. Anyone seeking a security clearance to handle these materials must undergo rigorous background checks and training. But being approved for a level of clearance does not automatically give one access to classified information. Only those who already have access to a specific program’s information can grant others with clearance permission to see it, and only if the requestor has an explicit reason for their “need to know.” The system creates the impression that only a select few are permitted to handle carefully defined categories of truly dangerous information.

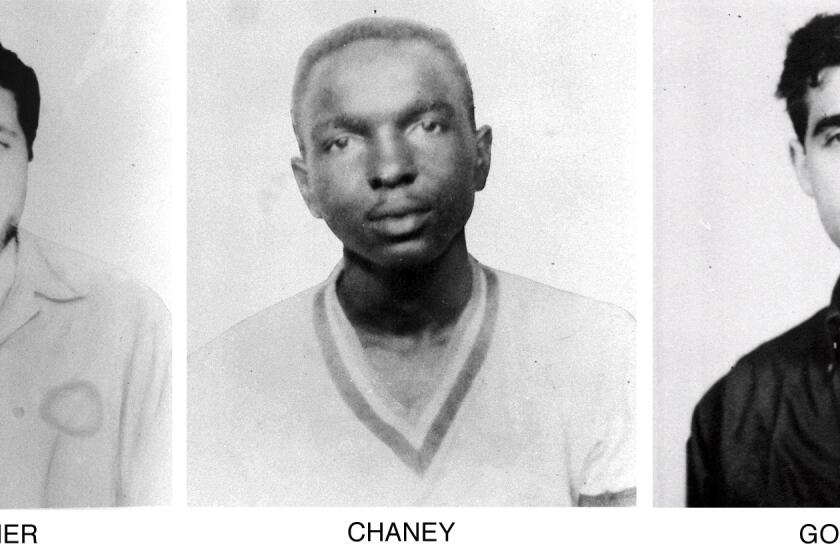

Prosecutions are becoming more difficult in these decades-old murders. But history hasn’t finished with them. Now journalists, scholars and the public need to see the files.

But these rules do not describe what is actually happening. In 2017 alone, officials told the ISOO that they had stamped something with “confidential,” “secret” or “top secret” more than 49 million times. At the time, this seemed like an improvement. In 2012, similar self-reported data added up to more than 95 million classifications, or three new state secrets per second. Bradley now says that a lot of the data in these earlier reports “was neither accurate nor reliable,” but cannot offer better estimates. And so many Special Access Programs — which may require additional security measures and bear the designation “Sensitive Compartmented Information” — have proliferated across the government that Bradley could not create a complete list.

The ISOO report warns that excessive secrecy and underinvestment in declassification is contributing to a lack of trust in government, which recent polls show is nearing historic lows. The number of people who currently have some level of government security clearance to access classified information totals nearly 3 million.

Trump has claimed that he had a standing order to declassify the records that ended up in Mar-a-Lago — but there is no evidence of such an order and numerous officials have called this claim ludicrous. The fact is, the declassification of even one document involves a page-by-page inspection, and often requires sign-off by multiple departments and agencies. Yet the government employs fewer than 2,000 people to review, redact and determine which of these records can eventually be released.

Trump’s handling of sensitive government property is a stunning example of a Trumpian sin: Equating his personal interest with the national interest.

Since World War II, in the earliest days of the current security classification system, some information has been kept secret simply to cover up incompetence. For instance, in 1948 the first chair of the Atomic Energy Commission, David Lilienthal, was appalled by the “lack of integrity” in how officials pretended the “meager” intelligence they had on the Soviet nuclear program was too deep and too delicate to share with Congress. Yet nearly 75 years later, this intelligence is still top secret.

Some officials admit overclassification is endemic but insist that what they give presidents is always sensitive. But even former presidents have said this isn’t the case. George W. Bush started receiving briefings from the CIA at his Texas ranch while the outcome of the 2000 election was still in doubt. After almost a month, Bush suspected the CIA was holding out on him. “I’m sure that when I become president, you’ll start giving me the good stuff,” he said. But the briefer knew the president-elect would be disappointed — “We’ve already been giving him the good stuff,” the briefer thought.

Harry Truman estimated that 95% of American military secrets were actually revealed in the media. Richard Nixon complained, “The CIA tells me nothing I don’t read three days earlier in the New York Times.” Howard Baker, the long-serving senator and Ronald Reagan’s chief of staff, said that, during his entire career, he only learned one secret that remained so.

But many with security clearances tend to only pay attention to classified information related to their specific duties and are unaware of how much of it is already public knowledge.

Some classified information is truly sensitive. But if so much is treated as secret, the public cannot know what government officials are doing in our name. When historians look back at this time, they should read the ISOO report to comprehend the scale of classified information that they likely won’t be able to see. Bradley predicts that so much has been hidden “most of it will never be reviewed for declassification.” It is our history that is being shrouded in secrecy.

Matthew Connelly is a professor of history at Columbia University and author of the forthcoming book “The Declassification Engine: What History Reveals about America’s Top Secrets.” @mattspast

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.