Column: Here’s what happens next for unsolved ‘cold case’ killings from the civil rights era

An aging ex-Klansman once said something to me that I found very disturbing, that colored my view of history forever after.

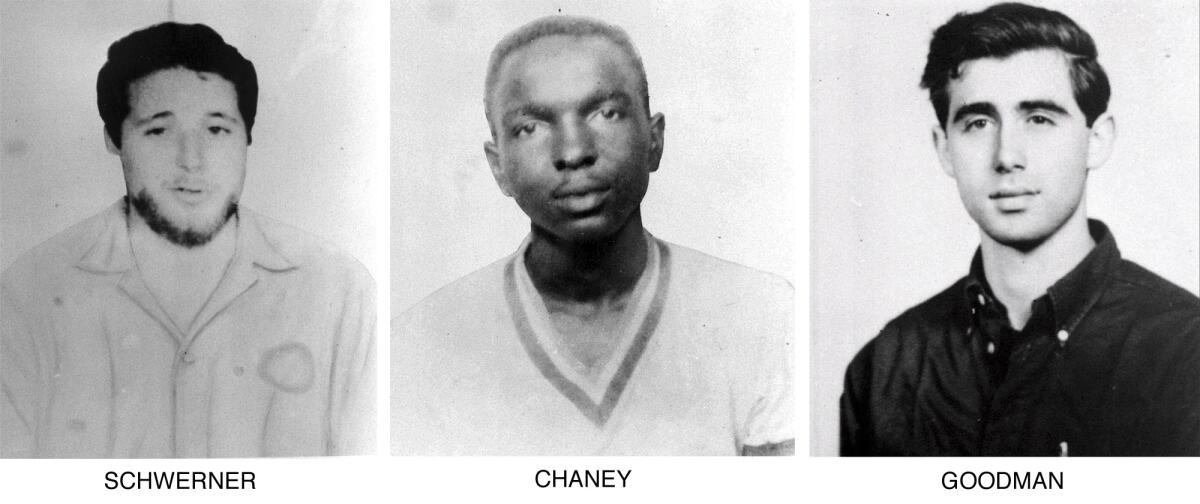

I was working on a story in Philadelphia, Miss., that dealt in part with the deaths many years earlier of three civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Mickey Schwerner. I knocked on the door of Cecil Price, the deputy sheriff and Klan member who had arrested the three young men in June 1964 and then delivered them into the hands of his fellow Klansmen to be murdered in the dark.

Price had served a ludicrously short 4 1/2 years in prison, and he was living comfortably back in his hometown with his wife and son. He was a member in good standing of the local country club.

He chatted briefly, but when I asked him about the killings he gave me an affable half-smile and said, just before shutting the door, “Oh, let’s just let bygones be bygones, why don’t we.”

He said it innocently enough, but I knew how disingenuous his words were. Though nearly a quarter-century had passed, the deaths of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner were not bygones. In fact, it would be 17 more years — 2005 — before the Klan ringleader, Edgar Ray Killen, was finally tried and convicted and sentenced to 60 years for his role in the killings.

My conversation with Price came back to me when I saw a few weeks ago that Brenda Stevenson — a history professor at UCLA whose book on the 1991 killing of Latasha Harlins I admire — had been nominated by President Biden to serve on the new Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board. Last week, she and others nominated for the board testified at Senate confirmation hearings.

The operating principle behind the cold case board is that Price was wrong: We must not let bygones be bygones.

The history of racial violence in the United States is replete with cold cases. Anyone who has been to the immensely moving national lynching museum in Montgomery, Ala., knows that only a fraction of the violent crimes perpetrated against Black men and women in the last century were investigated and punished.

Many people are familiar with the Emmett Till case, which was reopened by the Justice Department in 2017 as part of its own cold case efforts, and then closed again last month with no further prosecutions. But there are countless others. To name just a random few, there’s the case of Rogers Hamilton, a Black 18-year-old abducted by two white men and then shot in the head in Alabama in 1957; James Brazier, a Georgia man who died after his skull was fractured by two white police officers in 1967; Clarence Triggs, a Black bricklayer shot by “night riders” in Bogalusa, La., in 1966 after being promoted into a job some believed should be for whites only.

Their killers were not punished. There have been efforts to reinvestigate their cases (and many others), but it is extremely difficult to bring new charges after decades have passed, evidence has disappeared or disintegrated, statutes of limitations have expired, and witnesses and perpetrators have died.

I don’t mean to suggest the newly appointed board will change that, or that it will necessarily result in new trials. The commission is limited in its mission, and in many ways is itself an acknowledgement that the era of criminal prosecutions is coming to an end for these cold cases from 1949 to 1979.

But even where there’s no prosecution, history still gets to render a judgment.

The new board’s modest goal is to make sure files and records of unsolved civil rights crimes are in the public domain, available at the National Archives for historians, journalists, researchers and others to study. Board members will hunt down documents and data, make decisions about which sealed or classified documents may be released and which may not, and work to make sure files are accessible, digitized, findable.

“Sometimes it just takes fresh eyes,” said former Sen. Doug Jones (D-Ala.) at Thursday’s hearing. “A successful prosecution is not always possible with these cases which are so old, but knowing the truth can bring healing and peace.”

Jones, who sponsored the legislation creating the board, successfully prosecuted two Klansmen for their role in the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, where four young Black girls died. The trial took place nearly 40 years after the crime.

For the record, I believe in forgiveness and mercy. I believe in statutes of limitations, and that time heals many wounds. But I don’t believe in burying the past. If we don’t want to repeat our ugliest history, we’d best not forget it.

“There were a few FBI agents who said, ‘I have no time to look at a 50-year-old case in which everybody involved is probably dead,’ ” said Cynthia Deitle, who spent two decades as an FBI agent working on civil rights cold cases, in an interview. “They said, ‘I’m not a historian — I’m an FBI agent.’ And I appreciate that. But the more persuasive argument is that it is our job to find the truth of what happened, no matter how much time has passed.”

And not because the perpetrators remain dangerous. Eighty-year-old Edgar Ray Killen, who used a wheelchair, was unlikely to reoffend by the time he was retried and convicted in the Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner killings.

But we have an obligation not to forget, to hold criminals accountable and to send a message to the world that bygones aren’t always bygones after all.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.