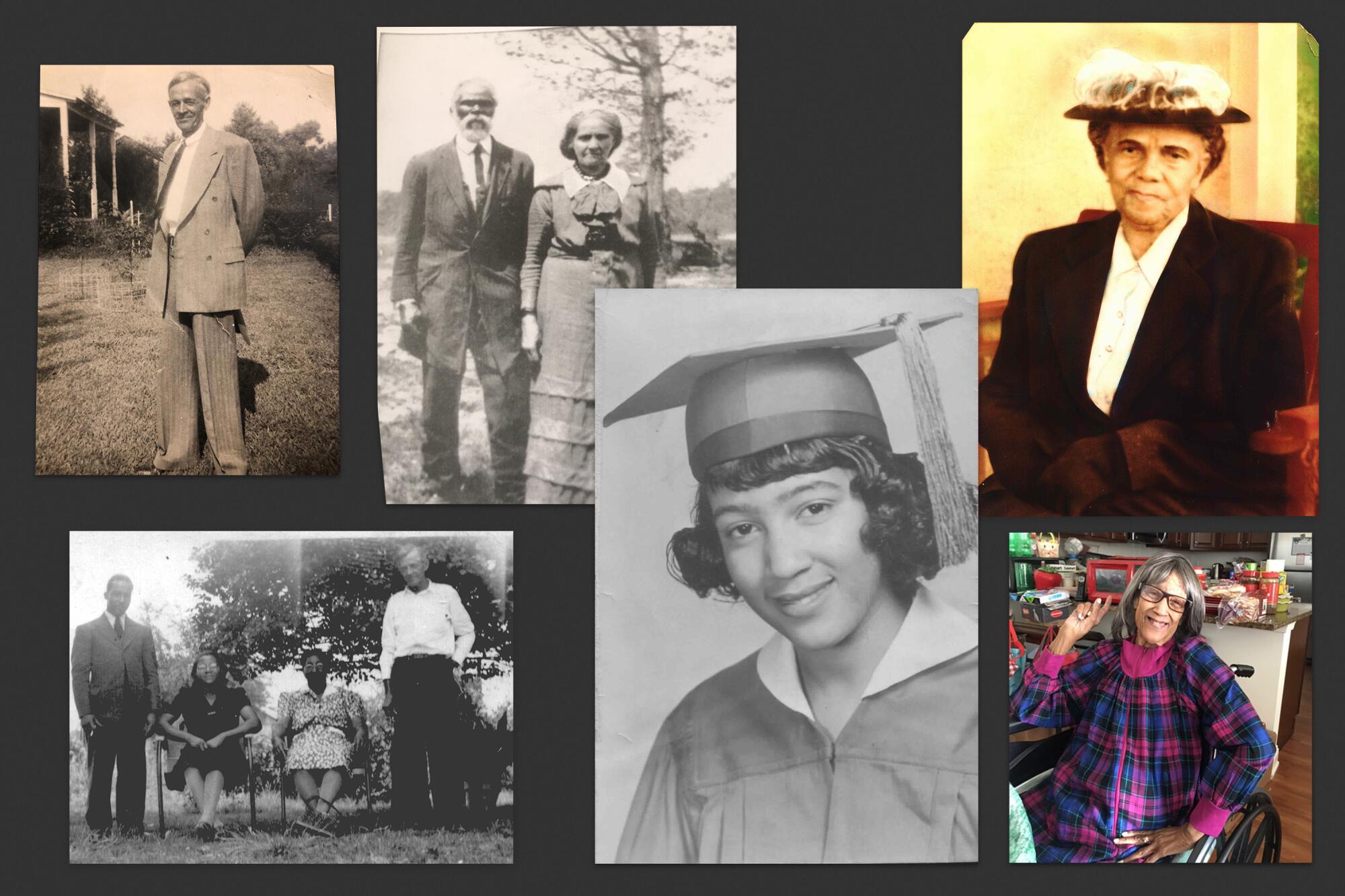

It all started with a picture on the wall in my family home in San Jose. I brushed off what seemed to be decades of dust to reveal a tall, white man smiling in a pinstripe suit. On the back of the photo was faded but beautiful handwriting:

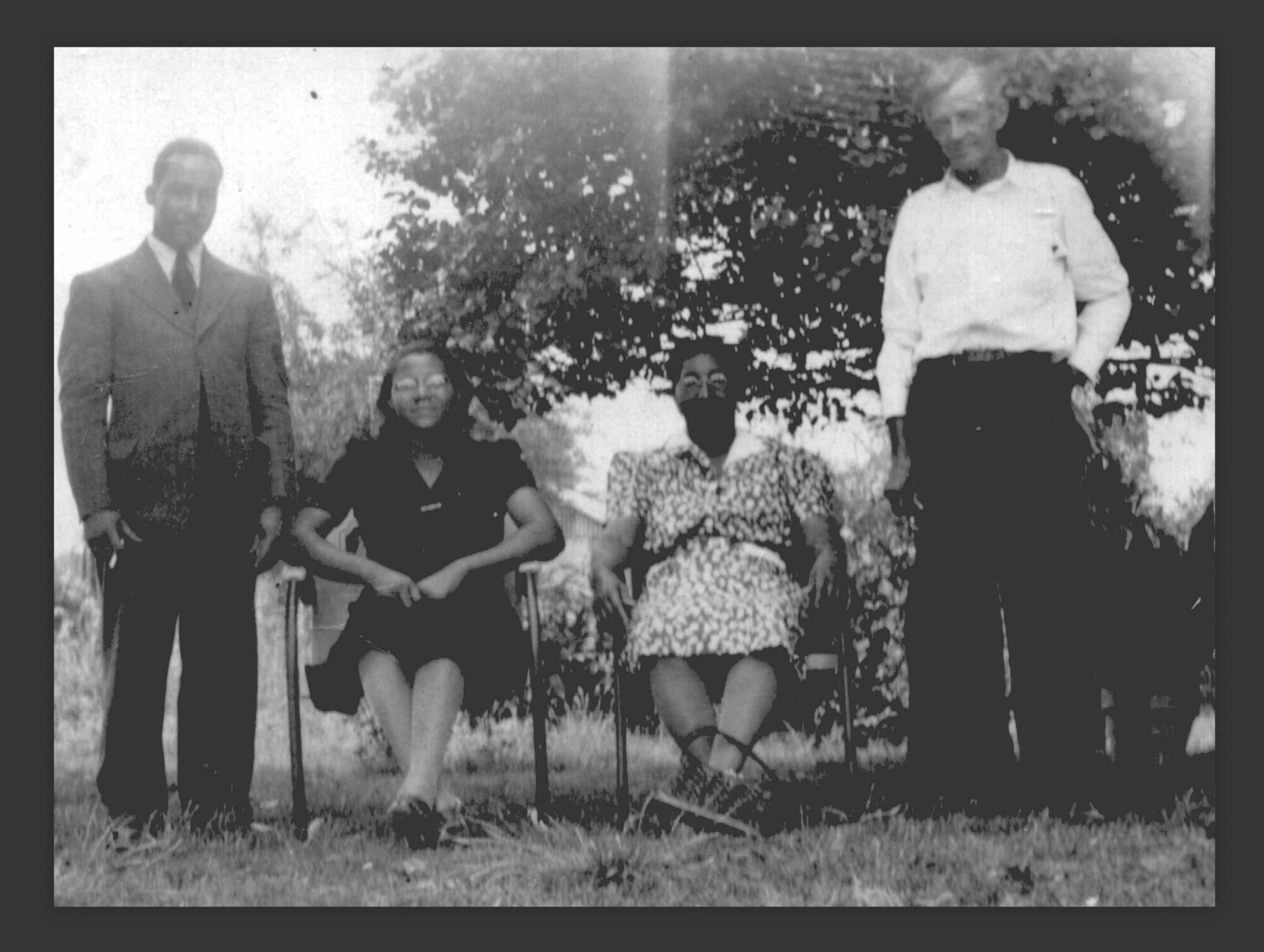

“This picture was taken around 1953, at 404 Winston Street. The same land that was owned by Uncle Tom, that he gave to Alma and Andrew Hocker as a wedding gift in the 1930s, during the Great Depression Era ... Uncle Tom had blond hair and blue eyes. He helped to restore some of the historic buildings in colonial Williamsburg, Virginia and Jamestown, Virginia. Love, Annette 4/16/80.”

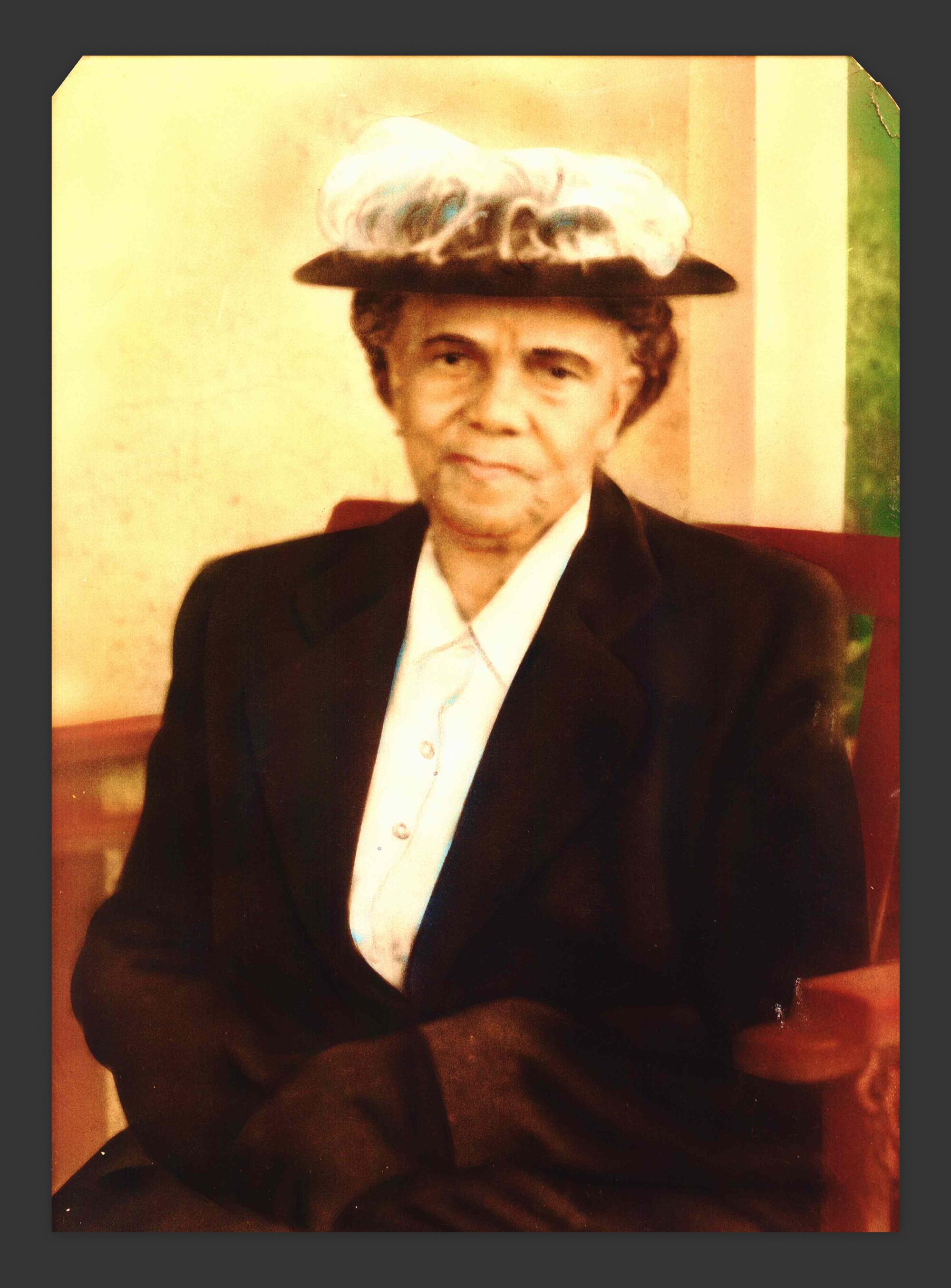

A lot about this piqued my interest, and so one day in October 2017 my dad and I called his sister Annette, whom I had not seen since I was a baby three decades earlier. She sounded so happy to hear from us. Annette, who was 82, told us that she had Stage 4 colon cancer and was in hospice care at her home in Willingboro, N.J. “But I’m hanging in there. I’m a tough cookie,” she quipped. “I am doing what we all got to do one day.”

Her voice came to life when I mentioned Uncle Tom’s name. The stories about her Uncle Tom — John Thomas Lewis — and others came tumbling out — for a year. We had countless phone calls in which Annette told me stories that she had heard from her own grandmother, and she recorded many details in meticulous handwritten notes. She passed along other records and documents, along with carefully labeled sepia family photos. By October 2018, we had recorded all the family stories. And then, a month after completing our project, Annette died in her sleep.

Annette knew she was passing along more than information and images. She gave me a sense of purpose, the same passion that had driven her and generations before her to amass this treasure and share it. As it is in every generation, it’s up to young people today to preserve what our ancestors and elders gathered.

This is the story that Annette told me about our family.

The story of Uncle Tom and our family begins with Jermame, the young girl who crossed the Middle Passage of the Atlantic Ocean in chains as a slave on a slave boat after being captured in Africa. She was 12 years old.

Jermame was the name the white people gave to her. Like Aunt Jemima. She had several children that were taken or sold. I know she had a Mary, an Amanda and a Martha. And there was another one, because there were four girls. They may have had different fathers, because enslavers would just mate you or breed you like you were cattle.

Jermame mothered Amanda and other children sold into slavery. Amanda mothered Ida. Both were slaves of a white judge in Richmond, Circuit Court Judge John Meredith. He impregnated your great-great-great-grandmother Amanda Davis. The child was Ida.

Ida looked like a white woman. She had blond hair and blue eyes. The judge really loved her as his child. When the judge would go out on his circuit runs, he would always bring a gift back home. Most times, it was something like a necklace and earrings. But he would give maybe the necklace to his daughter Ida and give his wife the earrings, or vice versa. And the wife became very jealous of Ida.

As a young teenager, Ida was put on the slave block when the judge was on a circuit run. The judge was heartbroken to learn that Ida had been sold. Judge Meredith freed her mother, Amanda, to go live with her and look after Ida because he was worried about her.

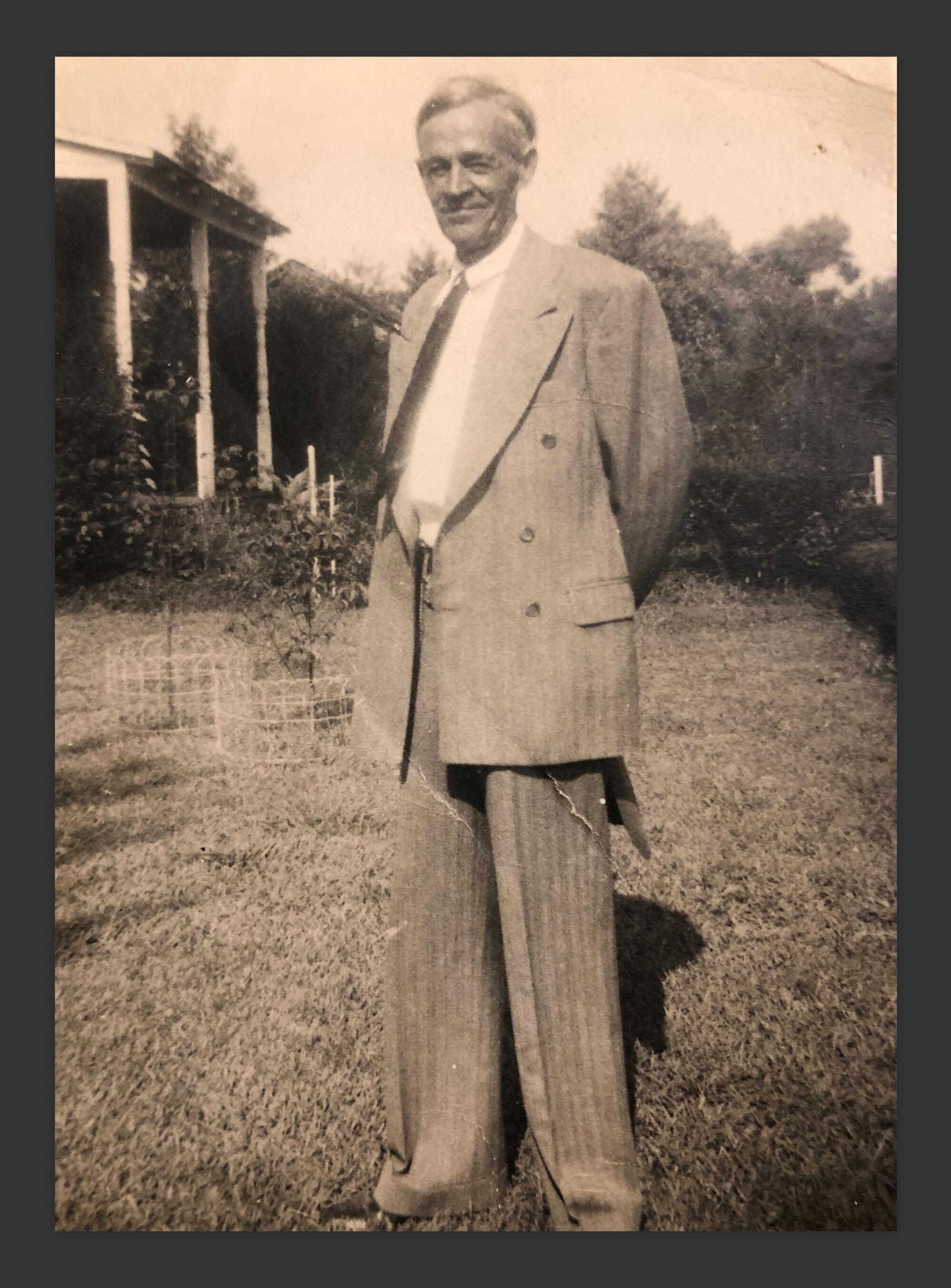

Ida was sold to a Native American blacksmith, Charles Lewis. Ida did not want to go with him. Charles, being quite strong and muscular, just slung a kicking and yelling Ida over his shoulder and took her to her new home in Buckingham County, Virginia.

This was just before the Civil War was fought. After the Civil War, Charles married Ida. Before the war, Blacks were not allowed to marry. They had a ceremony that they called jumping the broom.

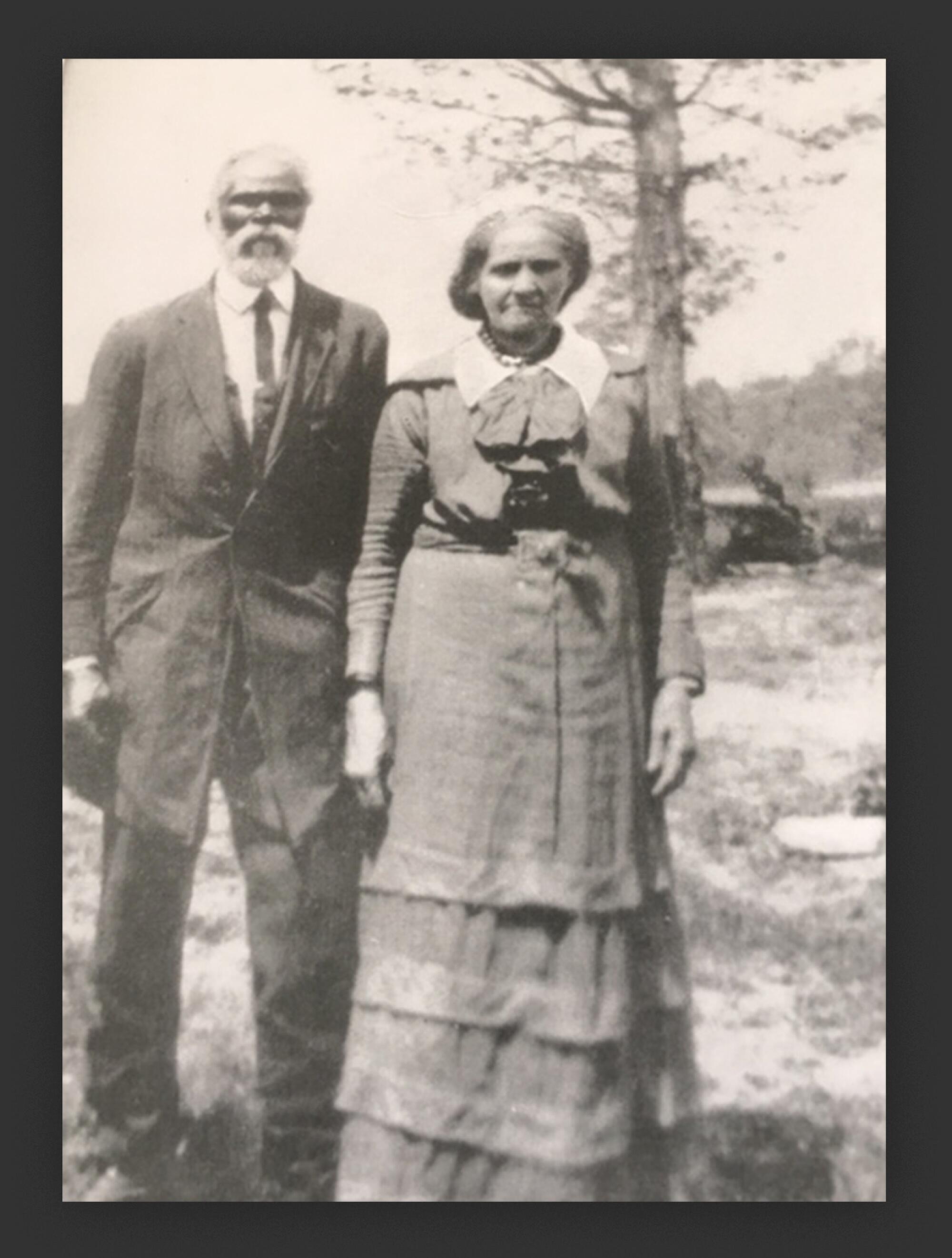

Ida and Charles went on to have several children together. One of them was my grandmother Rebecca. Rebecca adored her father and would tag behind him as a child. Her father showed her the different plants in the forest. I remember as a child tagging behind Rebecca looking for a certain plant that she used to make cough syrup.

Amanda was a midwife and delivered babies. Ida became a midwife and she showed Rebecca what to do. And Rebecca was a midwife.

Rebecca was a brave, independent, hard-working woman. She delivered 600 to 700 babies. She delivered your father. She delivered me.

Her Sunday prayers started before daybreak and went to 7 or 8 a.m. If I would stir and wake up, my mother, Alma, would softly say for me to go back to sleep, which I pretended to do. But I was listening to every word being said in Rebecca’s prayer.

One thing that stood out in my mind all my life was how Rebecca would end all of her prayers. She always asked God to bless her children’s children. As a child, it made me feel so safe that God was blessing me because Grandma had told God to bless the children of her children.

One of the times Charles was away, there was this drunken Caucasian man that came through and saw your great-great-grandmother Ida. He overpowered her and raped her, and she became pregnant with his child. This was Tom.

Tom’s older sisters and brothers knew he was a product of rape and for the most part ostracized him because he looked white. But my grandmother Rebecca was nice to him because that was her mother’s child.

When he came to Richmond, Tom got jobs, and they treated him like a white man. Nobody asked him if he was Black because he just looked so white. And he really got good jobs and was able to get good money compared to the Blacks in that era.

He married a dark-skinned woman, Bessie. I can see her now. If he got on the public transportation with his dark wife he would always end up with a police problem because they tried to make him move and stay in the front and make her move to the back. They would think he was drunk or something.

It just got to the point that he had to buy a car. So Uncle Tom was the first person to buy a car where we lived in the Providence Park neighborhood of Richmond.

Once Bessie packed him up a nice lunch and brought it down to him on a construction site. Tom’s white co-workers joked, “Oh, you got your maid bringing you food!” Tom said: “That’s not my maid. That’s my wife!”

Tom had a very unhappy life in a sense because he did not fit in either world. He was raised in a Black world, but he had the white look. He associated with Blacks. But to get in a public situation it always created a problem.

Uncle Tom was a generous man. He was key in giving our ancestors a leg up during the Great Depression. He never had kids of his own, so he treated Rebecca’s children as though they were his.

He was prosperous because he owned a lot of property. He bought up a lot of land. Uncle Tom was the one who gave our parents Andrew and Alma Hocker the land where they built the house at 404 Winston Street in Richmond.

I had a lot of admiration and love for Uncle Tom. He was a World War I veteran and fought over in Germany. As a child, I would just love that beautiful hair of his because all of the doll babies that they made for Black people had blond hair and blue eyes. I would get the comb and try to comb his hair. I would say, “Uncle Tom, please let me comb your hair!” And he would say, “Bah! Get away! Get away!”

But he was a sweet person. And his wife, Bessie, she was a saint. She never had a bad word to say about anybody. Aunt Bessie died at 51, many years before Uncle Tom did. He loved her. That was a love story. He didn’t have any wife or anybody else after her. In January 1968, Uncle Tom passed away.

Tom worked hard and cared for our family, just like his sister Rebecca, my grandmother. She taught me the stories of the women who came before her: Jermame, Amanda and Ida. She taught me to respect the courage and strength that made our lives possible. Thank God for that young, brave and strong African girl whose blood flows through the bodies of her great-grandchild’s children’s children today.

The incredible history my Aunt Annette shared with me in the final year of her life was almost lost. Because of one intriguing photo on the wall at my family home, I called my aunt. Because of one phone call, I ended up acquiring two centuries of family history. And knowing that story, I can only marvel at the lives built by Jermame’s descendants.

Annette told me that they include doctors, teachers, preachers, scientists, an opera singer, a blues guitarist, authors, actors, a film director, a judge, world travelers, a Realtor and managers. They have attended Princeton, Yale, Harvard, Caltech, the University of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University, Trenton State, Rowan University, Howard University, Virginia Union University, the University of Pittsburgh, Virginia State University, the University of Miami, Florida State University, Boston University, Georgetown University, Stanford, the Medical College of Virginia, Dartmouth and Cambridge.

So thank God for Jermame, and thank God for her heirs like Annette who kept our story alive.

Zachary Hocker is an aspiring author in San Jose.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.