When one grows up Native and faulted for not being ‘Native enough’

Book Review

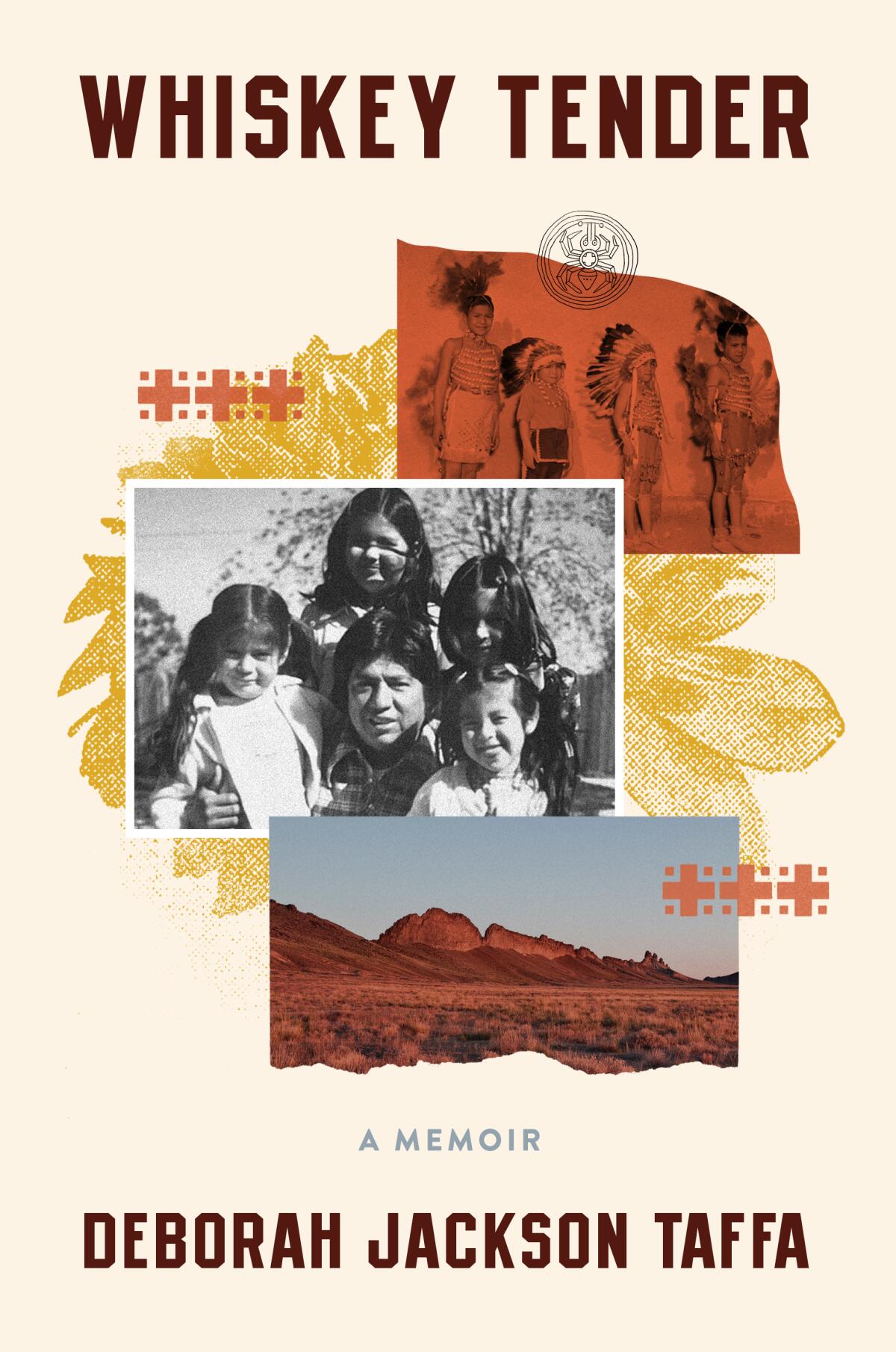

Whiskey Tender: A Memoir

By Deborah Jackson Taffa

Harper: 304 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In the first chapter of her debut memoir, “Whiskey Tender,” Deborah Jackson Taffa declares that the story she’s about to tell is “common as dirt.” This isn’t an insult or a minimization — quite the opposite. In a culture that reveres the land and all that springs from it, that nourishes and is nourished by it, the earth is sacred.

Taffa does mean, however, that she doesn’t believe her story to be unusual because thousands “of Native Americans in California, Arizona, and New Mexico could tell it.” This understanding came to her much later in life, after traveling and learning that a quarter of the world is Indigenous. In her childhood and adolescence, she often felt isolated as an Indigenous person, and the book follows her growing understanding of her identities and cultures and the way she was imbued with shame that was not hers to carry.

Born to a Quechan (Yuma) and Laguna Pueblo father and a Catholic Latina mother who never discussed being descended from both Spanish conquistadors and Native people, Taffa was raised straddling ways of viewing and approaching the world.

“Despondency hung over the [Yuma] reservation, and when toddlers and children acted rebellious, adults saw hope and verve. A sassy girl was a girl who might make it,” she writes. Like many other parents, hers changed their tune about her rebelliousness when she was a teenager. But having pluck and curiosity encouraged in childhood meant that she was able to recognize that things were more complicated for her family than they were willing to admit.

Her parents’ attitudes about things diverged drastically, as did their temperaments. Her father seemed to be raw to the world, his memories and traumas always just beneath the surface of his skin, spilling out in stories and outbursts alike; her mother anchored herself with prayer, preferring to keep her hurts private, her doubts buried, her insecurities hidden away behind a competent and confident facade. They were united, however, in their commitment to the family they’d built and raised together.

Taffa’s memoir is chronological, beginning when she’s 3 and ending when she’s 18. It follows her family’s life in Yuma, Ariz., and their later move to Farmington, N.M., for her father’s work. Throughout, she weaves in historical context of Native history, describing the atrocities the U.S. government inflicted against Native America, as well as the various tactics Indigenous people have long used to fight back. But she doesn’t shy away from complexities; in one chapter, for example, she explores reasons her family members enlisted in the military during World War II: “Their generation had something to prove, and across America, Natives stood in line at draft offices ready to fight against the totalitarian idea of a super race, even though they would serve for a country that treated them as ‘lesser’ at home.”

Over the years, Taffa experiences racism from white people and also criticism for not being “Native enough.” She watches her mother attempt proximity to whiteness and encourage it in her children. She sees the ways her father and his brothers live with traumas they have difficulty speaking about directly and how some turn to alcohol to numb their pain.

As Taffa approaches adulthood, her own anger at the injustices her people have suffered grows inside her. She becomes depressed, loses her ability to focus on school the way she used to, and begins drinking and staying out late with her peers as well as sneaking out of the house to get high and hike in the early mornings. She stops believing in her parents’ insistence that formal education will bring her the freedoms and life she wants to pursue.

Crucially for a memoirist, Taffa both allows her adult perspective to color her approach to her memories and resists explaining away her youthful rage or negating its validity. There was plenty to be mad about then; there is plenty to be mad about still.

But Taffa does begin to realize that change is not only inevitable, but sacred in and of itself. Her Quechan ancestors’ traditions eschewed materiality, as exemplified in their funeral rituals, which involve burning the deceased person’s belongings and once extended to burning that person’s home. Taffa’s Aunt Vi tells her a story about a ceremony that was abandoned in the 1950s because one of the families participating in it had lost three of its members in one year, leaving no one alive in that family who knew how to perform the ritual. “The world was perpetually in flux,” Taffa writes, “too sacred to tether, and the elders said this change was part of the world’s ongoing ceremony. Aunt Vi said it was a reminder that even ceremony was material. There was only true power and endurance in nature.”

Now the director of the MFA in Creative Writing Program at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, Taffa has clearly come a long way in her ability to accept change and synthesize the various elements of her identity. At the end of her memoir, she gives a brief overview of how this happened — working at Yellowstone National Park, traveling to Hog Island, then Alaska, Indonesia and several countries in West Africa — and I wished she would elaborate on what she learned. I can only hope that this might be the project of a future book, which I can only assume will be as rich and wise as “Whiskey Tender.”

Ilana Masad is a books and culture critic and author of “All My Mother’s Lovers.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.