Editorial: There’s no going back on sentencing and prison reform

The novel coronavirus seeped easily into jails and prisons. It entered along with newly arrived prisoners, and with the officers and others employed in those facilities. When the people locked inside paid their bail or completed their sentences, and when the work shifts ended, the virus went home along with the formerly incarcerated and the employees, and spread to their families, friends and neighbors.

Jails and prisons are ideal disease incubators because they are locked, crowded and often in poor repair, with spotty sanitation and less than stellar health services. That’s a particular problem in California, with its 35 adult state prisons and correctional medical, training and rehabilitation facilities; its four state youth correctional facilities; its 12 federal penitentiaries, correctional institutions, prison camps and detention centers; its 116 county jails; its 21 juvenile halls and probation camps; its eight U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers; its five state hospitals (which house, among others, people locked up while receiving psychiatric treatment so they can then stand trial); and its numerous city jails, police jails, inmate reception centers and temporary holding cells.

California has been through multiple reimaginings of its criminal justice system, and together those political and philosophical shifts have built the complex of lockups that pepper the state and have through the years housed millions of prisoners (the notorious population peak of 173,000 in 2006 included only adult state prisoners, not all those accused or convicted people in county, federal and other institutions). In the final quarter of the 20th century, this state was the nation’s criminal justice thought leader, and the thought was overwhelmingly this: Lock up more people, for less cause, and for longer.

Staggering under the weight of the now-exploded jail and prison population, California more recently has led in the opposite direction, focusing on shrinking the incarceration footprint and treating more people for the underlying health or social conditions (psychiatric problems, substance use, trauma, poverty) that put them on the path to criminality, rather than for the crimes themselves, at least in those cases in which the crimes were less serious. After all, there is something particularly daft about putting punishment, which satisfies an emotional demand in those of us with few serious troubles in life, ahead of treatment, which addresses the needs of those with severe health, psychiatric, emotional and financial burdens to bear.

The change began almost exactly a decade ago, mostly because it was forced by a federal court that found California’s prisons to be actually criminogenic — more likely to turn people toward crime instead of away from it — and that in any event the overcrowding and lack of sufficient medical and mental health services violated the 8th Amendment guarantee against cruel and unusual punishment. Change began in earnest with “realignment,” a policy and legal framework that sent people to county jail who otherwise would have gone to state prison. But really, all that meant was a difference in which set of bars a person sat behind.

There were also winning ballot measures to blunt the most onerous aspects of the “three strikes” law, to turn drug possession felonies into misdemeanors, and to give more people in prison incentives to participate in rehabilitation programs. The state has begun to reestablish those programs in the last 10 years, now that prison classrooms and clinic space formerly filled with triple bunks have been emptied to serve their original purposes, and resources formerly used to manage people struggling with the psychic injuries caused by severe overcrowding can again be used to hire teachers and other experts.

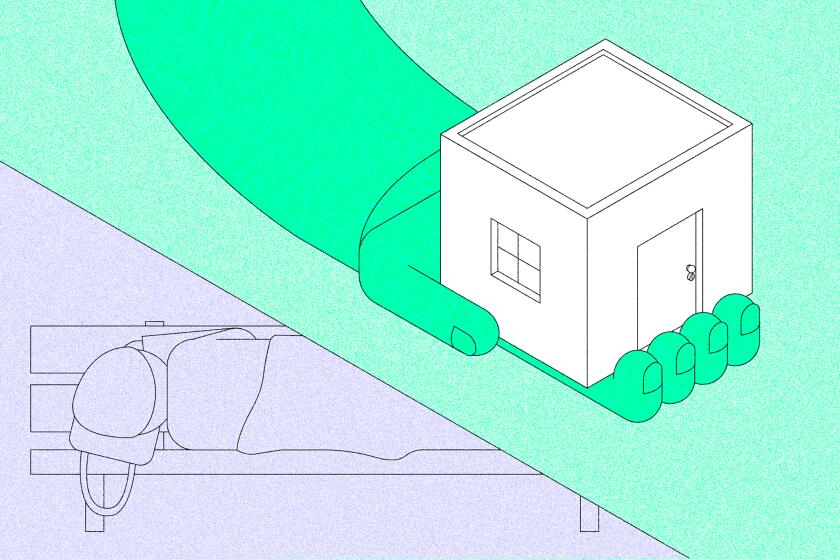

But the new era of California criminal justice that these changes signaled — the one in which the state’s prison gulag locks up hundreds of people instead of hundreds of thousands, and resources are spent on healing the wounds of crime victims and survivors instead of on decades-long prison terms, and people who leave prison are given the tools to make a fresh start at living productive, responsible lives instead of carrying, by virtue of their felony records, everlasting punishment that prevents them from going to college, earning a living, even coaching their child’s soccer team or serving as an officer of their homeowners association — that new era never quite came into focus.

Until COVID.

The virus changed everything. Because it spread so quickly behind jail and prison walls but could not be contained there, state and county justice officials took extraordinary steps to reduce the number of people locked up. The Judicial Council (the leaders of the state’s judicial branch) essentially swept aside all the county court bail “schedules” that assign monetary amounts for people accused of various crimes, and set most of them to zero. In other words, for all practical purposes they temporarily ended bail. District attorneys and police union leaders expressed a great deal of consternation, and there were a few reported cases of car thieves arrested, booked, released and arrested again on the same day. But for the most part, the program worked with no negative impact on public safety, and it forced policymakers to ask: Why have we been locking up people for days, weeks, months, just because they don’t have the money to pay their bail?

State prisons quickly released medically vulnerable prisoners, prompting the question: Why were we keeping them locked up in the first place, if they posed no risk to the outside world? Wardens released prisoners with less than a year to run on their sentences, forcing state officials to ask: What was the point of keeping them inside? And what about the elderly prison residents, who may well have committed horrid crimes 20, 30, even 40 years earlier, but were now well into their 70s and 80s and a risk to no one? Did these people really need to stay in prison, with or without a deadly pandemic?

Meanwhile, Los Angeles County was moving ahead with a program of Alternatives to Incarceration — a health-based set of principles meant to create a decentralized network of services for people with challenges and conditions that, left untreated, could send them careening toward a criminal justice system that tends to grab people and compound their problems to such a degree that they can never truly get out. The Board of Supervisors adopted the program, called Care First, Jails Last, as one of its final actions before California virtually closed down for COVID-19.

Now the state is on the verge of reopening and getting back to normal. But what should normal be? There has been a disturbing jump in violent crime, although it does not appear to have anything to do with zero bail (ended by the Judicial Council but kept in place, in one form or another, by some Superior Courts), or with release of elderly or medically vulnerable prisoners. It may well have more to do with a still-unbuilt system of care and an overbuilt system of punishment that keeps much of the nation’s population disconnected, dispossessed, frightened and angry. We’ve seen precipitous jumps in crime before, and we responded then with more police and more prisons. A generation was lost. But for the current generation of Californians we have a shot at a do-over — a care system based on health, protecting people not just from COVID-19 but from all manner of ills that put them on a downward spiral of failure.

We will still need prisons, and we will still include punishment as part of the mix of responses to crimes that inflict serious damage on people and communities — but in measured, appropriate doses, enough to keep people safe, yet not so excessive as to forever condemn the perpetrators who can make amends and be brought back into the fold.

The other path is to reopen, or keep open, the complex of prisons in which tens of thousands of people can nurse their hopelessness and remain vulnerable to pandemics. Even with the reduced prison population, California has more than 50,000 prisoners who have tested positive for the coronavirus and hundreds who have died from it. But we’ve walked that path. It’s time to turn around and try a different one.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.