Op-Ed: How John Coltrane has sustained me during the pandemic

Lately I’ve been thinking about art that is sacred, but not religious. Art that sustains us in hard times, but doesn’t tell us what to think. Years ago, in Houston’s Rothko Chapel, I had my first experience with that kind of art. Giant, dark, undulating with the natural light of that nondenominational space, Rothko’s paintings served as a connection point for me during a difficult time.

“Difficult time” has now been redefined.

We are over a year into a global pandemic that became real for America last March. For some more than others, but in a broader sense for all Americans, there is nothing left that the coronavirus hasn’t touched. More than anything, when I think back to last March, I remember this persistent longing to tell my young kids, It’s OK. I’ve been through this before. It’s OK. But like every other parent in America, I couldn’t.

Last March, terror was a bright ribbon that ran through everything. So little was known about COVID-19 other than that record amounts of people — particularly our most vulnerable populations — were dying. Like the infection curve itself, the tragedies of the past year established an early and horrific baseline that seemingly doubled each day, spiking at certain points.

In my own life those tragedies arrived in every shape and form. There was the day our library closed — no new books for the kids during lockdown. There was the day we told my parents they could no longer see their grandchildren. Later in the year, there was the first day we knew someone who died of COVID-19, a neighbor. Then the hardest day, in November, when my father-in-law, a man we loved, admired and enjoyed in equal measure, slipped from a ladder, fractured his spine and died. That was the day we wondered if my husband should go see him in the hospital to say goodbye. Was it worth the risk?

He went. A week later we stood at the small funeral. I sang “Amazing Grace” through my mask. We could not hug anyone — perhaps that has been the most distressing part of all. In a year of unbearable loss, we cannot do the one physical act we need in such moments. We cannot hold each other up. Maybe that’s why now I am sad and tired and losing hope, oddly, when there are finally reasons to hope.

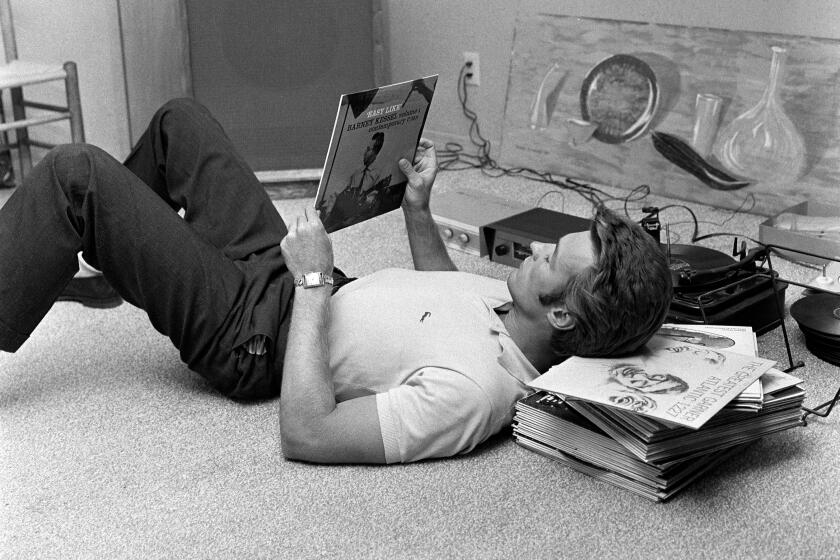

This is where John Coltrane comes in. Specifically, “A Love Supreme.” An album with an uncanny, multiyear history that begins with Coltrane being fired by Miles Davis(!), it includes a quest for sobriety, self-inflicted isolation, intense prayer and Coltrane’s demand for artistic control. I’ve probably listened to it 50 times during the pandemic. I return to “A Love Supreme” the same way I returned to Rothko’s paintings years ago, for one simple reason: it holds me up.

I’m far from the first person to call Coltrane’s work sacred. Some professional jazz musicians refuse to play “A Love Supreme” because it is “too personal to Coltrane.” Coltrane himself only performed it live once. But there is an entire church in San Francisco of people who, at least before the pandemic, regularly gathered to listen to “A Love Supreme.” After the year we’ve had, that makes sense to me.

How to keep Coronavirus stress at bay: Listen, really listen, to your favorite albums, front to back, without distraction.

“A Love Supreme” was recorded in December 1964, after a summer of rippling unrest across the United States, when many Black communities reached their breaking point with predominantly white police forces. It was recorded a little over one year after President Kennedy was shot, and right as President Johnson was escalating our involvement in Vietnam, a war that would eventually, by some estimates, claim more than 3 million lives. That, too, was a difficult time.

But it was also a time of hope: the Civil Rights Act had just been signed into law. And in Dix Hills on Long Island, Coltrane welcomed his newborn son. He was sober. He went into a room for five days and emerged with an outline of what would become a 33-minute masterpiece that still serves as a sacred connection point for people all over the world.

“A Love Supreme” is the exact opposite of the jazz you put on to make dinner guests feel welcome. It demands your full attention and in doing so pulls its listeners into the present moment. Be here, now, it says, even though the only actual words of the album come from Coltrane himself. More said than sung, at one point, he repeats the album’s title like a mantra.

The other day, demonstrating just how often I’ve leaned on that album in the last year, my 4-year-old son repeated Coltrane’s words. He was playing dino-ambulance, his new favorite game, and as he drove an ankylosaurus down the hall, sirens whirring on his toy truck, he said it low and clear: “A love supreme. A love supreme. A love supreme.”

I used to believe that the best art connects us to each other. I still think that’s true. But now when I say “other” I don’t just mean person to person. In a rare interview recorded shortly before he died, Coltrane told the interviewer, “The truth itself doesn’t have any name on it to me.” So call it God, call it physics, call it enlightenment. This pandemic year I’m calling it “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance” and “Psalms,” the four parts of the only thing that’s pulling us through this difficult time: a love supreme.

Natalie Ruth Joynton is the author of the memoir “Welcome to Replica Dodge.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.