Editorial: A year of COVID-19 has left immeasurable holes in American life

The statistical measures of the COVID-19 pandemic, which a year ago forced a stunning global shutdown of schools, businesses and travel, can be hard to contextualize. We’ve swept past 2,600,000 dead worldwide, with a fifth of them — more than 525,000 — in the U.S., and more than 54,000 of those here in California. The human impact is staggering and still growing — 117 million cases globally, nearly 30 million in the U.S. — and the full effects won’t be known until this crisis is safely behind us.

Just 13 months ago, the pernicious disease didn’t have a name, and even now no one can say with absolute certainty how long this coronavirus has been around or how it infected its first human. Most sobering: As disastrous as this is for humankind, at a fundamental level it is nature doing its thing, which reinforces the reality that as smart as we might think we are, nature doesn’t care.

The losses are both individual and mass: Futures canceled for those who died and curtailed for those who survived. Families left to mourn and struggle to fill the emptiness. Neighborhoods and communities — particularly those comprising low-income people of color, where the virus has been most destructive — straining for normalcy.

The majority of the dead were over age 65, and many were living in nursing homes or other ostensibly supportive environments. So the virus stole the lives of elders — parents and grandparents — and left younger generations to grapple with grief, loss and, in some cases, guilt.

What if I had quit work and not brought the virus home to my family? What if I had cared for my parents myself and not persuaded them to move into assisted living? What if urging them to forgo independence for the sake of safety brought them to an early death?

The resonant truth of the coronavirus crisis is that none are safe and all are affected, even if only by nagging doubts and dark uncertainties.

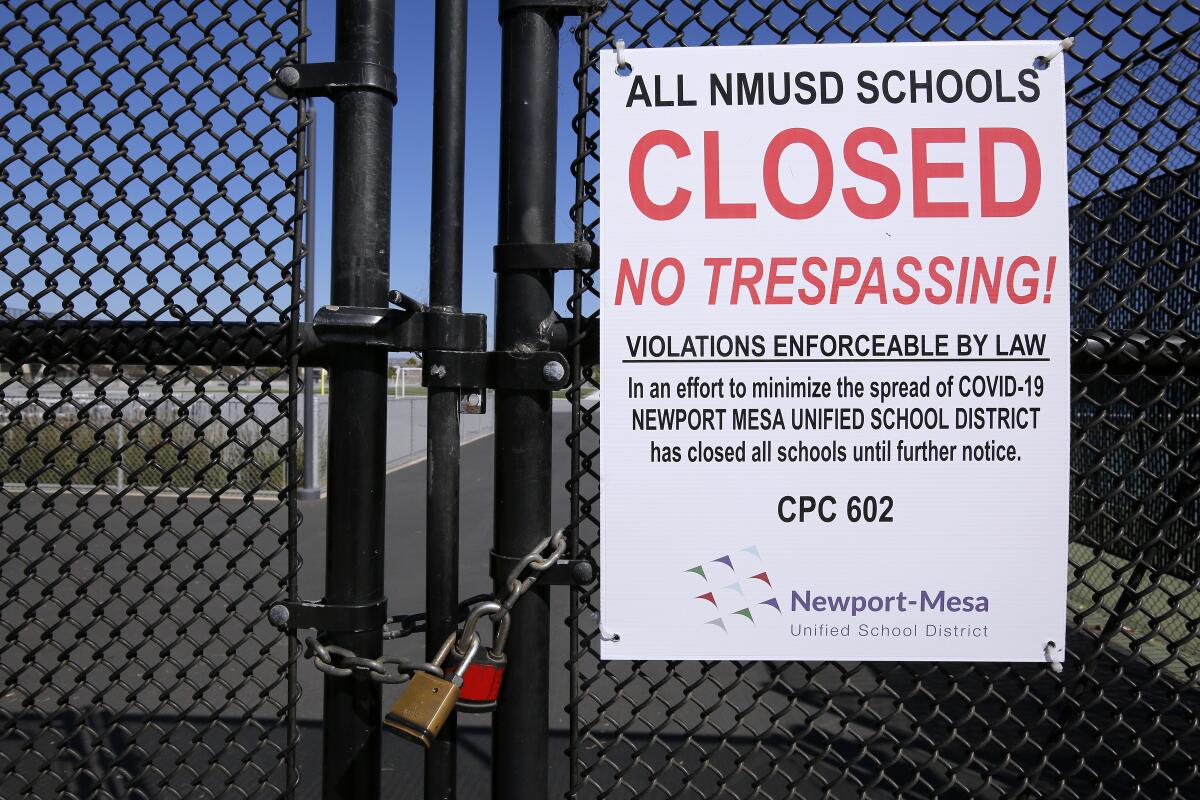

The World Health Organization announced the coronavirus outbreak had become a pandemic on March 11, 2020. Since then, the virus has seemingly touched all aspects of life in Southern California and beyond. The Times looks back on a full year of life in a pandemic.

Young children, too, must wrestle with the deaths of parents and grandparents — role models they otherwise would rely on to guide them through these terrifying times. Communities must grapple with members taken from them prematurely, with potential unfulfilled. It’s not a lost generation but a random collection of holes ripped in the multi-generational fabrics that bind families, neighborhoods, communities. We’ll never be able to envision what kind of quilt those missing fragments might make if we stitched them together.

We fix on milestones, as though the 500,000th death somehow means more than the 499,999th. In reality, because health officials were so late to understand the sweep of this infection, we can’t even rely on the numbers. So these astoundingly high death counts are just floors, really, the minimum measure of what we know, not of what has occurred.

But one thing is certain: The count continues, as does the economic pain that has befallen people untouched by the virus itself, with careers and entire industries upended.

There is a lot to be angry about. President Trump’s callous dismissiveness about the pandemic, even after he too was hospitalized with COVID-19. State governors who pooh-poohed the reality and resisted the guidelines and restrictions that would have saved lives. And those delusional deniers who continue to claim that science is a leftist conspiracy to subvert personal freedoms, oblivious to the dangers they pose to the rest of us in their pugnacious embrace of an uncompromising individualism. It’s not “America first” so much as “me first,” putting the lie to the aspirational notion that when the chips are down, Americans hang together.

Immigration helped make Asians the fastest-growing minority group in America. But the volatility of the issue has fueled a rise in xenophobia and hate.

Yet most of us do hang together, do support each other, do recognize the broader necessity of working for the common good. Imagine how much worse this crisis would have been were it not for emergency workers, hospital medical teams and support staffs who have been struggling with their own losses, personal grief and the nagging fear that their jobs might endanger their own families — they do the work anyway. Or the essential employees who’ve continued to provide us with food, mail, water, power and other necessities, despite the risks.

So here we are, a year after government officials began ordering businesses and schools shuttered, after we began looking at each other warily and worrying over a tickle in the throat, and after we began sheltering in place against a danger we could not see. It is, in the end, a reminder that for all of our human advances and hubristic successes over nature, we are still a part of the web of life and susceptible to its capricious ways.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.