Editorial: Time for L.A. County to go its own way on bail

The recent defeat of Proposition 25 leaves California’s powerful bail bond industry intact, with money bail in place and with opponents of that absurd and discriminatory system sharply divided over what to do next. Reformers disagree over whether it is politically feasible or even legally possible for state lawmakers to write a new bill to do away with bail, whether bail will inevitably disappear anyway because of court rulings and alternative pretrial release programs, or whether it is now more entrenched than ever.

The reformers can at least agree that money bail undermines basic American principles of justice and should be eliminated in California as soon as possible. Any system that relies on suspects’ wealth or poverty to determine whether they’ll be locked up or sent home before trial is an abomination in a nation that professes equal justice under the law.

At issue is a basic question: How do we justly treat people between the time they are arrested and accused of a crime and the time they finally present their defense to a jury (or enter into a plea bargain, or have charges against them dropped)?

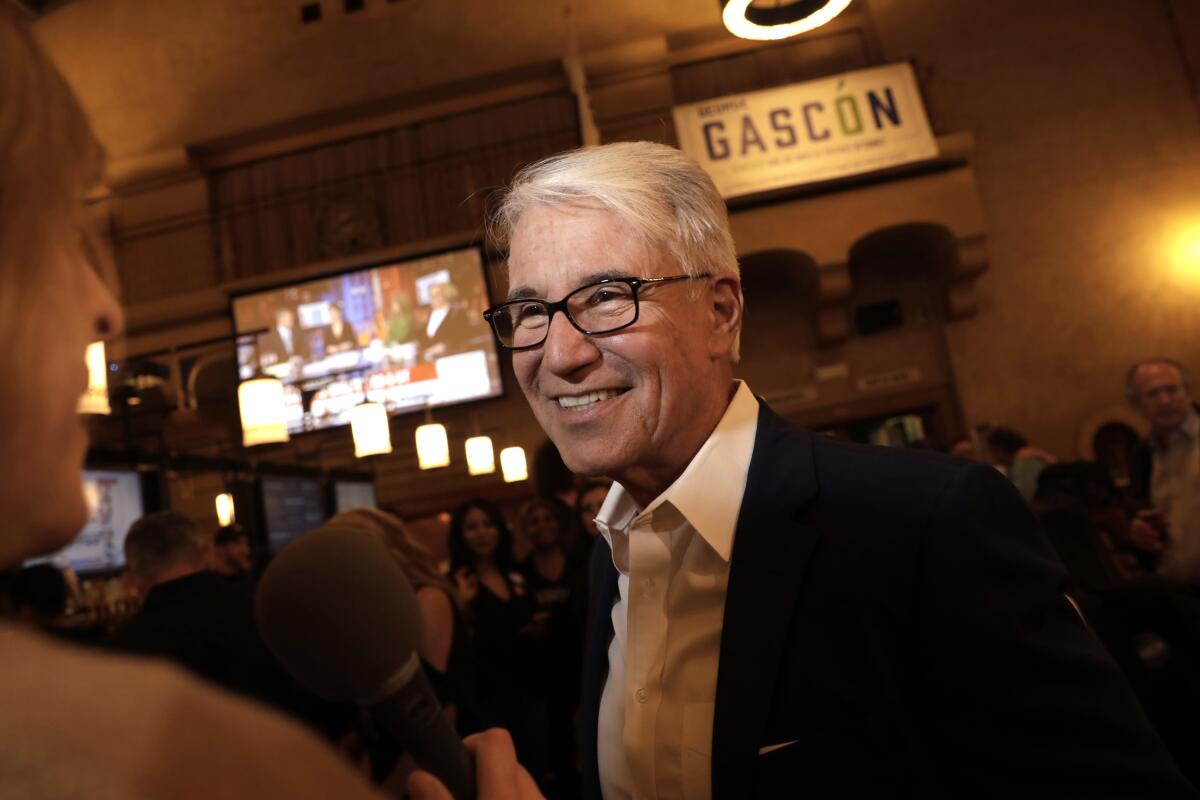

With statewide efforts having been stymied for now at the ballot box, it is more important than ever for Los Angeles County to take its own path. It is the nation’s most populous county, with more than 10 million people, and has the largest local criminal prosecutorial and court system. It has also embraced a more aggressively reformist path by electing George Gascón as district attorney and by adopting Measure J, which directs funding to alternatives to incarceration rather than jail. It’s well past time for the county to move more decisively to eliminate money bail and replace it with a program of pretrial services to ensure that defendants show up for court hearings and stay out of serious trouble before trial.

Up to this point, the county’s progress on this issue has been slow. The Board of Supervisors called for a study of alternatives to bail in 2017 and set a timeline for pilot programs a year later, but the sense of urgency dissipated when state lawmakers passed a bill to eliminate bail (it was that measure, SB 10, that was suspended and ultimately overturned by the defeat of Proposition 25). Note to the supervisors: A recommitment to swift and decisive bail reform is in order.

The county has also been stymied by a disagreement among reformers over the proper role of risk assessment tools — algorithms that can help probation departments, prosecutors and judges determine how likely a defendant is to flee or cause harm before trial. Note to justice activists: Meaningful pretrial reform requires public support, which in turn requires confidence that broader pretrial releases won’t endanger public safety. We need some kind of criteria to at least help prosecutors decide whether to seek pretrial detention.

Surprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic may have helped the cause of reform more than hurt it. The Los Angeles County Superior Court adopted a series of emergency orders that waive bail for some crimes in order to reduce the jail population and control the spread of infection. These orders remain in place, even after a parallel state order was revoked. L.A. has seen crime increases during the year, raising public concerns about pre-trial release, but criminal justice leaders do not attribute the increases to the reduced jail population.

At the same time, the court has expanded its agreement with the Bail Project, a nonprofit organization that puts up money to spring defendants who can’t pay bail on their own. Los Angeles County needs more such options.

But it’s Gascón’s election that provides the greatest opportunities for meaningful bail reduction and pretrial reform. The incoming district attorney can be more selective about the people he chooses to charge, and thereby ensure that his office’s resources are directed toward the most dangerous defendants, and that L.A.’s jails are not filled with people who would be out if only they had the money.

He also immediately becomes the new kid on the block — the one whom the supervisors, the police and the judges will blame for any increases in crime. That of course makes his new job politically hazardous, but it also gives him a measure of power to impose enlightened pretrial policies and to stand behind them. We’re hoping that he does. That’s the reason — one of them, anyway — that Los Angeles voters elected him.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.