Navigating the complexities of race in L.A. — and in The Times’ newsroom — as a young, Black reporter

I sidled into journalism fresh out of college in 1976, with a job at a weekly newspaper devoted to covering Cleveland’s Black community. We were “Negroes” in its pages back then. I wrestled with our elderly Black publisher over that, but he wouldn’t give in. “Negro” was a respectable label for a generation accustomed to settling for “colored.”

When I moved to Los Angeles three years later and joined The Times, I felt liberated from that kind of old-fashioned thinking. I’d gone from being one of only two Black reporters on the staff of Cleveland’s afternoon daily to being part of a diverse group of young reporters, hired to staff new sections covering Los Angeles’ multicultural suburbs.

I’d grown up in Cleveland, a city where the races were separated by the Cuyahoga River — white people on the west side, Black people on the east. I arrived here at 24, never having known anyone who wasn’t Black or white. The polyglot dynamic I encountered both fascinated and bewildered me.

Hunting for an apartment near my office in Van Nuys required me to calibrate the new racial dynamics. One landlord who’d spoken to me eagerly on the phone slammed her door in our face when my husband and I showed up Black. A few blocks away, another tried to entice us to move in by declaring proudly that “we don’t rent to Mexicans,” as if that was a selling point.

Our reckoning with racism

As the country grapples with the role of systemic racism, The Times has committed to examining its past. This project looks at our treatment of people of color — outside and inside the newsroom — throughout our nearly 139-year history.

That process signaled just how complicated navigating my new city might be. Where exactly did Black people fit in Los Angeles’ racial hierarchy? What would I need to know to cover this region? How sensitive to racial issues would The Times’ management and reporters be?

I asked myself those questions again and again during my decades at The Times.

On my first Saturday shift in Metro — a testing ground for young reporters hoping for promotion — I had to write a two-paragraph brief about a man killed in a robbery in East Los Angeles. I took the info from an LAPD officer over the phone, then typed up my story, in which I identified the victim as Hosé rather than José. That’s how unfamiliar Spanish was to me. The editor that day was Mexican American; he was appalled at my ignorance.

That was one mistake I wouldn’t make again. But there would always be landmines ready to explode in this diverse and divided city, whose liberal outlook today is at odds with its fractured history.

I realized in the early 1980s, from my perch living in and writing about the San Fernando Valley, that the Los Angeles Times didn’t seem to know or care much about the Los Angeles south of the 10 Freeway. All I could glean from reading our coverage was that Watts was a scary place, awash in poverty, crime and degeneracy.

But when I’d drive down from Van Nuys to take my measure of South L.A., the community I saw didn’t look dangerous to me. Its people, its rhythms and its routines felt comfortably familiar: the small pastel-colored houses with neat frontyards, the smell of meat on backyard grills, the narrow streets clogged with the raucous play of neighborhood kids.

Unlike in the Valley, no one was ever too busy to talk to a friendly reporter. I’d return home from my forays with homemade peach cobbler and armfuls of tropical flowers that homeowners yanked from their yards in Watts to be planted in mine in Van Nuys.

When I moved up to the paper’s Metro staff a few years later, I was eager to share that perspective with readers. And in the process, I saw firsthand how stereotypes can develop and infiltrate a newsroom, stigmatizing entire communities.

I remember writing about a food giveaway by a charity in South L.A. in the mid-1980s. One of our most experienced photographers was supposed to meet me outside a local church, where hundreds of residents, almost all of them Black, were lined up on the sidewalk. I was 30 minutes into interviewing them, and the photographer still hadn’t shown up.

I found a pay phone, called the newsroom and found out the photographer had been there the whole time — circling the block in his car, afraid to get out, convinced that a riot was about to erupt.

He was a white journalist who’d covered the Watts riots more than 15 years earlier. That experience apparently still haunted him. Where I saw an orderly crowd of seniors and families, he saw a volatile mob to be.

How, I wondered, could two people viewing the same scene interpret it so differently? Was our vision circumscribed by the color of our skin? Or was the newsroom polluted with racism?

Over time I have learned that both of those things can be true.

•••

Less than two years into my tenure at The Times, the newspaper’s facade of racial objectivity cracked in a very public way.

“Marauders From Inner City Prey on L.A.’s Suburbs,” screamed the headline of a front-page story in the summer of 1981. The article warned readers that dangerous bands of “young men desperate for money are marauding out” of Los Angeles’ ghettos and barrios “to prey upon the suburban middle and upper classes, sometimes with senseless savagery.” With overheated language, hoary stereotypes and dog-whistle innuendo, it suggested that “ghetto families” were breeding super-predators, intent on robbing and raping their way through the city’s good white neighborhoods.

A note to readers that accompanied the “marauders” article proclaimed it an insightful investigation “of an emerging phenomenon in America: the permanent underclass.”

Permanent underclass. That characterization particularly stung. In a country built on the lore of bootstrap success, were we to be stranded on the lowest rung of society for all time?

I was one of a dozen or so Black journalists at The Times back then. We were angry, disappointed and shocked by the article’s incendiary tone. There were so few stories in The Times about everyday life in Black Los Angeles; this felt like an outrage to us.

And that outrage registered among journalists across the country. The National Assn. of Black Journalists would later deem the piece the “most objectionable news story” of the year; “reckless … preposterous … unpardonable journalism.”

Most of us had grown up in middle- or working-class neighborhoods, but lives like ours rarely showed up in The Times. This outsize focus on a community’s criminal fringe seemed crafted to mislead and inflame. We wanted to address that, so we asked to meet with Times Editor William F. Thomas.

Thomas was cordial and unruffled when we met. I remember him going around the table, asking each of us to introduce ourselves and tell him where in the paper we worked. I realized that most of us were ciphers to him.

Still, he listened patiently to our concerns: No Black journalists had been involved in the project; most of us had been toiling in small suburban bureaus for years; Metro reporters rarely ventured into South L.A.

Almost 40 years have passed, and my memories beyond that are vague. When I called former colleagues this summer to see what they recalled, we all remembered little about the editor’s response. We’d tried to explain why it was important to have Black reporters and editors involved in coverage about Black life in L.A., but Thomas seemed nonplussed.

“That showed me they had no context, no experience with African Americans,” recalled Pamela Moreland, who in 1981 was the only Black reporter in The Times’ business section. Without “a Black person in the room” when the story was conceived, reported, written and edited, “there was no one to say ‘let’s balance this’ or ‘let’s rethink that.’”

Looking back, nothing much changed after our audience with the boss. For a time, the uproar over the story — in the community and the newsroom — did spur efforts to broaden coverage of South Los Angeles. But attention soon flagged. On the rare times I crossed paths with Thomas after that, he called me “Pamela.”

•••

In the decades following the “marauder” piece, the racial evolution of the Los Angeles Times took shape in fits and starts, stumbles and recoveries.

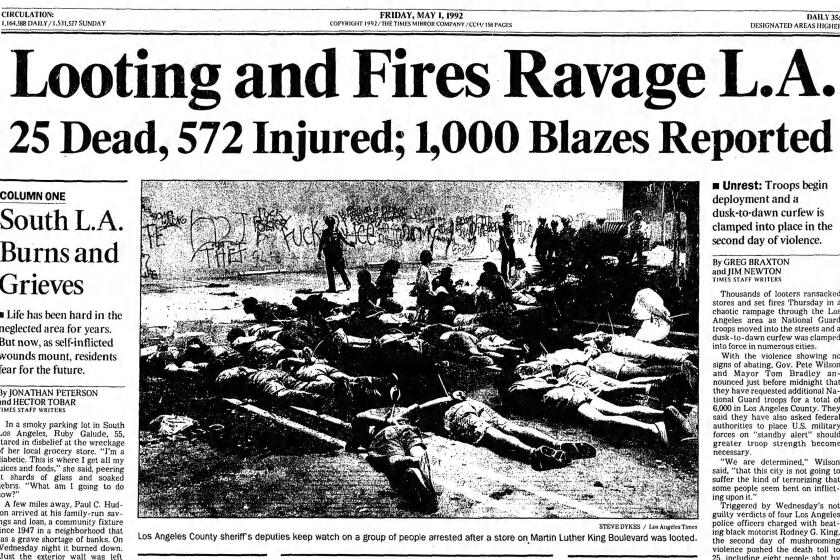

We made a decades-long commitment to diversity with the creation in 1984 of an internship and apprentice program known as MetPro, which launched the careers of hundreds of journalists of color, who are now doing important work across the country. We won Pulitzer Prizes for a series exploring the lives of Latinos in Los Angeles in 1983 and for our coverage of the Los Angeles uprising in 1992.

But we still have blind spots and potholes in our path. We have not yet developed a culture where inclusivity — in our coverage and in our newsroom — feels natural and authentic.

The racial crisis engulfing the nation is shining a light once again on The Times’ shortcomings, and the fix won’t be quick or easy or comfortable.

I know that because we’ve been at this juncture before, in the spring of 1992. During the chaotic weeks after a Simi Valley jury acquitted LAPD officers involved in the beating of Rodney King, rage erupted in the streets, and racial tensions splintered our newsroom.

It’s hard to cover a crisis when you’re in crisis yourself. We’re feeling that pressure now, just as we felt it 28 years ago.

Back then, young reporters of color had been summoned from suburban bureaus and dispatched to hot spots in Koreatown and South Los Angeles. They worked long hours in dangerous conditions, absorbing the energy and anger of the streets.

But when they made it back to the newsroom, they were often ordered to hand their notes over to a rewrite team — made up primarily of white men — that would cobble together the versions of the uprising that readers would see.

Those young folks, whose presence made our paper’s diversity stats look good, realized then that they were not deemed valuable enough for much beyond legwork. “Cannon fodder” is how they described themselves, as resentment built and exhaustion set in.

In response, the newsroom held a “town hall” session to talk the tensions out. There were tears, shouting, pleas, apologies, angry diatribes. I remember feeling drained by the intensity but heartened by our willingness to honestly discuss our grievances — then plunge back into covering a city that was violently airing its own grievances in the streets.

I realize now that I learned a lot during my newspaper’s journey. I’ve risen through the ranks, in part because I’ve learned to trust my voice. The process of grappling with demons can be empowering.

Still, it’s not always easy to be a reporter of color when your default audience and the institutional perspective are perceived to be white.

It’s hard on the psyche to be perpetually reminded that some people won’t ever respect you, yet your job is to try to understand and tell their stories, too.

That burden feels especially acute right now, given the turmoil of these last few months. I was surprised by how strongly my emotions surfaced when I reread the “marauders” piece recently, for the first time since the 1980s. Heartache hit me harder than anger this time around.

The story had been written by journalists I admired and edited by people whose judgment I was expected to trust. Yet none of them had been bothered by the caricatures they’d created: the archetypes of evil, the vile stereotypes, the dark-skinned “marauders” driven by greed, evil and lust.

The drumbeat of war allusions — marauders, invasions, predators, prey — agitated me. The repetition of the N-word, in quotes coaxed from hoodlums, assaulted my sensibilities. Even the tone-deaf acknowledgment by a character in the story that “Many of the people in Watts are good citizens” set me on edge.

It took me a few tries to make it through the piece. When I took a break, I’d leave the printout on my dresser, and my heart would race from anxiety whenever I glanced at it.

It reminded me how undervalued the Black community has been, how naive and hopeful I was back then.

This is not the same newspaper I joined in 1979. We’re wiser, more diverse and better connected to readers. I’m proud of this new generation of newsroom firebrands, who aren’t willing to sit quietly on the sidelines.

But we’re also facing industrywide challenges, including dire economic realities and the formidable task of bridging differences within our own community related to race, gender, generation, sexuality and ethnicity.

Still, we recognize our responsibilities. We’re not giving up; we’re raising the bar. We know we’re at an inflection point, in our nation and in our newsroom.

The power dynamic is shifting. And the status quo, which has elevated some but ignored too many others, is not acceptable anymore.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.