Editorial: The 1980s crack epidemic was a fork in the road. America chose racism and prisons over public health

What if the nation had met the crack epidemic of the 1980s with healthcare rather than with police and prison? How much more prepared might we have been today for a deadly viral pandemic, and how much more resilient in the aftermath, had we built out a public health infrastructure with treatment clinics, housing and other resources and supports aimed at restoring the health of American neighborhoods?

What if we had recruited, trained and adequately paid a generation of clinicians, physicians, nurses, researchers, peer counselors and educators to deal with the drug crisis instead of buying tanks and armored cars for police and sending them into neighborhoods suffering the physical and social consequences of cheap crack cocaine?

The 1980s were our fork in the road. The path we chose led directly to the nation we now inhabit, overwhelmed by serious illness, fear, anger, mutual mistrust and a level of inequity and incompetence that mocks our self-image as Americans.

To know what to do now, it’s essential to remember what we didn’t do then.

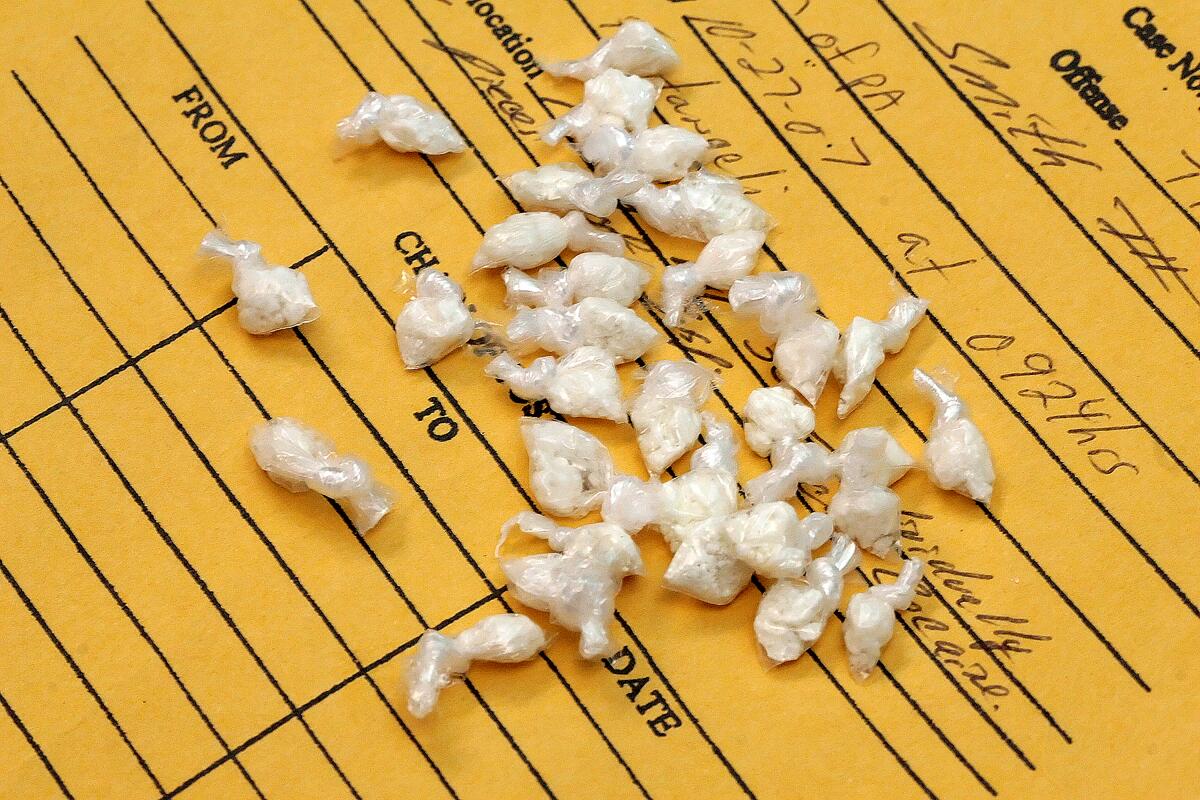

Smokable cocaine “rocks” first appeared on the streets of American cities in 1981. Cheaper than powder cocaine and highly profitable for suppliers and dealers, the drug was associated with an alarming increase in hospital emergency room visits. Nevertheless, the early governmental response was neglect.

As the ’80s wore on, though, rock cocaine became known as “crack,” and it wormed its way into the popular imagination as a fearful substance that threatened to destroy the nation. The anti-crack frenzy preceded the real epidemic, which took off in the middle of the decade when Congress made penalties for possessing the substance 100 times greater than for similar amounts of powder cocaine. The rationale was specious: that crack was more addictive, an assertion that subsequent studies demonstrated to be untrue. Crack possession may have been targeted because it was associated in the public mind with African American users, and powder with well-to-do whites. The race-tinged national panic over crack reshaped and reinvigorated the “war on drugs” that President Nixon declared in 1969.

Two companion public health disasters followed in quick succession. The first was violent crime, as crack profits lured street entrepreneurs and gangs. Competition became deadly. The murder rate for young Black men doubled.

The second was the law enforcement response and what later became widely known as mass incarceration. Black communities that for decades had suffered from official neglect suddenly saw astounding investment of public resources — in the form of violent policing.

In Los Angeles, LAPD Chief Daryl Gates ratcheted up the force, deploying armored cars to break down so-called crack houses and conducting massive weekend raids that resulted in the arrest of hundreds of young Black men, whose cars were impounded and often ransacked by the time they were released from jail — without charges — on Monday morning.

Black men who were indeed charged were typically sentenced under new crime laws carrying shockingly stiff mandatory prison terms.

Health officials consider waves of murder, male depopulation of communities and racism to be public health crises equal to drug or viral epidemics. Health is intimately tied to social and economic opportunity, the quality of our schooling, the safety of our workplaces, the cleanliness of our air and the readiness of family, friends, neighbors, peers, parishioners and officials to render aid when any of us is in crisis.

The disparity in the quality of those social determinants of health is readily identifiable on maps that display life expectancy by ZIP Code. In some parts of Los Angeles, a stretch of three miles means a difference of 13 years in average lifespan.

Instead of fixing that disparity, the police-and-prisons response exacerbated it.

When the savage beating of Black motorist Rodney King by LAPD officers in 1991 was caught on videotape, African Americans in Los Angeles were hopeful that the rest of us would finally see what they had been suffering through the crack epidemic and the violence and harassment that ensued, and would finally do something about it. Instead, a year later, the officers were acquitted. The angry outburst that followed was a reaction not just to the King beating and LAPD impunity, but to a decade’s worth of serious health and social needs being answered with law enforcement “solutions.”

The crack epidemic was an opportunity lost. The legacy of the 1980s could have been a service infrastructure that provides people in crisis a place to go for care and a set of enforceable health quality standards.

But instead we built and packed prisons. Now, 28 years later, those institutions have become the nation’s leading centers of novel coronavirus infection.

The disease has so far sickened nearly 2 million people in the U.S. and killed well over 100,000, with the death toll being much higher in communities of color, including Black neighborhoods — predictably so, considering those maps that measure and depict community health and resilience.

The May 25 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, like the beating of Rodney King, represented more than just a shocking example of police violence. The killing and the angry and sometimes violent protests that followed sum up yet another generation of failed policy and imposed inequity.

We are called to respond differently this time. We must do now what we failed to do then: Build a system of care that fosters health and justice, and deconstruct the costly police-and-prisons infrastructure that we foolishly built instead.

We need not start from scratch. Los Angeles County helps people coming home from jail or prison reunify with their families and get jobs, housing and care. The Office of Diversion and Reentry — housed, it’s important to note, in the Health Department — is the leading edge of a broader care-first, jails-last program that, if built out as envisioned by frontline service providers and county workers, could be the system that we should have built more than three decades ago. It could be a model for the nation.

The L.A. County Board of Supervisors adopted a framework for the care-first program, formally known as Alternatives to Incarceration. But then came the current health crisis, and implementation has stalled. It would be ironic — and tragic — if the program is mothballed because the pandemic and the reaction to Floyd’s killing turn the county’s attention elsewhere. Might we, in 30 years, look back again at the road we should have taken but didn’t?

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.