Charles Munger, who helped build one of the greatest fortunes in U.S. history, has died

Charles Munger helped build one of the greatest fortunes in U.S. history, but he often explained his success in terms that sounded deceptively uncomplicated.

“Take a simple idea and take it seriously.”

“Load up on the very few insights you have instead of pretending to know everything about everything at all times.”

And above all, he stressed the need for patience and a long-term investment view — an approach that has vanished from much of Wall Street in recent decades.

In his trademark curmudgeonly style, Munger advised investors to take stakes in a relative handful of great companies and then “just sit on your ass.”

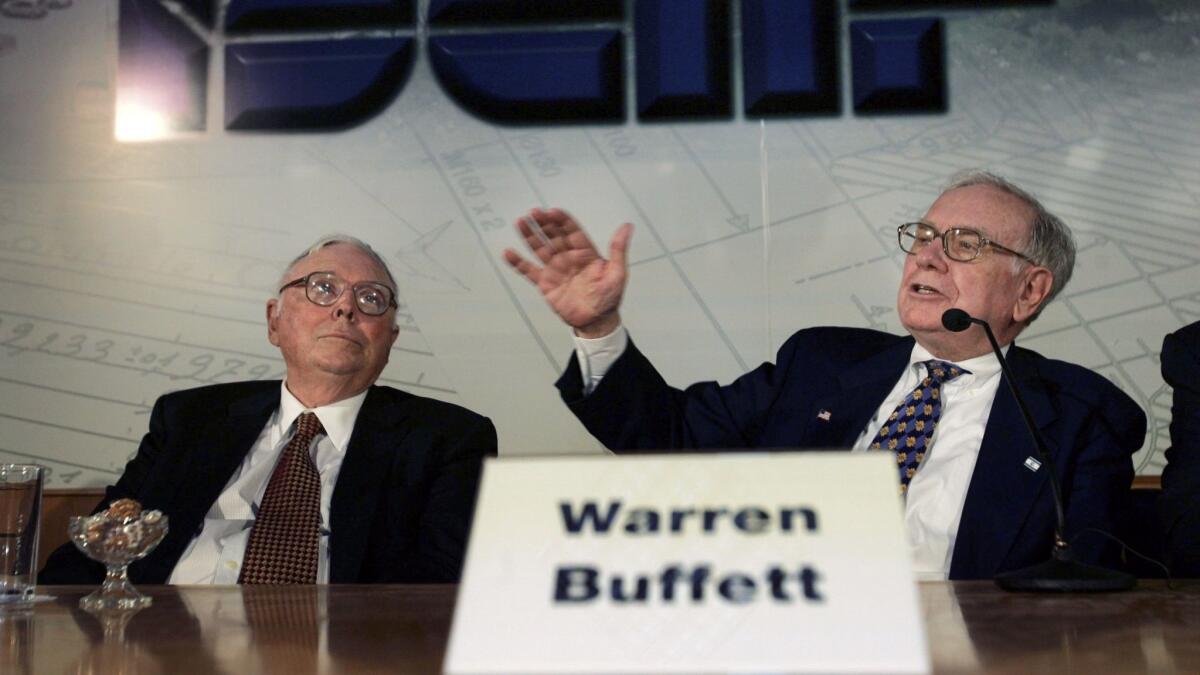

Munger, the longtime investment partner of billionaire Warren E. Buffett, died Tuesday at a California hospital, according to Berkshire Hathaway, where he was vice chairman. He was 99.

“Berkshire Hathaway could not have been built to its present status without Charlie’s inspiration, wisdom and participation,” Buffett said in a news release.

Though born in Omaha, like Buffett, Munger lived in Los Angeles most of his life. And for the most part, he shunned the media spotlight that Buffett often relished.

However, with a net worth that Forbes estimated at $2.6 billion upon his death, he was able to make a big impact with his philanthropy both locally and elsewhere.

He was a longtime benefactor and board chairman of Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles. He also funded a science center at Harvard-Westlake School in L.A. and a research center at the Huntington Library.

In higher education, Munger said he wanted to foster more dialogue and mixing of ideas on campus. In 2013 Munger donated $110 million in stock for a graduate residence at the University of Michigan. He gave $43.5 million in 2004 for a graduate residence adjacent to Stanford Law School.

But it was a 2016 donation that led to perhaps the biggest controversy of his career. He pledged $200 million to build new dorms at UC Santa Barbara, which had a severe shortage of student housing.

He pushed for the construction of an 11-story warehouse-size building that would feature 4,500 beds in small rooms — similar to but larger than the Michigan dorm. Unveiled in 2021, the massive UCSB structure was dubbed “Dormzilla” by its critics, and the university is reportedly considering alternatives.

Munger sometimes was described as Buffett’s “sidekick,” but that grossly understated his influence on Buffett, who is six years his junior.

Berkshire, with more than $1 trillion in assets, owns such well-known brands as insurance company Geico, the BNSF railroad, See’s Candies, Fruit of the Loom and Dairy Queen.

After meeting Munger at a dinner party in Omaha in 1959, Buffett — then an ambitious but novice investor — said he quickly realized that there was “only one partner who fit my bill of particulars in every way: Charlie.”

Buffett’s wife, the late Susie Buffett, once wrote of the two men that “both thought the other was the smartest guy they ever met.”

In the last few decades Munger’s name has become better known, at least among serious investors, as he shared the spotlight with Buffett at Berkshire’s annual shareholder meeting. The two became a nightclub act of sorts, peppering sage investment advice with one-liners that kept the crowd of thousands enraptured.

One of Munger’s most famous zingers encapsulated his frequently acerbic wit: “I’m right, and you’re smart, and sooner or later you’ll see I’m right.”

Charles Thomas Munger was born on Jan. 1, 1924, in Omaha to Al and Florence Munger. His father was a lawyer, and his grandfather had been a federal judge.

As described by Michael Broggie in the 2005 book “Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger,” Munger’s family fared comparatively well during the Great Depression.

Still, young Charlie was expected to work. One of his first jobs was clerking — for $2 per 12-hour shift — at Buffett & Son, an upscale Omaha grocery run by Warren Buffett’s grandfather. But Munger never met the younger Buffett during their youth.

A voracious reader whose hero was Benjamin Franklin, Munger showed an aptitude for business early on when he began to raise hamsters to trade with other kids.

“Even at an early age, Charlie showed sagacious negotiating ability, and usually gained a bigger specimen or one with unusual coloring,” Broggie wrote.

After high school, Munger enrolled at the University of Michigan as a math major, but he left in 1943 to join the war effort. He enlisted in the Army Air Forces and was trained in meteorology at Caltech in Pasadena.

Though he lacked a bachelor’s degree, Munger in 1946 decided to apply to Harvard Law School. He was accepted after a family friend intervened.

Munger excelled at Harvard, graduating magna cum laude. His first law job was at Wright & Garrett in Los Angeles.

But in his personal life, Munger faced challenges. At age 21 he had married Nancy Huggins, a family friend. They divorced in 1953, when Munger was 29.

Shortly afterward the oldest of their three children, Teddy, was diagnosed with leukemia. He died at age 9.

In 1956 Munger married Nancy Barry Borthwick, a Stanford University economics graduate. They had met through Munger’s friend Roy Tolles. Borthwick had two sons from her first marriage. She and Munger had four more children together.

The size of the family was key to Munger’s fateful decision to shift career tracks from law to investing.

“Nancy and I supported eight children,” Munger said in 1996. “And I didn’t realize that the law was going to get as prosperous as it suddenly got.”

He put it another way to Janet Lowe, who wrote the biography “Damn Right! Behind the Scenes With Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger” in 2000.

“Like Warren, I had a considerable passion to get rich,” Munger told Lowe. “Not because I wanted Ferraris — I wanted the independence. I desperately wanted it.”

In 1962 Munger co-founded the L.A. law firm Munger Tolles & Hills (today known as Munger Tolles & Olson). But by then his investing pursuits were already taking up much of his time.

Though he began trading investment ideas with Buffett in 1959, from 1962 to 1975 Munger was mostly focused on building his own stock investment fund, Wheeler, Munger & Co., according to biographer Broggie.

Munger racked up strong returns in the fund, but, like most investors, he was hit hard in the deep bear market of 1973-74, amid the first Arab oil embargo.

After the market rebounded in 1975, Munger decided to stop directly managing money for others. Instead, he joined with Buffett in investing via the “holding company” concept: The two would buy businesses and make stock investments through a publicly traded company. They would control the firm by virtue of their large stake in it, but other investors could buy the company’s shares if they wanted to join in as essentially silent partners.

Their primary vehicle was Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Munger became vice chairman of the firm in 1978.

Munger also ran a smaller holding company, Pasadena-based Wesco Financial, which was majority-owned by Berkshire. It was merged into Berkshire in 2011. Separately, Munger headed Daily Journal Corp., an L.A.-based publisher of legal newspapers, including the L.A. Daily Journal.

But Berkshire’s success is what made Munger’s name synonymous with brilliant investing.

Buffett credited Munger with refining the former’s basic “value” approach to investing. Buffett was a devotee of Ben Graham, the father of the value school, which preached the discipline of buying shares only in companies that met rigid financial criteria.

Munger, however, convinced Buffett that a long-term investor could prosper by focusing on the very best companies — even if they didn’t meet all of Graham’s value requirements.

Munger’s approach was crystallized in his most famous investing maxim: “A great business at a fair price is superior to a fair business at a great price.”

Munger “expanded my horizons,” Buffett has said.

That, in turn, led to Berkshire’s purchases of huge stakes over the years in such blue-chip companies as Coca-Cola, American Express, IBM and Wells Fargo, in addition to the dozens of companies Berkshire owns outright.

Munger owned only a small fraction of Berkshire stock, but the success of Berkshire Hathaway made him a billionaire anyway.

Later in life, Munger at times became almost apologetic for his financial success. In a 1998 speech he bemoaned the allure of Wall Street for talented young people, “as distinguished from work providing much more value to others.”

“Early Charlie Munger is a horrible career model for the young, because not enough was delivered to civilization for what was wrested from capitalism,” he said.

He was an outspoken critic of excessive executive pay. He and Buffett drew annual salaries of $100,000 at Berkshire, a pittance compared with what most top Fortune 500 executives are paid.

Though a self-described conservative Republican (in contrast to Buffett, a Democrat), on some issues Munger defied the conservative stereotype. He was a longtime supporter of Planned Parenthood, for example, and fought in the 1960s to legalize abortion.

“I’m more conservative, but I’m not a typical Colonel Blimp,” Munger said in 1996, referring to the jingoistic, reactionary British cartoon character.

Munger’s wife, Nancy Barry Munger, died in 2010.

He is survived by eight children and stepchildren, 15 grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

Petruno is a former staff writer. Times staff writer Laurence Darmiento contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.