Ken Balcomb, friend to the orcas who helped end their captivity, dies

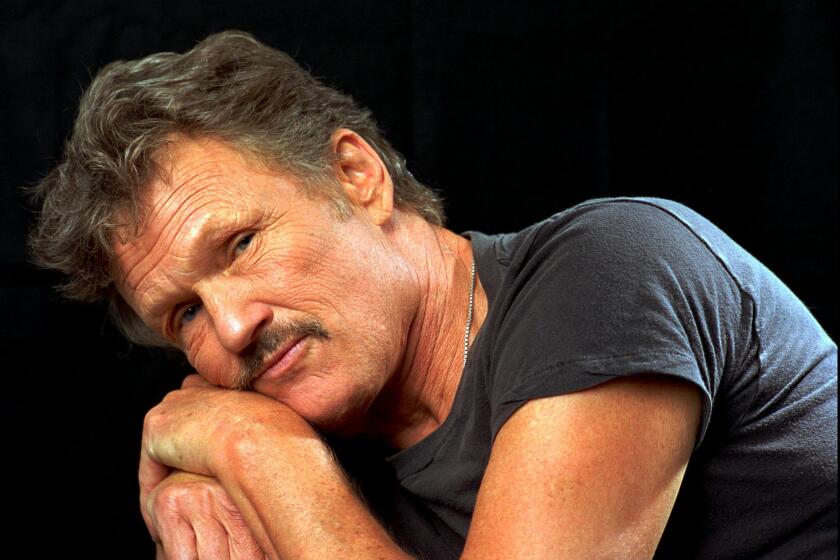

Ken Balcomb, a researcher who spent nearly five decades studying the Pacific Northwest’s charismatic and endangered killer whales — and whose findings helped end their capture for display at marine parks in the 1970s — died at a ranch on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula.

Surrounded by friends, Balcomb died Thursday at 82, according to the Center for Whale Research, the organization he founded. The center bought the ranch along the Elwha River two years ago to protect spawning grounds of Chinook salmon, which is prime food for orcas.

The cause was prostate cancer, the Seattle Times reported.

“Ken was a pioneer and legend in the whale world,” the center said in a message posted on its website. “He was a scientist with a deep-rooted love and connection to the whales and their ocean habitat. He inspired others to appreciate both as much as he did.”

Balcomb first worked as a whale biologist for the federal government in 1963, after graduating from UC Davis. He served in the Navy during the Vietnam War as a pilot and oceanographic specialist.

He began his life’s work with orcas in 1976, and his research two decades later helped raise alarm that the whales were starving from a lack of salmon — which formed the basis for their listing in 2005 under the Endangered Species Act.

In the 1960s and 1970s, dozens of Pacific Northwest whales were caught for display in theme parks such as SeaWorld. At least 13 orcas died in the roundups, and the brutality of the captures began to draw public outcry and a lawsuit to stop them in Washington state.

The whale-capture industry argued that there were many orcas in the sea, and that some could be caught without threatening the species. The Canadian and U.S. governments sought to conduct surveys to get a better sense of the animal populations.

Following the lead of Canadian researcher Michael Bigg, who pioneered the use of photographic identification of individual orcas by the shape of the white “saddle patch” by their dorsal fin, Balcomb in 1976 established an annual survey of the whales.

Though Bigg’s findings had largely been doubted, Balcomb confirmed that there were only about 70 remaining orcas in the Pacific Northwest — after about 40% of the population were taken into captivity or killed during roundups.

Balcomb continued the survey each year, following the orcas with his binoculars in a boat, photographing them and constructing family trees of the three pods of Southern Resident killer whales.

Even after other researchers lost interest in the whales in the 1980s, Balcomb persisted, said Brad Hanson, a wildlife biologist with NOAA Fisheries who first met Balcomb in 1976.

Balcomb founded the Center for Whale Research, with little in the way of financial support. He documented the mid-1990s recovery of the population to 97 whales before its sudden collapse to fewer than 80 in the following years — a decline that Balcomb observed and which formed the basis for orcas getting endangered status.

“I don’t think we would have known if it hadn’t been for Ken,” Hanson said. “He laid the foundation for and significantly contributed to the understanding of these animals we have today. We just wouldn’t be where we are without Ken’s research.”

An eccentric and sometimes gruff scientist with a gray beard and a weathered look, Balcomb had a single-minded devotion to the whales, with their bones displayed around his San Juan Island home in Washington state. On a stereo, he often listened to the clicks and whistles of passing whales through underwater devices sunk in kelp beds.

Northwest killer whales have gone from feared to adored to endangered. And some say the tours that depend on them are partly to blame.

He advocated for the breaching of four massive dams on the Snake River to restore salmon habitats, and he had little patience for politicians who dithered rather than act to save the whales. “I’m not going to count them to zero — at least not quietly,” he often said.

He served on Washington Gov. Jay Inslee’s orca recovery task force in 2018 but refused to sign its final recommendations, saying that they wouldn’t do enough to recover the whales.

One of Balcomb’s most public fights involved not orcas, but beaked whales. He was in the Bahamas in March 2000 when a beaked whale stranded itself in front of him. It was one of 17 marine mammals, mostly whales, stranded in the Bahamas that day. After trying with others to save as many as they could, he cut the heads off two whales that died and had them frozen for study — he suspected they had been driven from the water by military sonar exercises happening offshore.

Another scientist conducted necropsies and CT scans, and found that the whales had bleeding in their ear canals. When federal officials demurred about the cause of the strandings, Balcomb held a news conference in Washington, D.C., and spoke out, blaming the use of a new generation of anti-submarine sonar technology.

He also accused the Navy and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of playing down the harm that sonar caused the whales in Washington state.

“Ken wasn’t shy about making his feelings known, based on the information he had collected and seen,” Hanson said. “I regularly got an earful about what we were or were not doing with regard to the whales.”

In 2020, the Center for Whale Research purchased a 45-acre parcel on the Elwha River called Big Salmon Ranch, where dams had been removed and Chinook salmon had returned to spawning grounds that had been inaccessible since the early 20th century.

“I was getting kind of tired of telling the story of whales declining, of fish declining,” Balcomb said. “I want to be on the good side of a story.”

Balcomb is survived by his son, Kelley Balcomb-Bartok; grandchildren Kyla and Cody Balcomb-Bartok; and brothers Howard Garrett, Scott Balcomb and Mark Balcomb, the Seattle Times reported.

Garrett and his wife, Susan Berta, run the Orca Network, a nonprofit advocacy organization based on Whidbey Island.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.