SAUSALITO, Calif. — When Bill Keener started working at the Marine Mammal Center as a field biologist in the 1970s, there were no whales or dolphins in San Francisco Bay. The waters east of the Golden Gate Bridge were chock- full of life — sea lions and harbor seals galore — but not a cetacean to be seen.

Starting in the late 2000s, things began to change.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

There are now four cetacean species living in or regularly visiting the busy waters east of the Golden Gate — harbor porpoises, gray whales, humpback whales and bottle-nosed dolphins.

Yet Keener and other marine researchers aren’t sure if the animals’ presence is a sign of ecosystem health and rejuvenation or a portent of planetary disaster. And in each case, the story is a little different.

Regardless of the cause for their return, they’re growing increasingly worried that as the numbers of these charismatic megafauna grow, so too does their risk of injury and death in these high-traffic waters.

“We have one of the busiest ports on the West Coast, 85 private and recreational marinas, high-speed ferries and lots and lots of vessel traffic,” said Kathi George, director of cetacean conservation biology at the Marine Mammal Center. “These animals are showing up in places where it’s a cause for celebration, but it’s also a cause for concern.”

Harbor porpoises

Take, for instance, the harbor porpoises.

Keener said these friendly, blunt-nose, dolphin-like animals had been a permanent fixture in the bay for thousands of years. That is, until they weren’t.

Evidence from the Ohlone shell mounds — large middens of discarded bones and shells found throughout the Bay Area — indicates that while they were once abundant, they either died or fled en masse in the 1940s as the U.S. geared up its defenses during World War II. Fearful of enemy submarines, the Navy stretched a large steel net across the bay to keep underwater boats from sneaking in.

Whether it was the physical presence of the netting, or the underwater clanging and ruckus it made (which Keener has said was likely really loud), the porpoises disappeared for more than 60 years.

What brought them back isn’t entirely clear. It may have been due in part to the effectiveness of gill-net bans in the 1980s, which allowed the porpoise population to grow. They also may have been following food sources. And once the porpoises entered, they recognized it as a pretty good place to settle down.

Whatever brought them in, they’ve stayed — and they’re a common site splashing and diving along the edge of Kirby Cove, or around the Point Diablo Lighthouse peninsula.

Humpback whales

The humpback whales may also be a good news story — although, unlike porpoises, they probably were never permanent residents of San Francisco Bay. There is no evidence of them in the shell mounds and no historical reports of them inside the Bay.

But they have been consistently present off the coast — migrating from their wintering grounds in Mexico and Central America to California in the summer, where they gorge on fish and krill along the coast. However, as a result of whaling, their numbers had fallen to roughly 2,000 by the early 1970s.

Since then, however, their population has ballooned to 20,000.

“That’s what happens when you stop hunting them,” Keener said.

And in 2016, for the first time anyone could remember, an influx of humpbacks came into the bay, following a dense school of anchovies. Ever since, they’ve been regular visitors during the summer.

Gray whales

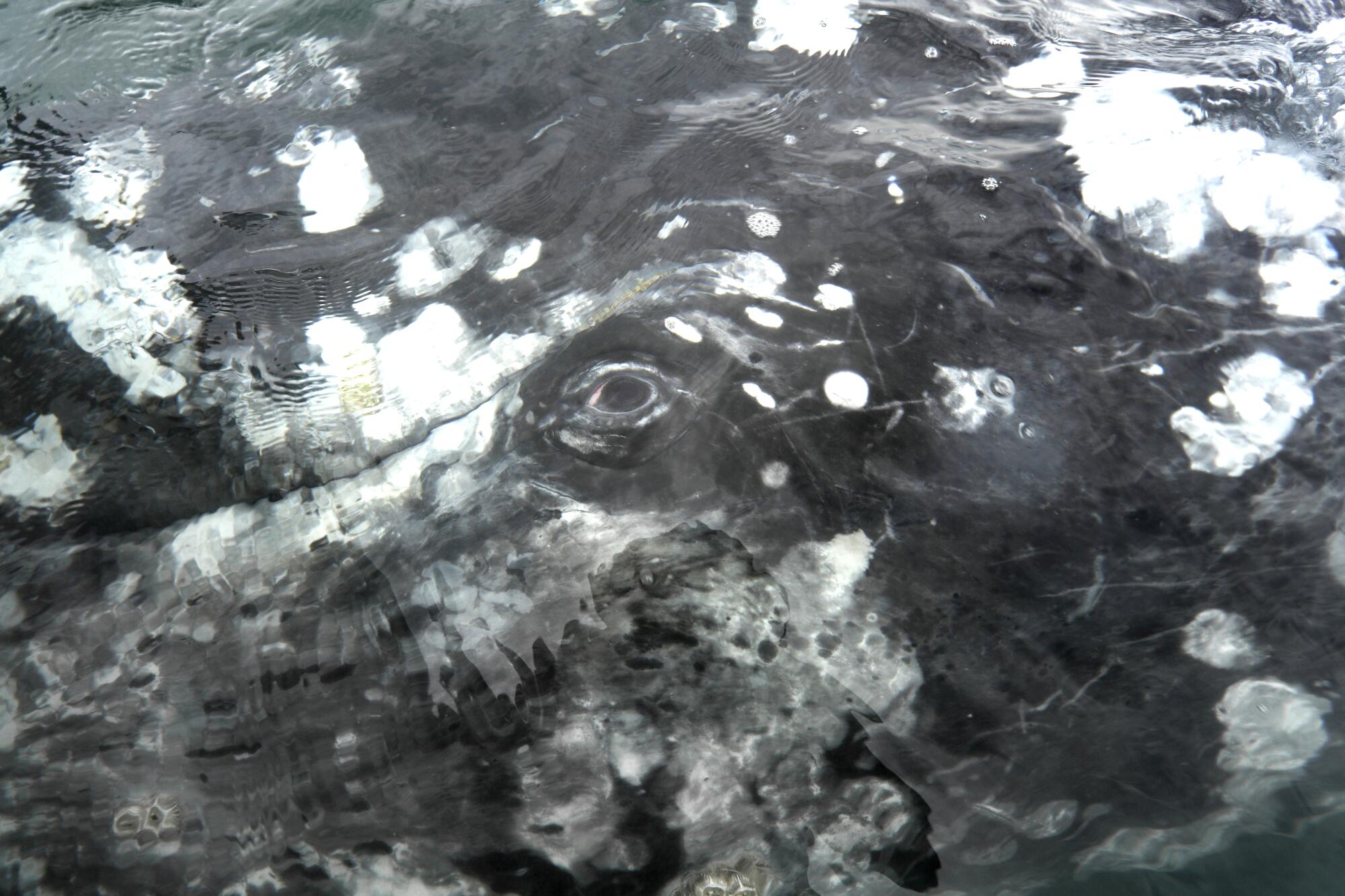

The story of the gray whales might be a little more ominous.

As with the humpbacks, there is no historical record of these singing whales having any major historical presence in San Francisco Bay — save for one skeleton discovered in a 2,500-year-old shellmound and one historical report from Spanish missionaries of gray whale spouts in the bay.

But in 1999, they began showing up — just as an unusual mortality event got underway that, by its end in 2002, nearly halved the eastern Pacific population of gray whales.

After the mass strandings had subsided and the population once again began to grow, they weren’t seen again — save one or two a year — until 2019, when another massive mortality event occurred.

This time, however, the whales seem to be sticking around. This year, there have been 16 sighted in the bay — including one that died.

But this time, they’re doing something Keener and others say is somewhat unusual: They’re feeding.

Typically, gray whales feed only in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters during the summer months, when the cold seafloor is filled with life and millions, if not billions, of small shrimp-like critters that the whales scoop up in their enormous jaws. The whales feast all summer long, and only then embark on a 6,000-mile journey south to Mexico, where females calve and nurse their young in the warm and protected inlets along the Baja Peninsula.

Once they leave the Arctic, they don’t feed again until the following year.

But researchers and observers have seen them diving and searching for food in San Francisco Bay — as well as lunge-feeding, a humpback whale style of eating in which they open their mouths and lunge at the water’s surface to grab fish and other organisms.

And though that could be a concerning sign — that their usual feeding grounds are no longer productive, possibly as a result of the extreme climatic changes taking place in the Arctic and the ocean — Keener likes to see it in a more positive light.

The feeding behavior is “an indication that these guys probably were hungry, and they’re looking for other food sources,” he said, citing his colleagues’ necropsy research on stranded whales that showed a large number were malnourished. “But it also shows they’re resilient, and that they can change their behavior and do something they’re not known for. That is actually a good sign.”

Industrial activity has added up to 15 decibels of noise to the Santa Barbara Channel, new research has found. Hear the difference.

Keener noted the animals had survived past dramatic swings in the climate, such as during the Ice Age. And this flexibility is probably what “kept them going when they were dealing with ice ages, all kinds of environmental changes to their feeding grounds over the last several thousand years.”

He said it bodes well for the species as climate change roils vast ecosystems across the planet.

And, he said, their work is showing that it isn’t just random whales stopping in during their migration. Some individuals are returning again and again, leading he and his colleagues to think that “some of them are learning our local area, figuring out how to navigate and find food. You know, just live in our area.”

When a sea lion is found stranded anywhere between Long Beach and Malibu, chances are the Marine Mammal Care Center will help with its rescue.

Bottlenose dolphins

The bottlenose dolphins that now visit with frequency may also be one of those silver-lining stories.

Generally considered a warm water species more common to Southern California, they started coming into San Francisco Bay — like the porpoises — around 2008. Their range started creeping north around the 1980s (initially after an intense El Niño event), and by 2000, they were seen with relative frequency in the coastal waters near the bay.

There are no resident groups inside the bay, Keener said, but “they do visit.”

Keener said the Marine Mammal Center has compiled a local photo-identification catalog that includes 120 adults. Some of them have been identified as 1980s-SoCal-dwelling dolphins. He said the dolphins get around — with one well-known female spotted cruising the waters of Monterey in the spring, and just last week hanging around Sonoma County’s Sea Ranch.

“She really gets around, and that is normal,” Keener said.

The big picture in a busy Bay

And though this observer of a quickly changing ocean and its occupants’ atypical behavior remains hopeful on a grand, existential scale, he — and others — are worried about the more immediate safety of these charming sea creatures in the busy shipping lanes of San Francisco Bay.

None of these animals are on the endangered species list, he said, but that doesn’t keep him and his colleagues from worrying, “particularly if they come into the bay, where it’s dangerous for them. There’s just so much ship traffic.”

George, of the Marine Mammal Center, said there are vast stretches of water throughout the Bay Area where there are no voluntary vessel slow-down areas — a tactic that conservationists, ports and shipping companies have used elsewhere to decrease the likelihood of ships striking cetaceans.

Our oceans. Our public lands. Our future.

Get Boiling Point, our new newsletter exploring climate change and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But George said she and other conservationists are working on it with the Harbor Safety Committee, which she said has been receptive and is working to formalize plans to protect the animals.

“I’m just so excited over the collaborations that are taking place and that are continuing to develop,” she said.