Desmond Tutu, cleric who campaigned against apartheid in South Africa, dies at 90

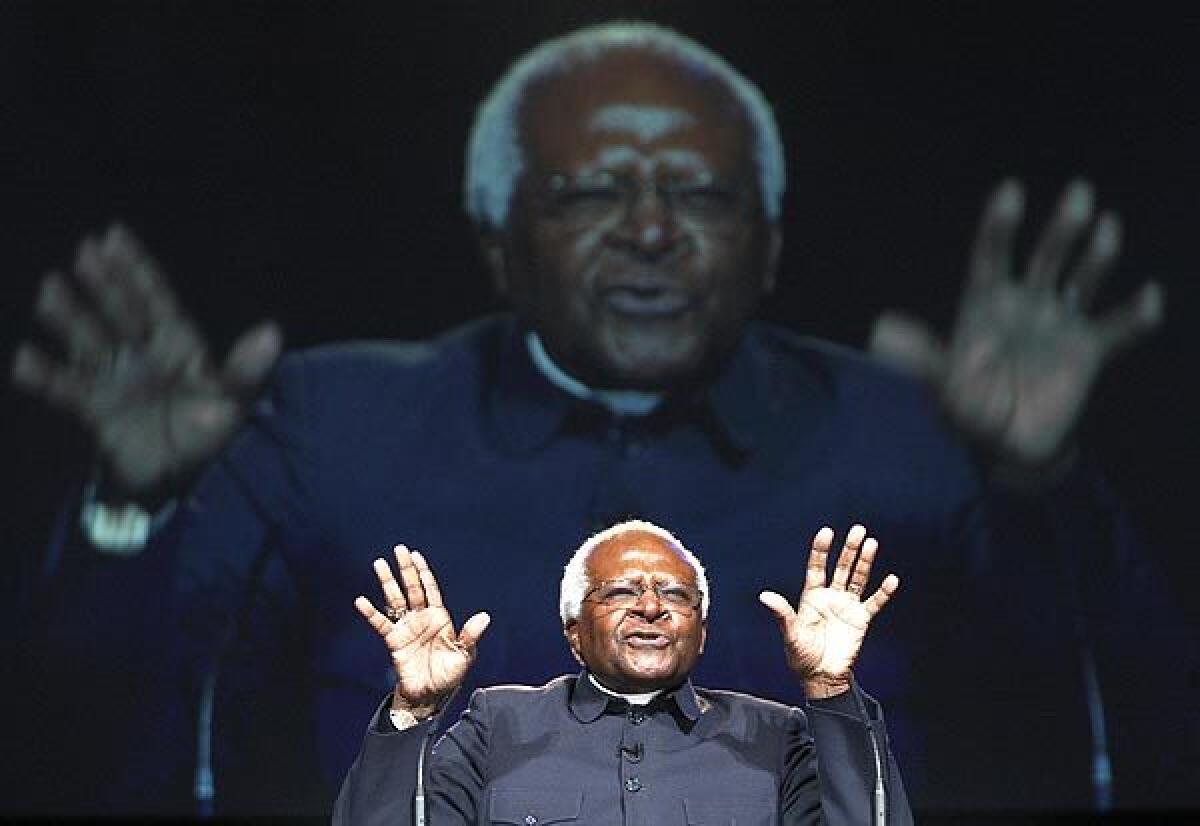

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — Desmond Tutu, the former Archbishop of Cape Town who won the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize for his impassioned campaign against apartheid in South Africa while Nelson Mandela languished in prison, died early Sunday.

Tutu, 90, died of cancer at a care center in Cape Town, the Archbishop Desmond Tutu Trust said in a statement. He had been diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1997 and had been hospitalized several times in recent years.

A moral beacon in a deeply troubled land, the impish priest in the purple cassock stood for decades as an inspiring symbol of courage, dignity and hope in a nation that at times seemed doomed to civil war. His fervent pleas for peace and racial justice, along with his irrepressible sense of humor, were a constant balm to a country on the edge.

Tutu held a unique place in apartheid-era South Africa, and he used his stature as an Anglican prelate to navigate violent crosscurrents. He wept at funerals for victims of apartheid, risked his life to stop violence by Black protesters, and defied death threats by white people for leading the international campaign to impose economic and cultural sanctions against the white minority regime.

Then, after the success of the anti-apartheid movement, he served as a goad to the governing African National Congress, upbraiding leaders over corruption and failure to adequately address the nation’s widespread poverty.

With the exception of Mandela, who died in December 2013, few people have so influenced modern South Africa’s turbulent history as the jovial archbishop, who often wore a T-shirt that read “Just Call Me Arch” under a jaunty fisherman’s cap.

He shrieked with joy when South Africans lined up peacefully to vote in the first all-race elections in April 1994. He giggled with glee when he raised the hand of Mandela, the long-imprisoned leader of the African National Congress, and introduced “our brand-new president, out of the box” to crowds in Cape Town the following month.

Nobel Peace Prize laureate and retired Archbishop of Cape Town Desmond Tutu is being lauded around the world after his death Sunday at age 90.

Then, instead of leaving the limelight, Tutu became a moral guardian to what he proudly called the “rainbow people of God.” He didn’t shy from slamming the new government — or Mandela — when he felt it necessary.

Shortly after the 1994 elections, he publicly rebuked Mandela’s government for “having stopped the gravy train only long enough to get on.” The president complained, but soon announced salary cuts for himself, his cabinet and Parliament.

In the following years, one of Tutu’s greatest contributions was leading the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a statutory panel charged with investigating murder, torture, bombings and other crimes by Black and white people committed during apartheid, the former white minority rulers’ system of segregation.

As Tutu watched and often wept, perpetrators confessed to atrocities and victims forgave them in a wrenching process of national catharsis.

“To preside over an attempt at healing the nation, that is the most humbling honor of all,” Tutu told The Times in June 1997.

He also used his independent stature to lament the state of his country, speaking out against crime, corruption and the ANC’s failures on AIDS and poverty. He believed that many South Africans were too intimidated to speak out.

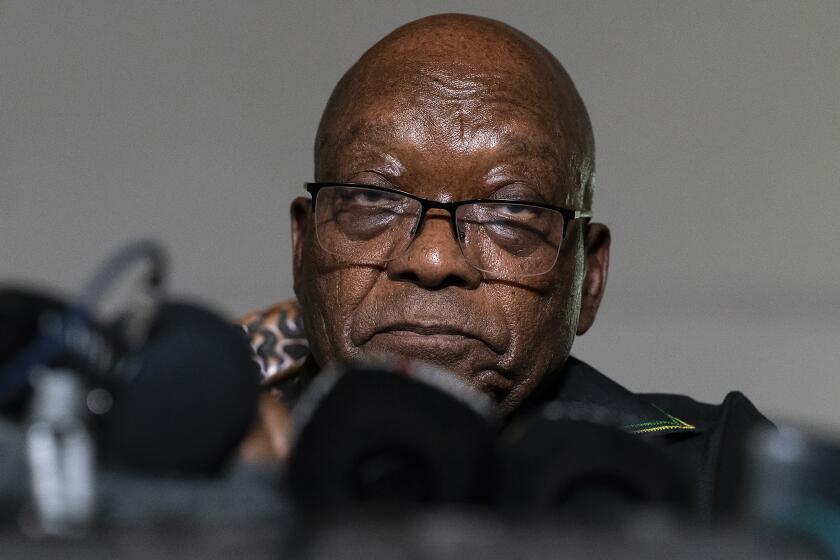

Weeks before the country’s 2009 election, he criticized the ANC, warning the party, “You are not God,” and complaining that he was not looking forward to seeing Jacob Zuma become president. Zuma was later elected but resigned in 2018 after an administration marked by repeated corruption scandals.

South Africa’s former leader turned himself over to police early Thursday to begin serving a 15-month prison term for contempt of court.

Tutu announced his retirement from public life in 2010. But he continued to speak out on social and political issues, offering support for same-sex marriage, assisted dying and human rights. In 2018, he condemned President Trump’s decision to formally recognize the divided city of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, saying “God is weeping.”

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born Oct. 7, 1931, in a dirt-poor Black township outside the conservative white town of Klerksdorp, about 100 miles southwest of Johannesburg. His family soon moved to Muncieville, near Johannesburg, where his late father, Zachariah, was headmaster of the segregated high school for Black students.

“One of the things I found difficult about him was he drank,” Tutu told a South African Broadcasting Corp. interviewer in 1997.

“He drank often. He was excessive. And then he would not be nice to my mother. Sometimes he beat my mother. He beat her up. And I really got very, very angry.”

His mother, Anetta, was an uneducated maid for a white family. Tutu recalled her as compassionate, gentle and caring, an abused woman who stood up for the underdog in any argument.

“Of all the people in the world, my mother was the greatest influence on me,” he said.

It is just after 9:30 a.m., and a throng of onlookers stands along Dr.

Tutu was a small, sickly child. He suffered polio as a boy, and it left his right hand shriveled and semi-paralyzed. As a teenager, he spent 20 months in the hospital for tuberculosis. He was so nearsighted that he was fired as a golf caddy when he kept losing track of the balls.

He wanted to be a doctor, and was one of a handful of Black students admitted to medical school. But his parents couldn’t afford the fees, so Tutu became an English teacher at his father’s school instead.

Tutu married a Muncieville woman, Leah Nomalizo Shenxani, in 1955. They were inseparable over the years and had four children. He is survived by her, their children and several grandchildren.

Tutu quit teaching because the government had imposed Bantu education, which was designed to train Black students only as laborers for white people.

“I felt I couldn’t be part of this,” he recalled.

He was ordained as a priest in 1961 after attending St. Peter’s Theological College in Rosettenville near Johannesburg. He later insisted, usually with a twinkle in his eye, that he joined the clergy because he didn’t know what else to do.

“It wasn’t highfalutin, noble ideas, like I wanted to serve God or serve our people,” he told SABC with a laugh. “Which shows that God can use even the worst kind of instrument for his works.”

But Tutu’s oratorical skills and powerful intellect were undeniable. In 1962, he won a scholarship to King’s College in London. After five years, he was named chaplain at South Africa’s University of Fort Hare. He soon returned to Britain with the World Council of Churches.

He came home for good in 1975, when he became the first Black Anglican dean of Johannesburg.

The then-unknown cleric emerged in the headlines in May 1976 when he wrote a public letter to the white prime minister, John Vorster. Tutu warned of his “growing nightmarish fear” that “bloodshed and violence are almost inevitable” if repression continued.

Vorster ignored the warning, and Tutu was vilified in the white-run media. A month later, riots exploded near Johannesburg in Soweto, the country’s largest Black township. It would take nearly 18 years and tens of thousands of deaths, but the Soweto uprising marked the beginning of the end of the apartheid era.

But that was hardly assured. With Mandela and most other Black leaders in prison, and the African National Congress and other liberation groups banned, Tutu became the most prominent, public voice in South Africa to rail against the racism and oppression of minority white rule.

His influence grew when he was elected the first Black general secretary of the South African Council of Churches in 1978.

Soon after, he launched a campaign urging the international community to bring pressure to bear on the apartheid regime by imposing punitive sanctions. Black people already were suffering, he said, in response to concerns that sanctions would hurt them as well.

“It is better to suffer with a purpose,” he explained.

In 1984, the same year he won the Nobel Prize, he was named the Anglican Bishop of Johannesburg. He became Archbishop of Cape Town, the head of the church nationwide, two years later.

Tutu and members of his family were repeatedly arrested and harassed. His passport was confiscated and police followed him, even as he jogged each morning.

“I like to be liked,” he told The Times. “It was very, very painful to be hated.... Why did they hate me? Because I was in their view Ogre No. 1, Public Enemy No. 1. Because I was regarded as Mr. Sanctions.”

Tutu justified his political activism by describing the Bible as the most subversive document in history, citing Moses’ leading of the Jewish slaves out of Egypt. He challenged the self-described Christian government over human rights abuses, and repeatedly broke the law by leading protests and boycotts.

“I’m not defying the government,” he once explained. “I’m obeying God.”

But Tutu angered some Black supporters when he also condemned township violence, especially mobs who killed suspected enemies by pinning them inside tires that were then set on fire, a gruesome practice known as necklacing. He was called a sellout, and worse.

When Mandela was released from 27 years of imprisonment in February 1990, he spent his first night of freedom at the archbishop’s residence in Cape Town. Tutu later repeatedly mediated as violence escalated before the 1994 elections.

Even in the darkest days, Tutu said he never lost hope — or faith.

“I never gave up,” he told The Times. “It was a matter of theology. Sometimes you wish you could whisper in God’s ear, ‘God, I know you’re there. But could you make it a little more obvious?’”

In his very active “retirement,” he led the Elders, a group of statesmen including Mandela and Jimmy Carter who used their influence to work behind the scenes for peace.

He campaigned against AIDS and cancer, and never shied from controversial subjects. In 2009, Tutu characteristically brushed off attacks over his view that four white students facing criminal charges over a racist video should instead be forgiven.

“I always have people criticizing me. That’s not new,” he said. “And I always end up being right.”

Drogin is a former Times staff writer. Former Times staff writer Robyn Dixon contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.