From the Archives: Nelson Mandela: Anti-apartheid icon reconciled a nation

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — Nelson Mandela, who emerged from more than a quarter of a century in prison to steer a troubled African nation to its first multiracial democracy, uniting the country by reaching out to fearful whites and becoming a revered symbol of racial reconciliation around the world, died Thursday. He was 95.

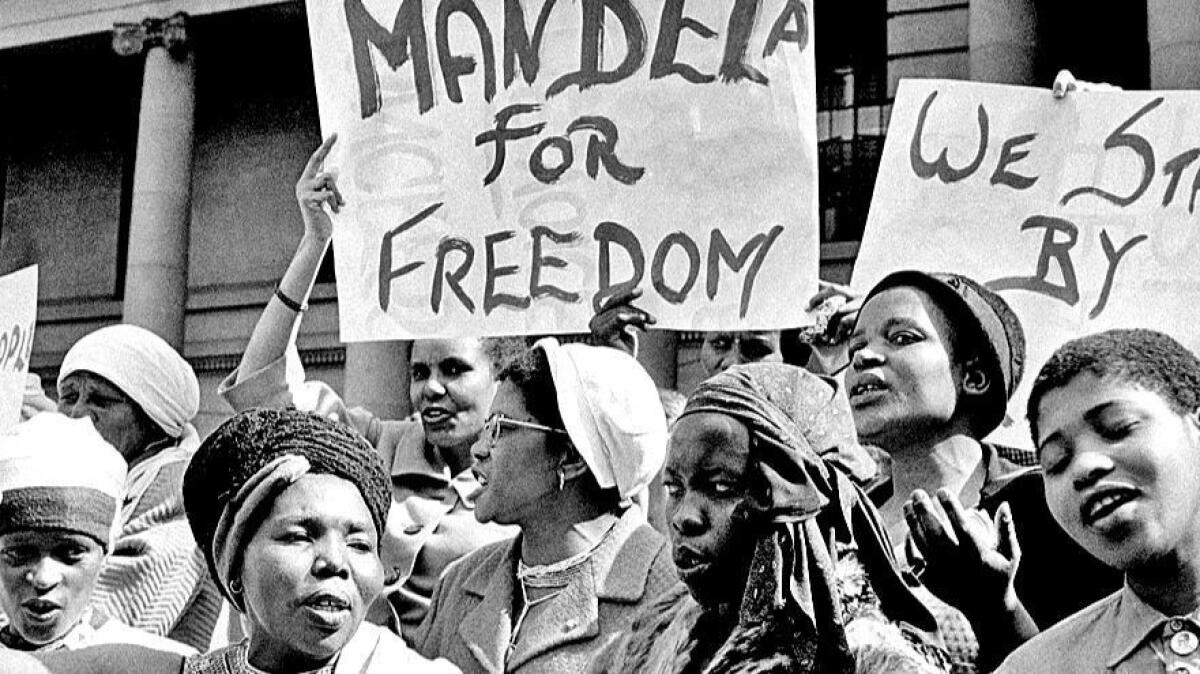

Long before his release from prison in 1990, at age 71, Mandela was an inspiration to millions of blacks seeking to end the oppression of more than four decades of apartheid, and his continued incarceration spawned international censure of South Africa’s white-minority government.

Successive white South African leaders had portrayed him as a dangerous terrorist. But when Mandela was freed, after 27 years, he surprised many by saying he bore no ill will toward his white Afrikaner jailers.

Preaching reconciliation, he guided the nation through four years of on-again, off-again constitutional talks, using his moral authority to address the demands of an impatient black majority while, at the same time, winning over suspicious whites.

Mandela and the man who released him, President Frederik W. de Klerk, shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. A year later, Mandela, the son of a tribal chief, succeeded De Klerk after a historic, peaceful election, the images of which were seared into the memory of a global audience: millions of blacks casting the first votes of their lifetimes.

Under Mandela the economy grew, a constitution guaranteeing equality and press freedom took root, and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission unearthed many dark secrets of apartheid and granted amnesty to both whites and blacks accused of political violence.

During his five-year term in office, Mandela’s formal dignity and his skill in building consensus made him a rarity on a continent plagued by corrupt dictators. Although his strongest supporters were deeply distrustful of whites, who controlled much of the country’s economy, Mandela made a determined -- and largely successful -- effort to ease white fears.

As his term drew to a close, he decided not to stand for reelection in 1999 and voluntarily stepped aside -- a move almost unheard of among African leaders. His party, the African National Congress, again won national elections and chose Mandela’s vice president, Thabo Mbeki, as his successor.

After leaving the government, Mandela’s worldwide stature continued to grow. He became active in the fight against AIDS; a son died of the disease in 2005. He also traveled widely in support of human rights and efforts to end poverty and spoke out vehemently against the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. In 2004, at age 85, Mandela announced his retirement from public life.

Mandela’s given name, Rolihlahla, means “tree shaker,” or “troublemaker,” in the Xhosa language. He was named Nelson by his teacher on the first day of school, but most South Africans, including those closest to him, called him simply Madiba, the name of his clan and a term of affection and respect.

Mandela, an intensely private person, sometimes chafed at the saint-like celebrity that cloaked him late in life.

“In real life we deal not with gods, but with ordinary humans like ourselves: men and women who are full of contradictions, who are stable and fickle, strong and weak, famous and infamous,” he wrote in a letter to his then-wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, from prison in 1979.

As a leader of the African National Congress, or ANC, Mandela was at the forefront of the struggle against apartheid, which used state violence and repressive laws to segregate and oppress South Africa’s black majority.

Blacks and “Colored,” or mixed race, people were forced to live in restricted areas and could not move freely without passes. Black mini-nations, known as “homelands” or “bantustans,” were set up in rural areas with few natural resources or amenities. Blacks got a separate, limited education, with a restricted number of places in black universities.

More than 20,000 people died in civil and political strife under apartheid, and thousands more were jailed or tortured. In the years after Mandela was banished to Robben Island, a penal colony in frigid waters off the coast of Cape Town, the nation faced anarchy, while international economic and cultural sanctions made Africa’s richest and most powerful country a global pariah.

In 1985, Mandela wrote to the National Party government from prison, seeking talks on a negotiated settlement to the crisis. Then-President Pieter W. Botha offered to free Mandela if the ANC agreed to lay down its arms. Mandela replied in a message to his daughter, Zindzi, who read it to a crowd gathered in the black township of Soweto.

“I cherish my own freedom dearly, but I care even more for your freedom,” read Mandela’s message, the first words from him after more than 20 years in prison. “I am not less life-loving than you are. But I cannot sell my birthright nor am I prepared to sell the birthright of the people to be free.

“Only free men can negotiate,” he said. “Your freedom and mine cannot be separated.”

In 1988, Mandela turned 70 and, a month later, contracted tuberculosis. His illness was successfully treated, but government officials worried they were being held hostage by Mandela’s imprisonment. Releasing him could spark a revolution, but his death in prison might do the same.

The government launched an elaborate plan to demythologize Mandela and “release him in steps,” as one official put it at the time. That year, he was transferred from his prison in suburban Cape Town to a nearby prison farm, where he lived in a three-bedroom house.

Mandela met secretly at the prison, and even in the presidential mansion, with Botha and government ministers to draw up a framework for discussions between the government and the ANC. Botha suffered a stroke in 1989 and De Klerk took over soon after, freeing seven of the longest-serving political prisoners. Four months later, in February 1990, De Klerk lifted the ban on the ANC and other black political groups and freed Mandela.

The first years after Mandela’s release were rocky. About 10,000 people were killed from 1990 through ‘93, many of them in violence between competing black political forces, notably the ANC and the Inkatha Freedom Party.

Mandela suspected that much of the internecine bloodshed was fomented by white extremists, some operating from inside the government. Infuriated by the government’s reluctance to investigate the killings, Mandela walked out of peace talks in 1992. He returned to the negotiating table several months later.

In April 1994, South Africa staged its first democratic elections and the ANC swept to power in the new multiracial Parliament, which elected Mandela the nation’s first black president. He was 75 years old.

As president, Mandela brought together right-wing whites and militant blacks under his banner of nonracial democracy. He won broad support for an ambitious program of reconstruction and development. Unemployment, crime and racial conflict persisted, but the president’s popularity helped keep the country together.

Mandela’s personal life, though, had begun to fall apart after his release from prison. His commitment to a unified South Africa put him at odds with Madikizela-Mandela, the second wife who had stood beside him throughout his incarceration but became increasingly radicalized. They separated in 1992 after she was convicted of orchestrating the kidnapping and assault of several township youths, one of whom was killed, by her bodyguard retinue.

Then, as president, Mandela forced his estranged wife’s resignation as deputy minister of arts, culture, science and technology after she was embroiled in a series of shady business deals and other scandals. He finally sued for divorce, but she refused to settle out of court.

In March 1996, the president took the stand in a packed Johannesburg courtroom to publicly accuse her of adultery with an ANC aide. Speaking stiffly, Mandela said that after his release from prison, his wife had never entered their bedroom while he was awake.

“I was the loneliest man during the period I stayed with her,” he said. The judge granted the divorce and longtime friends, such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu, lamented the demise of the relationship.

“We wanted them to have a kind of fairy-tale ending,” Tutu said.

Two years later, on his 80th birthday, Mandela married Graca Machel, the former first lady of Mozambique whose husband had died in a plane crash.

“I don’t regret the ... setbacks I’ve had because, late in my life, I am blooming like a flower because of the love and support she has given me,” Mandela said of Machel. “She has changed my life.”

An absent father and husband most of his life, Mandela had as many as four grandchildren living with him during his final years as president. Besides Machel, he is survived by a daughter, Maki, from his first marriage; two daughters from his marriage to Madikizela-Mandela, Zindzi and Zenani; and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Nelson Mandela was born July 18, 1918, in Mvezo, a hamlet in South Africa’s Transkei region, now the Eastern Cape. His father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, a nobleman and chief in the small Thembu tribe, named him Rolihlahla.

“I do not believe that names are destiny or that my father somehow divined my future,” Mandela wrote in his 1994 autobiography, “Long Walk to Freedom,” “but in later years, friends and relatives would ascribe to my birth name the many storms I have both caused and weathered.”

Polygamy was a tribal custom, and his father kept four wives and had 13 children.

Mandela’s father was a stern, stubborn man with a strong sense of justice. Shortly after Mandela was born, his father refused to acknowledge the authority of a white magistrate. The official accused him of insubordination and took away his cattle, land and tribal chieftaincy.

Mandela’s mother, Nosekeni Fanny, was forced to move her children to nearby Qunu. Her new kraal -- a homestead surrounded by a ring of branches -- had three mud-walled huts, one each for cooking, sleeping and storage. The family slept on mats on the ground, grew their own food and wore only blankets.

By the time he was 5, Mandela had been sent to watch cattle and sheep on the rolling green hills. He was surrounded by family, was steeped in tribal custom and lore and developed a love of the outdoors. He recalled a happy, carefree childhood.

Unlike his father -- a traditional healer who never learned to read or write -- Mandela was baptized into the Methodist Church and at age 7 was sent to a one-room school. Mandela left his mother’s side at 9, after his father died. The acting Thembu tribal regent had become his guardian, and Mandela moved to his far grander kraal.

At the tribal court, he learned a lesson that would be fundamental to his own leadership. A ruler, the regent told him, should be like a shepherd: “He stays behind the flock, letting the most nimble go on ahead, whereupon the others follow, not realizing that all along they are being directed from behind.”

Like his father, Mandela was groomed to counsel the Thembu king. He was sent to local English missionary schools and the University College of Fort Hare, then the only center of higher education for blacks.

“I was 21, and I could not imagine anyone at Fort Hare smarter than I,” he recalled.

He soon quit the student council to protest a minor point of school policy. He then defied the headmaster’s order to rejoin and was expelled. Like his father, Mandela refused to back down on a matter of principle.

Disgrace was followed by shock. Back home, the regent had arranged for him to marry a local girl. Mandela stole some oxen to sell for traveling money and ran away to the so-called city of gold: Johannesburg.

It was 1941, and the former mining town was emerging as a modern city. Mandela was shortly introduced to Walter Sisulu, a local black leader and businessman.

The meeting changed their lives, and South Africa’s future.

Sisulu arranged for Mandela to complete his college degree and to clerk at a white law firm. Soon after, Mandela enrolled in the law school at the University of the Witwatersrand. He was the only black law student in the class of 1946. He would complete his law degree from a correspondence college while in prison.

Sisulu, a member of the ANC, helped channel Mandela’s anger. Mandela joined the organization and, while living at Sisulu’s home, met and married his mentor’s niece, Evelyn Ntoko Mase. The couple had four children before separating in 1955 and divorced three years later.

Mandela wrote later that he was unable to pinpoint “when I knew that I would spend my life in the liberation struggle.” But he knew why: “A thousand slights, a thousand indignities,” he said, had produced “an anger, a rebelliousness, a desire to fight the system that imprisoned my people.”

The first white settlers, known as Afrikaners, had brought racial segregation to South Africa in the 17th century, and British colonial rule did little to ease the oppression. Blacks were deprived of their farmland, herded into urban slums and denied the vote and other basic rights.

A whites-only election in 1948 brought to power an Afrikaner government determined to entrench white rule through a legal system that mandated racial discrimination in jobs, housing and virtually every other aspect of life. The new National Party government called it apartheid, an Afrikaans word meaning “apartness.”

Blacks, Indians and Colored people were treated, by law, as inferior to whites. Blacks, though outnumbering whites 4 to 1, were at the bottom of the racial hierarchy.

Under apartheid, white officials could seize any property they wanted. Ultimately, millions of nonwhites were forced from their homes at gunpoint and dispatched to urban “townships,” which the government regarded as temporary worker camps, or to the barren rural bantustans.

Mandela, Sisulu and others in the new ANC Youth League called for a campaign of strikes, boycotts and civil disobedience. But that meant defying not only the government but an older generation of ANC leaders who wanted to fight within the law. When the dust cleared in the ANC, Mandela was among its new leaders.

In 1952, Mandela and Oliver Tambo, who later became president of the ANC, opened the country’s first black law firm. Together, they tried using the courts to fight the countless indignities of a regime that classified people literally by the curliness of their hair or the size of their lips.

Mandela became increasingly overt in opposing the government’s racial policies. The result was a series of arrests and legal bans that prevented him from addressing public gatherings or traveling outside Johannesburg.

In 1956, he and 155 other people, ANC leaders and their allies, were arrested in a nationwide crackdown and charged with trying to overthrow the state and impose communism. Their treason trial lasted four years, but all were acquitted after Mandela convinced the court that nonviolence was a core principle of his organization.

By then, South Africa was in turmoil. In March 1960, police had massacred 69 unarmed black protesters and wounded about 190 others in Sharpeville, a squalid township south of Johannesburg. The government responded to the resulting outcry by banning the ANC, the Communist Party and scores of other political groups as terrorist threats. Martial law was declared.

Changing tack again, Mandela convinced the ANC’s underground leadership that violence had become inevitable and necessary. He was authorized to create a secret military force, a repudiation of the organization’s 50-year policy of nonviolence.

“For me, nonviolence was not a moral principle but a strategy; there is no moral goodness in using an ineffective weapon,” he explained in his autobiography.

His army, called Umkhonto we Sizwe, or Spear of the Nation, launched a campaign to sabotage government installations, hoping to disrupt the economy and frighten away investment without causing a loss of life. Even though the ANC army would much later step up its guerrilla war, it never posed a serious threat to the apartheid government.

Mandela had remarried in 1958, to Nomzamo Winnifred Madikizela, better known as Winnie, and they had two daughters. “Her spirit, her passion, her youth, her courage, her willfulness -- I felt all of these things the moment I first saw her,” he wrote.

But they saw little of each other. To avoid arrest, he moved constantly, traveling by night, sleeping by day. He let his hair grow, shed his lawyer’s suits for farmer’s overalls and posed as a gardener.

Slipping across the border, he arranged military training for ANC members in other African countries. His secret return to South Africa and daredevil underground existence earned him the title of the “Black Pimpernel,” polishing his romantic image among blacks.

After his arrest in August 1962, Mandela was sentenced to five years in prison for incitement to violence and leaving the country illegally. While serving that term, he and the ANC’s military high command were brought back to court on a charge of treason, and were eventually convicted of sabotage.

The eloquence of his speech at that trial, in 1964, echoed long after he, Sisulu and other ANC leaders were locked away and silenced.

“I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities,” Mandela told the hushed courtroom. “It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

In a ruling that would change the course of South African history, Mandela and his codefendants were not sentenced to death, as had been expected. The judge, in giving them a life sentence, said, “It is the only leniency which I can show.”

They were sent to Robben Island, a harsh penal colony off Cape Town.

“I could walk the length of my cell in three paces,” Mandela later wrote. “When I lay down, I could feel the wall with my feet and my head grazed the concrete at the other side.... I was 46 years old, a political prisoner with a life sentence, and that small cramped space was to be my home for I knew not how long.”

For 13 years, Mandela labored in the limestone quarry, breaking rocks into gravel. He could see only one visitor, and write and receive one heavily censored letter, every six months. Newspapers, radios and clocks were banned.

Working in the quarry damaged his eyes, and later in life photographers were asked never to use flashes when photographing him.

His health deteriorated. In 1984 he was found to have cysts on his liver and a kidney. Four years later, he contracted tuberculosis.

But Mandela said he never surrendered to despair.

“I do not know that I could have done it had I been alone,” he wrote. “But the authorities’ greatest mistake was to keep us together, for together our determination was reinforced.”

The political prisoners fought for better food, equal clothing and study facilities. Mandela was their spokesman, lawyer and teacher. Robben Island became known as Mandela University, a worldwide symbol of apartheid’s repression but also a school for imprisoned activists.

Mandela was moved to slightly more comfortable quarters at Pollsmoor Prison in suburban Cape Town in 1982. For the first time in 20 years, he was allowed to see and touch his wife and daughters.

From his new cell, and later from a small cottage at Victor Verster Prison, about 35 miles from Cape Town, Mandela initiated negotiations with the white leadership. Because he knew his lifelong ANC colleagues wouldn’t approve, he didn’t tell them.

It wasn’t until February 1990 that De Klerk legalized the ANC and other long-demonized liberation groups, released all political prisoners and began dismantling apartheid. Mandela was among the last to be set free, refusing to renounce violence as the white government had insisted and agreeing only to unconditional release.

Hundreds of reporters jammed the prison gates on the day of his release. He was a thin, graying 71-year-old and he recoiled when a TV crew pointed a boom microphone at him, fearing it was a weapon.

The next four years tested Mandela’s political skills. He was challenged by rivals and doubters in the ANC and other anti-apartheid groups, as well as by hard-liners in De Klerk’s government. Multiparty talks to draft a constitution and prepare for elections foundered again and again.

Police violence and township massacres escalated sharply, partly because government security forces had secretly armed and trained Zulu warriors from the Inkatha Freedom Party.

The assassination of black Communist Party leader Chris Hani in April 1993 was a turning point. The country appeared on the edge of race war when Mandela appeared on national television to plead for peace.

“Now is the time for all South Africans to stand together against those who, from any quarter, wish to destroy what Chris Hani gave his life for -- the freedom of all of us,” he said.

The transition to majority rule had begun.

The election the following April was a joyous event. The ANC won a sweeping victory and Mandela was inaugurated in Pretoria as the first president of a new South Africa.

The challenges were immense, and the performance of Mandela’s inexperienced Cabinet, particularly in key areas such as education and health, was sometimes disappointing.

Mandela’s government largely failed to meet its campaign promise to improve healthcare and education and to visibly change the lives of the poor. Many blacks complained that he was too conciliatory toward whites, and many whites chafed at his black economic empowerment initiatives.

But South Africa’s democracy brought a multiracial Parliament, an independent judiciary, a free press and integrated schools. A new constitution guaranteed long-denied rights and freedoms. And the country finally was at peace.

South Africa’s grand experiment, for all its shortcomings, was working.

Mandela refused to take credit.

The final paragraphs in his 2010 book, “Conversations with Myself,” reflected that humility:

“One issue that deeply worried me in prison was the false image that I unwittingly projected to the outside world; of being regarded as a saint,” he said.

“I never was one, even on the basis of an earthly definition of a saint as a sinner who keeps on trying.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.