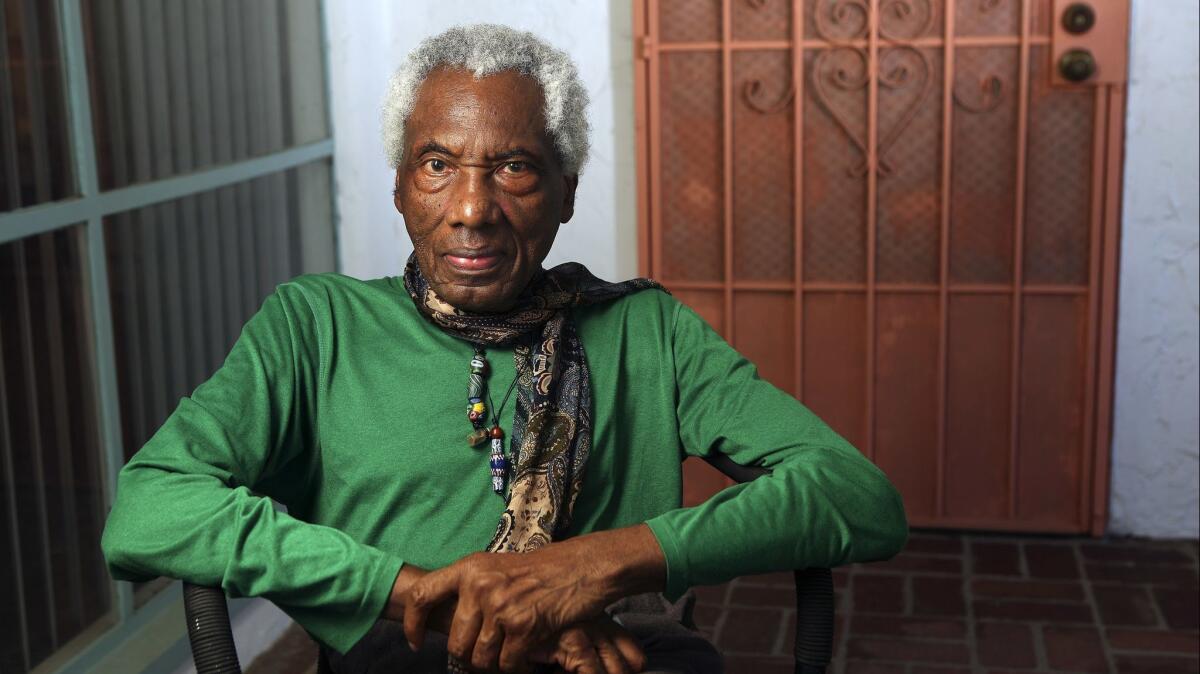

John Outterbridge, a Central L.A. assemblage artist and educator, dies at 87

John Outterbridge, a central figure in the Black assemblage arts movement and former director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, has died in Los Angeles. He was 87.

Outterbridge died of natural causes, said his daughter Tami, who was at his side.

The artist was known for his evocative sculptures made from found or discarded materials including cloth, containers and metal. Some of his most celebrated work includes a series of doll figures, stitched from rags, hair and wood scraps, that reference the black tradition, community and folklore.

Growing up in North Carolina, John Outterbridge spent hours watching his white-haired grandmother, bent over on hands and knees, scrubbing floors.

Born March 12,1933, in Depression-era Greenville, N.C., Outterbridge grew up surrounded by creativity. His mother wrote poetry and played piano; his uncles and cousins were musicians. Outterbridge came to know assemblage through his handyman father, an avid salvager who filled his family’s backyard with items from the junk trade.

“Castoffs, what was junk to others, became resource, conversion, meaningful substance,” Outterbridge recalled in a 2015 interview with The Times. “Images of that backyard museum still dance in my head. They play out in my thoughts and in my work.”

After attending an agricultural and technical college in Greensboro, N.C., to study engineering, Outterbridge enrolled in the Army and served in Germany during the Korean War. He became something of a military artist, painting murals in American high schools in Germany and officers’ clubs.

When his service ended, he enrolled in the American Academy of Art in Chicago while working as a bus driver on the side. It was there that he became fascinated with fabric scraps and rags, one of his trademark materials.

“I’d always see the ragmen, who collected rags for a living,” he said in a 1992 interview with The Times. “They’d go around, calling up to people in apartment buildings for rags, and they could send their kids to college on what they made. Rags became something I always wanted to use.”

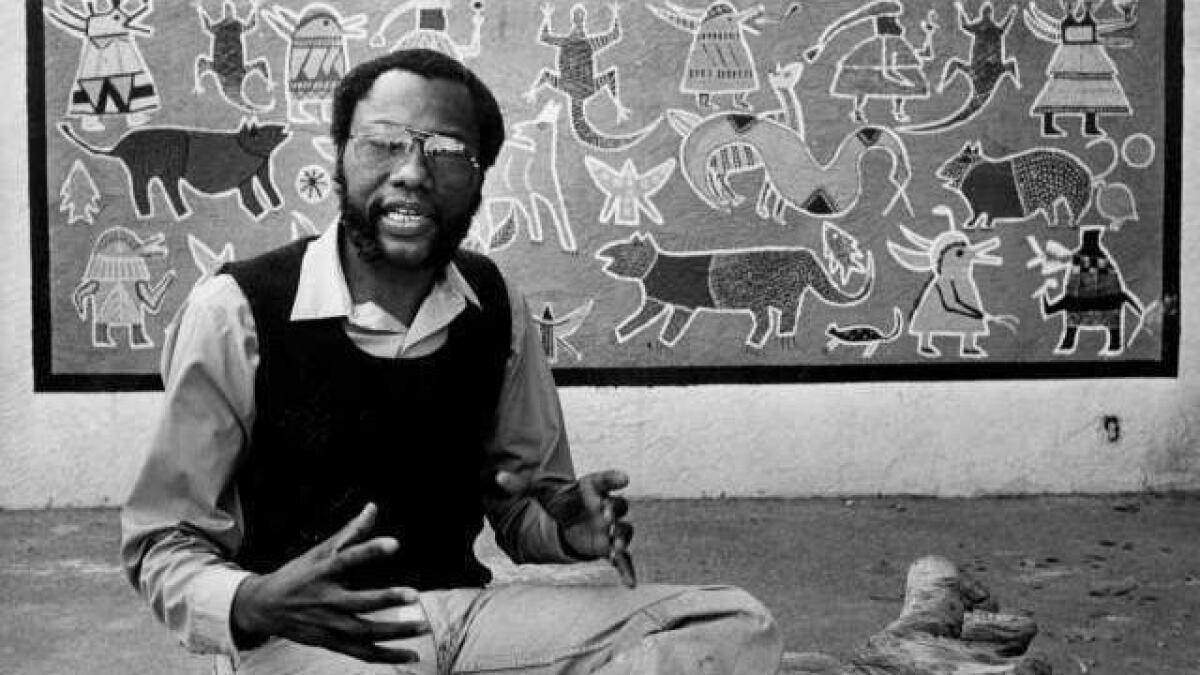

In 1963, two years before the Watts riots, Outterbridge moved to L.A. He befriended artist Noah Purifoy, co-founder of the Watts Towers Arts Center and father of the Black assemblage movement.

In the 1960s and 1970s, assemblage — the practice of creating artwork from discarded items — gave Black L.A. artists the chance to reclaim their community while calling out the indignities they faced. Outterbridge and other artists including Betye Saar and Melvin Edwards were central figures in the movement who found inspiration for their work from the 1965 Watts riots.

One such work is his 1969 “Containment Series,” a collection of rectangular pieces made of tin cans, rusted nails and other cast-off materials exploring the concept of constraint. Another work, “About Martin,” which features a teeny suit jacket and a laundry receipt made out to Martin Luther King Jr. inside a wood cabinet, is Outterbridge’s 1975 homage to the civil rights leader.

Although he was a gifted artist, much of Outterbridge’s career was dedicated to arts administration, education and activism.

He was a founding director of the Communicative Arts Academy in Compton from 1969 to 1975. In a 2016 interview with KCET, Outterbridge described the academy as a gathering spot for the community. “It was a bright, colorful place that we raised up on the other side of the train tracks and where we raised the roof with songs and plays and music and movements that didn’t happen anywhere else in the city,” he said.

In 1975, Outterbridge became director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, a community facility next to Simon Rodia’s landmark spires in South-Central L.A. After nearly 17 years, he retired from the position in 1992 to dedicate more time to his art practice.

Two years later, Outterbridge represented the U.S. along with Saar in the 22nd Brazil Bienal, a biannual exhibition that featured work by 206 artists from 71 countries.

He continued to create through his later years, producing work including 2002’s “Remnants of an Apron Lost,” which transformed a wooden paddle into an African-inspired fetish figure, and 2009’s “Hooked,” a claw made from bits of wood.

But it was only in the past decade that Outterbridge received widespread recognition for his work, with his pieces shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Venice Biennale.

His work was featured in several of the 2011 Pacific Standard Time exhibitions. His 2011 show “The Rag Factory” at LAXART in 2011 marked his first solo exhibition in Los Angeles since 1996. And in 2012, the California African American Museum honored Outterbridge with a lifetime achievement award alongside actor and director Sidney Poitier.

Outterbridge’s art is in the collections of museums including the California African American Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.