L.A. artists discuss ‘What LACMA means to me’

For more than 50 years the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has captured the imaginations of some of L.A.'s most beloved artists, often speaking to the vibrant complexity of the city they call home. It has also provided fertile ground for grand daydreams and fodder for lifelong inspiration.

A handful of them share what it has meant to them, in written comments and interviews.

FULL COVERAGE: LACMA at 50

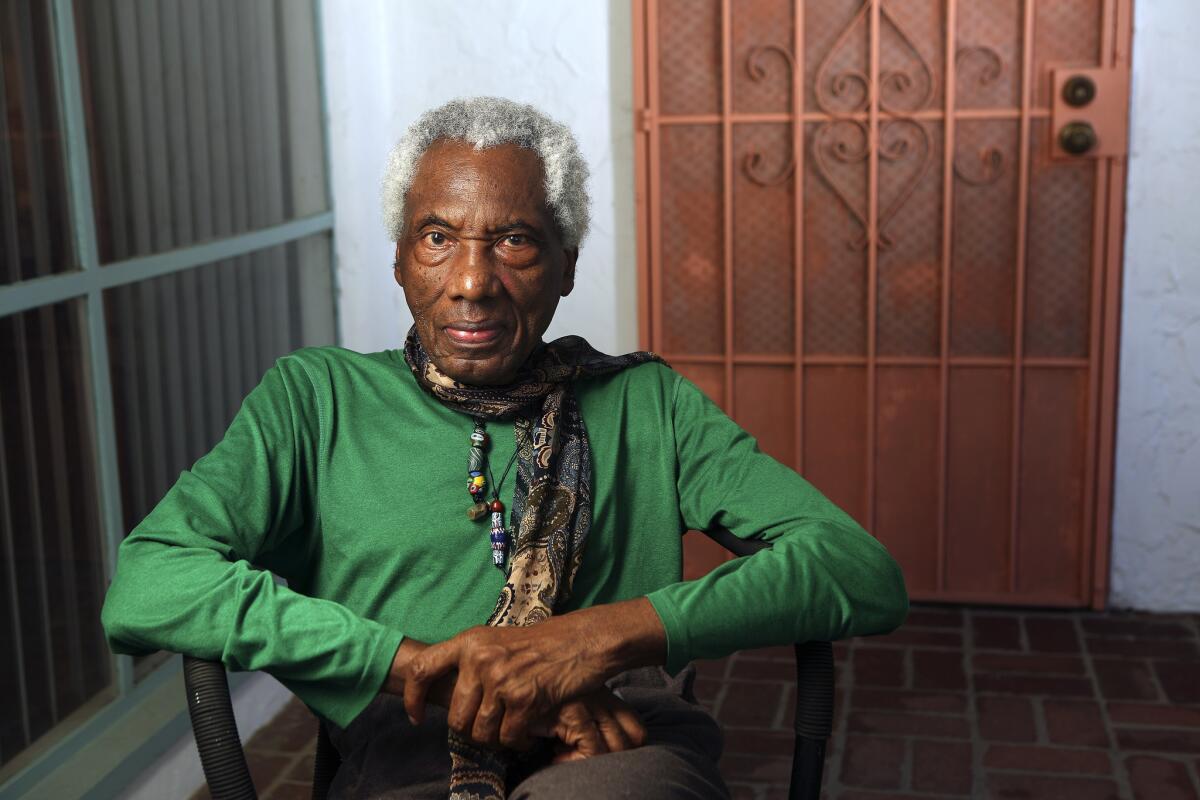

ALTADENA, CA-MARCH 27, 2015: Artist John Outterbridge is photographed at his home in Altadena on March 27, 2015. He is one of six Los Angeles artists discussing their memories of the

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

John Outterbridge (with daughter Tami Outterbridge) on his childhood in Greenville, N.C., and a tribute piece to his parents that is part of LACMA's permanent collection titled "John Ivery's Truck: Hauling Away the Traps and Saving the Yams":

Many would have called my father a handyman, a jack-of-all-trades, a junkman. I'll call him a "collector." He collected the things of life and its experiences, and his truck was that receptacle. "John Ivery's Truck" is a genuine characterization of what builds an individual and the idea that life itself is a chunk of raw "poetic-ness" that's constantly in the process of being molded, shaped, purified. It's about my father and how unique, how tough, how courageous, how consistent he was. How complete he ended up being in spite of his circumstances.

My father oiled that old truck, and he kept it running; he kept it humming. But more than that he oiled and anointed the individuals who came into contact with him — like me and my brothers and sisters and even my mother, Olivia, who shared his courage and so much of what he represented. He was a man who — when my mother could no longer stand or speak — came home each night and got down on his knees to whisper prayers in her ear. How do you kneel on 70-year-old knees? That's character.

"Hauling away the traps" speaks to the challenges that we live with and yet we find a way to shoulder them. It's about the colorful baggage and burdens we carry and how the heart is that carrier. "Saving the yams" says that no matter what my circumstances, I will always find an opportunity to share the "poetic-ness" of life. Like yams, life is a tasty edible thing that we can devour.

That piece is more than a hunk of wood. It's also the carriage of my first museum experience because, as a kid, we never had a museum. But we did have a backyard that was arrayed with the precious baubles of the so-called junk trade. It was fragrant with the sweet smells of the lemongrass and red clay that my siblings and I ate. It was decorated with glass bottles and colorful rags, with rusty old machines and the wooden Coca-Cola crates that we sat on with our too-short legs as we learned to shift gears in "John Ivery's Truck." Our yard was alive with inanimate objects — and living things too — like the goat my father brought home because that's how someone had seen fit to pay him that day. Castoffs, what was junk to others, became resource, conversion, meaningful substance.

Images of that backyard museum still dance in my head. They play out in my thoughts and in my work. The idea that life — that art — has the audacity to be anything that it needs to be at a given time. And now a piece of that, a piece of John Ivery and Olivia, lives because my daddy's truck roared right into LACMA and parked itself!

VENICE, CA-MARCH 27, 2015: Artist Ed Moses is photographed in front of acrylic on canvas crackle paintings at his studio in Venice on March 27, 2015. Moses is one of six Los Angeles artists discussing their memories of the

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Ed Moses on young love and paintings made of red:

I loved the dioramas, I was in love with this girl, she was really cute, and I had a pair of white buck shoes for my trip to Hawaii, so I walked around the rail. And I wore them on the field trip and everyone commented on my shoes, and suddenly Neva Jean Carpenter noticed me, who I'd always had a crush on.

This was in 1939 — my first memory of a trip to Exposition Park. I saw giant dinosaur skeletons. Expo Park had historical paintings as well as dioramas before the Wilshire building.

I remember a couple of Picassos captured my attention along with various Renaissance painters.

The biggest challenge I faced at LACMA was 26 years later staging "The Red Paintings." That show was curated by Stephanie Barron under Maurice Tuchman's direction. "The Red Paintings" were coincidentally installed as my graduate thesis exhibition at UCLA. Prior to that there were annual events and the invitational at Exposition Park, which was the first time my work was exhibited at LACMA. Billy Al [Bengston] was in that invitational, too. Both of us were feeling mighty fine since that was the only game in town for painters like us.

The Ed Kienholz show [in 1966] was, of course, great — especially "Back Seat Dodge." He insisted that they would charge and he would split the fee; everybody was outraged at his audacity. People lined up for two blocks to see that exhibition.

LOS ANGELES, CA – MARCH 26, 2015 -- Video and photography artist Judy Fiskin in her home studio,has asked that her face not be photographed. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

(Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Judy Fiskin on a mother's love and art for children:

I have a memory of going to LACMA as a young teenager with my mother when it was in Exposition Park. I remember it being in the basement, and I have a persistent but fuzzy memory of seeing a Van Gogh show there. This would have been around 1950, and I haven't been able to verify whether there actually was a Van Gogh show there around that time. [The show was from December 1958 to Jan. 18, 1959.] My mother was an art history major in college, and she went to whatever art there was to see in Los Angeles in those days and often took me with her. After my brother and I left for college, she was a docent at LACMA for 17 years.

In 2001 when I staged a video installation at LACMA called "What We Think About When We Think About Ships," I didn't think I could make art that children would relate to. But I came into my installation one day and there were three little boys inside, each with their eyes up against one of the peepholes, looking at the video screens, reciting the action in a way that told me that this was not their first viewing, cracking each other up and then starting over again when the film cycled back to the beginning.

Another time I came in and a little girl was twirling in front of LACMA's Fitz-Hugh Lane painting of a sailing ship, with her skirt billowing up around her. I felt those were among the best responses I'd ever gotten for my work — just expressions of unmeditated pleasure, unlike any reaction you'd get from an adult. Also, just before I was asked to be in the show, someone had told me that as a child they had made drawings in the street with glue and then set the glue on fire. I thought about this for days, feeling miffed that I had missed that as a child. When I started thinking about ways to represent ships, I realized that I could make a drawing of a boat in glue and light that on fire, and put it in the piece, and that was really satisfying.

LACMA used to have an art rental gallery. People could come in and rent a piece of art for a certain number of weeks at very low cost. The work of "emerging artists" was chosen for this program, and when my work was picked I felt I was on my way as an artist, even though no one rented my photograph.

LOS ANGELES - CA - MARCH 25, 2015 - L.A.-based Chicana artist Patssi Valdez in her studio in the Echo Park area of Los Angeles, CA, March 25, 2015. (Ricardo DeAratanha/Los Angeles Times)

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Patssi Valdez on youthful striving and a trip to Oz:

I saw a David Hockney exhibit at LACMA in the late '80s. I had been struggling as a painter, and one of my weakest points was color theory. Anyway, I attended this show with a friend and I said, "Oh, my God, I think I could do something like this," and this friend of mine thought it was the funniest thing she had ever heard. In a way it felt like a dare. I proceeded to make my first successful body of paintings after seeing that exhibit and that sort of launched my painting career.

Before that I was in Asco [a Chicano artist collective based in East L.A.] and a Chicano art group that was older than us was having a show at LACMA. We were 10 years younger and we were [upset]. We were like, "How about us?" I remember crashing that opening. I can't remember what I wore, but we showed up in these extreme costumes because we thought we should have been included.

As a very young artist I used to feel a lot of angst and I was very rebellious. I remember thinking, "How in the world am I going to get inside of this institution? When is the door going to open for an artist like myself?"

It almost felt like an impossibility, but I was determined that I was going to get in there somehow. That happened 40 years later. At one point I even forgot about it — I went about my career and didn't think about it. When I was finally approached to exhibit there I took it with a grain of salt. That was the Asco exhibit in 2011.

As an individual artist I'm still waiting. Well, I don't think I'm really waiting, but I'm hoping that one day I'll be accepted inside those doors with my own work, and I'm hoping that will happen in this lifetime. It's a county facility so I'm thinking the collection should be more diverse. I was disappointed that after the Asco exhibit they didn't purchase or collect one of the pieces from that show.

It was the only museum we had way back when, and it was extremely special as far as I was concerned — it was like reaching Oz. So I guess I'm still on the yellow brick road.

VENICE, CA - MARCH 27, 2015 -- Collage artist Alexis Smith is surrounded by her work and supplies used for creating new pieces in her studio in Venice on March 27, 2015. (Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Alexis Smith on the museum's evolution:

I was part of the group that started MOCA, and when we began that initiative LACMA was the only art museum in Los Angeles. Now that we have so many high-profile museums, it's hard to imagine what it was like when LACMA was the only game in town. It was important to establish MOCA as a voice for contemporary art in Los Angeles, but since then, LACMA has evolved more and more to incorporate contemporary art into the program. LACMA is a primary museum for Los Angeles with its broad program of art from around the globe and through the ages. Michael Govan's initiative to develop the campus and add major outdoor works has given it even more visibility as a thriving place for art in Los Angeles.

LACMA has several of my works in its permanent collection representing different media and different periods of time. A few years ago, LACMA selected my piece "Sea of Tranquillity" (1972) to print as a postcard. The funds for the acquisition were put together by a small group of local art collectors who purchased the work for LACMA. It means a lot to me that these friends came together to support my work and that LACMA selected this piece for a card that is still in print to benefit the museum.

LOS ANGELES, CA - April 7, 2015 -- Los Angeles artist ED Ruscha is photographed at his west L.A. library. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

(Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Ed Ruscha on a day to remember:

The 1965 LACMA opening gave the city a star-spangled jolt, and no one had any idea where it would lead us, which made everyone into idealists.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.