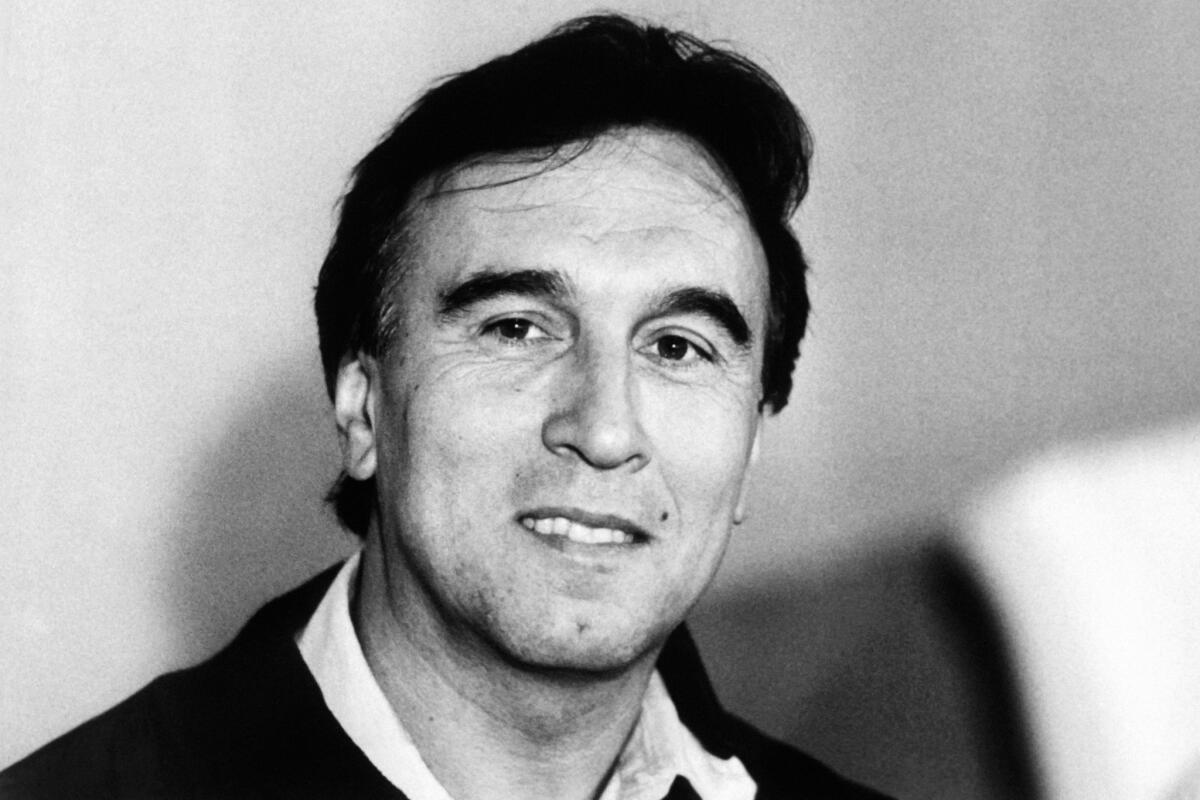

Claudio Abbado dies at 80; Italian conductor with wide-ranging mastery

Notable deaths of 2013

Claudio Abbado, an Italian conductor whose wide-ranging mastery of symphonic and operatic repertory and attention to detail drew comparisons to more famous maestros Carlo Mario Giulini, Arturo Toscanini and Herbert von Karajan, has died. He was 80.

A former music director of the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, the London Philharmonic, the Vienna State Opera and the Berlin Philharmonic, Abbado died Monday at his home in Bologna, the mayor’s office announced.

The cause was not given, but Abbado underwent surgery for stomach cancer in 2000.

One of his last notable concerts was leading Mahler’s Third Symphony — at 13/4 hours, the longest in the standard repertory — with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra at the Royal Albert Hall in London in 2007.

“Everything he did in this extraordinary performance was directed at sustaining an ensemble in which everyone listens intently to what all their colleagues are doing and responds instinctively,” reviewer Andrew Clements wrote of the concert in England’s Guardian newspaper. “The result was totally coherent and miraculously transparent. ... No one who heard this performance is likely to forget it; Abbado’s Mahler, like Furtwängler’s Wagner and Klemperer’s Beethoven in previous generations, is just peerless.”

Abbado last appeared in the Southland in 2001, when he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in two concerts primarily of Beethoven symphonies at the Orange County Performing Arts Center.

“Abbado has given the players a sense of freedom and individuality, without lessening the phenomenal ensemble playing that is Berlin’s hallmark,” wrote Times music critic Mark Swed.

Abbado achieved that combination through a lifelong devotion to meticulous preparation in rehearsal in order to achieve intense spontaneity in performance.

“I kept wondering when the blinding light of inspiration was about to hit us,” a former concertmaster with the London Symphony said in 1987, speaking about Abbado’s rehearsals.

“It never did. He has a highly analytical, careful approach, leaving nothing to chance. But in concert, the man seems to throw his reserve aside and go 150% all out for the music. It is electrifying. He can conserve everything until that moment. It is as though after the cerebral approach to making music in rehearsal, he allows himself the luxury of turning the emotional tap on.”

Abbado was born June 26, 1933, into a musical Milanese family. His father was a professional violinist. His mother was a pianist. His brother was a pianist and composer who eventually became director of the Milan Conservatory. His sister studied violin.

A visit to La Scala when he was 8 determined his future goal. “One day,” he wrote in his diary after the performance, “I will conduct.”

But first he threw himself into study of the piano and soon was accompanying his father in piano-violin duets. For a while, he was torn between piano, which he studied at the Milan Conservatory until 1955, and conducting, which he studied under Hans Swarowsky at the Vienna Academy of Music after graduating from the conservatory. Conducting won out.

A classmate and friend in Vienna was Zubin Mehta, future music director of the Los Angeles and New York philharmonics. In order to study the work of conductors in rehearsals, which were closed to students and the public, the two auditioned for the Musikverein Chorus. Once accepted in the bass section of the chorus, they scrutinized conductors such as Karajan and Bruno Walter.

After graduating, the two went to the Tanglewood Festival near Boston, where Abbado beat out Mehta to win the Serge Koussevitsky Prize for conducting in 1958. The award came with an offer to take over an American orchestra, but Abbado turned it down to return to Europe for further studies.

In 1963, he shared the prestigious Dimitri Mitropoulos prize for conducting with Zdenek Kosler and Pedro Calderon. The prize included a $5,000 award and a yearlong assistant conductor post at the New York Philharmonic under Leonard Bernstein. Of the three, Abbado was the only one to go on to a major international career. Still feeling insufficiently prepared, however, when the year was up Abbado returned to Europe for further study.

Abbado’s specialty initially was 20th century music, but he quickly broadened his repertory to include Classical and Romantic music and opera. He usually conducted from memory. He said he had learned from observing Toscanini the importance of eye contact with musicians. But he found Toscanini’s dictatorial attitude toward musicians offensive and always treated his players with quiet respect.

His career took off after Karajan invited him in 1964 to lead the Vienna Philharmonic in Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony at the Salzburg Festival.

Abbado served as music director at La Scala from 1968 to 1986 (he had made his house debut in 1960), premiering contemporary works by Luciano Berio, Pierre Boulez, Luigi Nono, Kryzsztof Penderecki and Karlheinz Stockhausen as well as choosing unconventional versions of older works. Mussorgsky’s original version of “Boris Godunov” was his last production there.

Always interested in encouraging young musicians, in 1978 he founded the European Community Youth Orchestra. It excluded players from Eastern Europe, however, because their countries did not belong to the European Union, so in 1986 he formed the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra for musicians from Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and East Germany.

More recently, Abbado worked with the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela, the flagship of that country’s extensive music education system, and mentored its conductor, Gustavo Dudamel, now the music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

In 1979, Abbado was named music director of the London Philharmonic, and he later became its principal conductor. He made many recordings with the orchestra until he left in 1988 to concentrate his activities in Vienna.

He was appointed music director of the Vienna State Opera in 1986 and stayed until 1991, when he resigned for health reasons. Among his new productions was a critically acclaimed version of Berg’s “Wozzeck” that was recorded live and issued by Deutsche Grammophon.

In 1989, Abbado was elected chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic by the orchestra’s musicians, succeeding Karajan. He was the first Italian-born music director of that orchestra and only the fifth director in its history.

News of his appointment caused disappointment and anger in New York because Abbado reportedly had agreed to succeed Mehta at the New York Philharmonic when the latter stepped down in 1991. Abbado said that the discussions had never gone further than a few polite conversations.

Over the years, Abbado had his ups and downs with the Berlin Philharmonic, where he introduced more 20th century music than had his predecessors. In 1998, German critics and musicians complained about his choice of repertory and his rehearsal techniques. Some saw the criticism as a reaction to Abbado’s announcement earlier that year that he would not extend his contract when it expired in 2002. The tradition had been for Philharmonic music directors to remain in the post until their deaths.

Abbado said he had no complaints; he merely wanted more time for himself, “to read more, go skiing and sailing.” Other musicians rallied to his defense, and after his cancer surgery in July 2000, the complaints died down and the relationship between conductor and players was said to improve markedly. Still, he was forced to cancel most of his engagements in the latter half of the year. When his contract expired at the end of the 2001-02 season, he was succeeded by Simon Rattle.

His discography lists well over 100 recordings, mostly for Deutsche Grammophon, EMI Classics and Sony Classics. Abbado’s numerous awards included the International Ernst von Siemens music prize, one of the most prestigious awards in classical music, which he received in 1994.

His survivors include his second wife and four children.

Pasles is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.