R. Sargent Shriver dies at 95; ‘unmatched’ public servant and Kennedy in-law

R. Sargent Shriver, a lawyer who served as the social conscience of two administrations, launching the Peace Corps for his brother-in-law, President Kennedy, and leading the “war on poverty” for President Johnson, has died. He was 95.

Shriver died Tuesday at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Md., his family said in a statement. His health had been in decline since he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2003.

His illness moved his daughter, California’s then-First Lady Maria Shriver, to testify before Congress in 2009 about the disease’s “terrifying” reality. Her father was once a “walking encyclopedia, his mind a beautifully tuned instrument,” she said, but he no longer knew her name.

By then, a lifetime as a public servant — a title he embraced tirelessly and unaffectedly — was behind him. “Serve, serve, serve” was Shriver’s credo. “Because in the end, it will be the servants who save us all.”

He started such innovative social programs as VISTA, a domestic version of the Peace Corps; Head Start, an enrichment program for low-income preschoolers; the Job Corps, to provide young people with vocational skills; and the aptly named Legal Services for the Poor.

Shriver was “one of the brightest lights of the greatest generation,” President Obama said in a statement.

“Over the course of his long and distinguished career, Sarge came to embody the idea of public service,” the president said. “Of his many enduring contributions, he will perhaps best be remembered as the founding director of the Peace Corps, helping make it possible for generations of Americans to serve as ambassadors of goodwill abroad.”

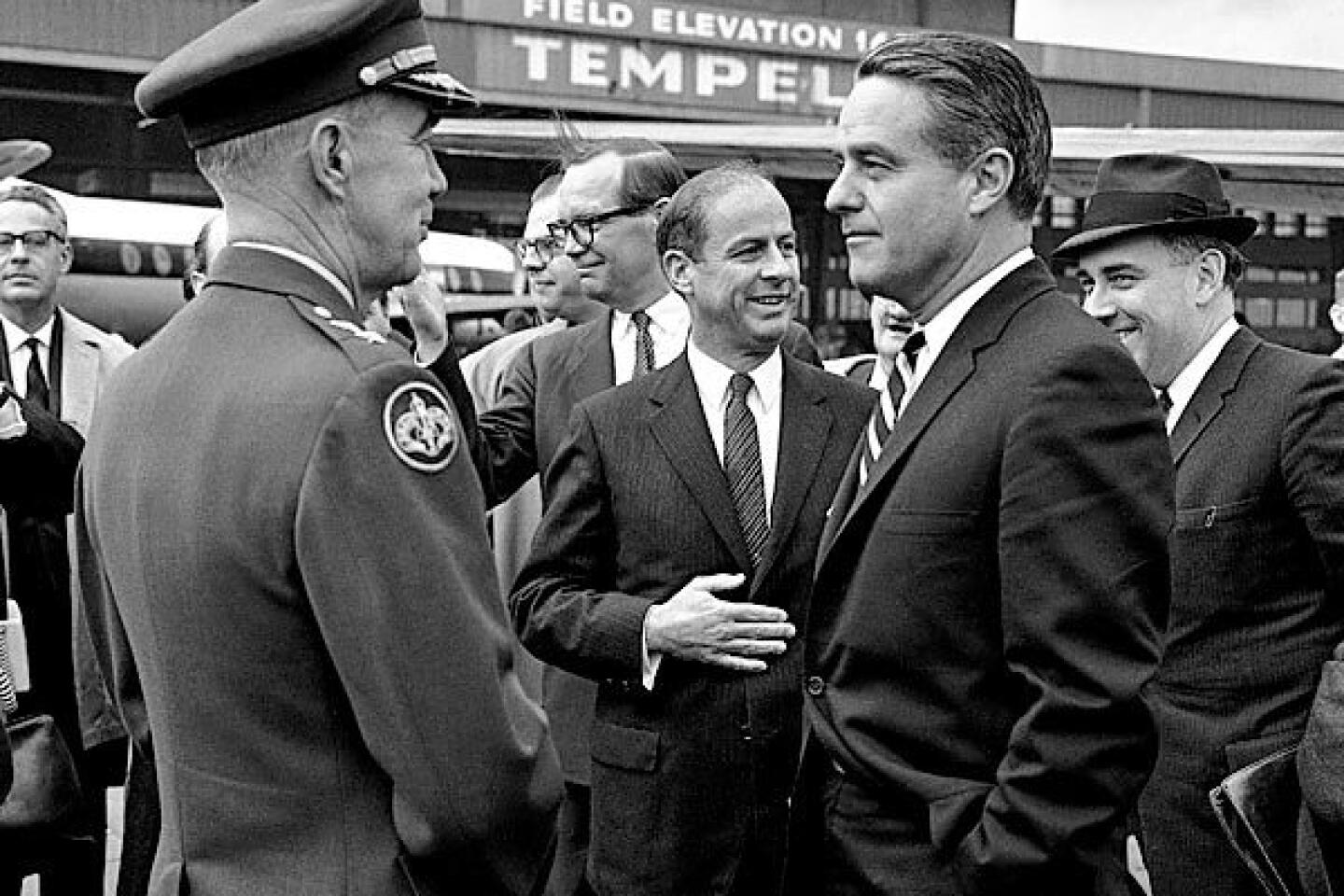

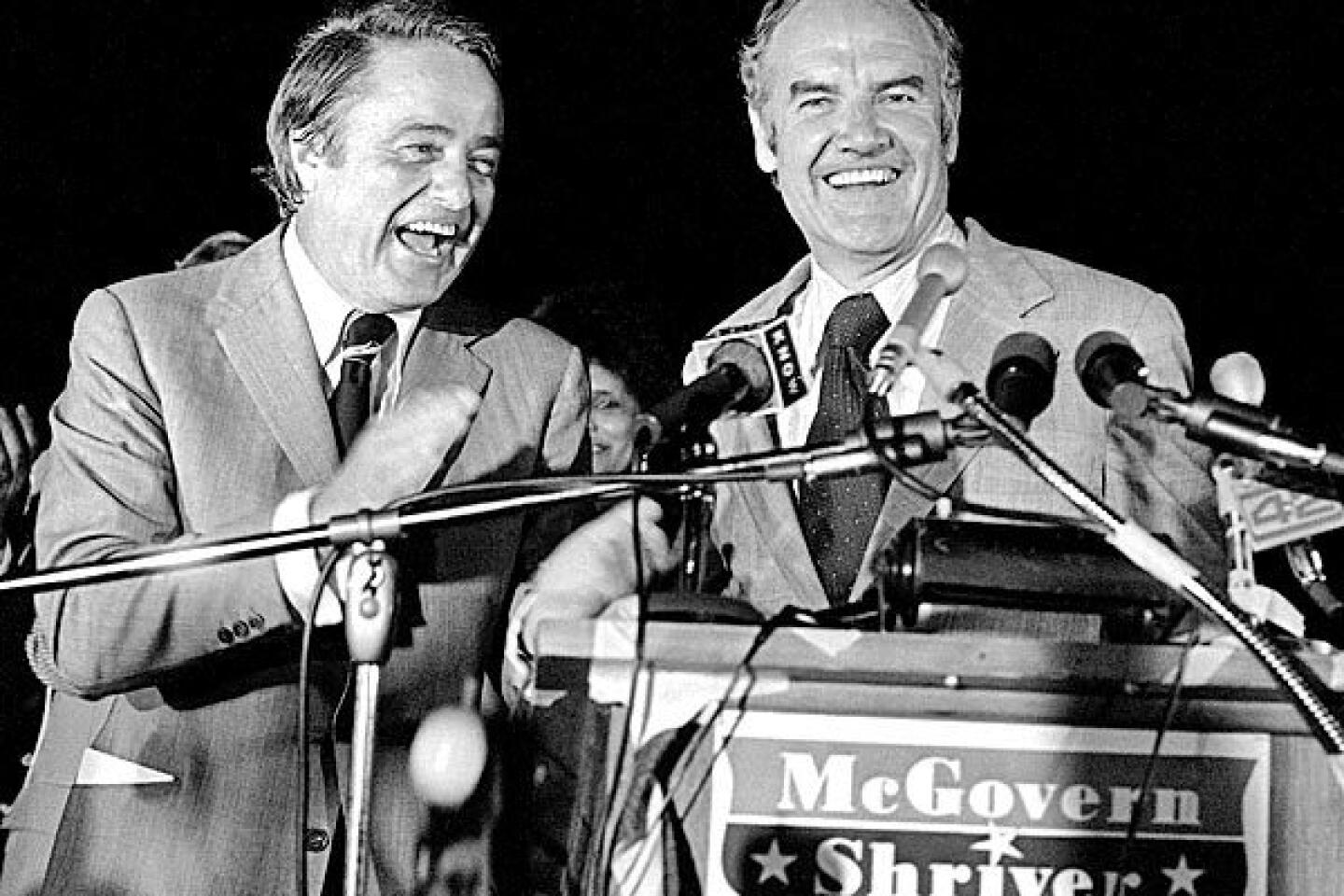

From 1968 to 1970, Shriver served as U.S. ambassador to France. In 1972, he stepped in as Sen. George McGovern’s Democratic presidential running mate after Sen. Thomas Eagleton bowed out. Four years later, Shriver briefly sought his party’s presidential nomination.

Being a member of the Kennedy family put him at the apex of power but also thwarted his political ambitions. Shriver was considering running for governor of Illinois in 1960 when family patriarch Joseph P. Kennedy told Shriver that he was needed for John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign, official Shriver biographer Scott Stossel told The Times in 2004.

When President Johnson was considering Shriver as a running mate in 1964, another Kennedy — his wife’s brother Robert — told him, “There’s not going to be a Kennedy on the ticket. And if there were, it would be me,” Stossel wrote in “Sarge: The Life and Times of Sargent Shriver” (2004).

Yet Shriver’s record of public service and innovation was “unmatched by any contemporary leader in or out of government,” Colman McCarthy wrote in 2002 in the National Catholic Reporter.

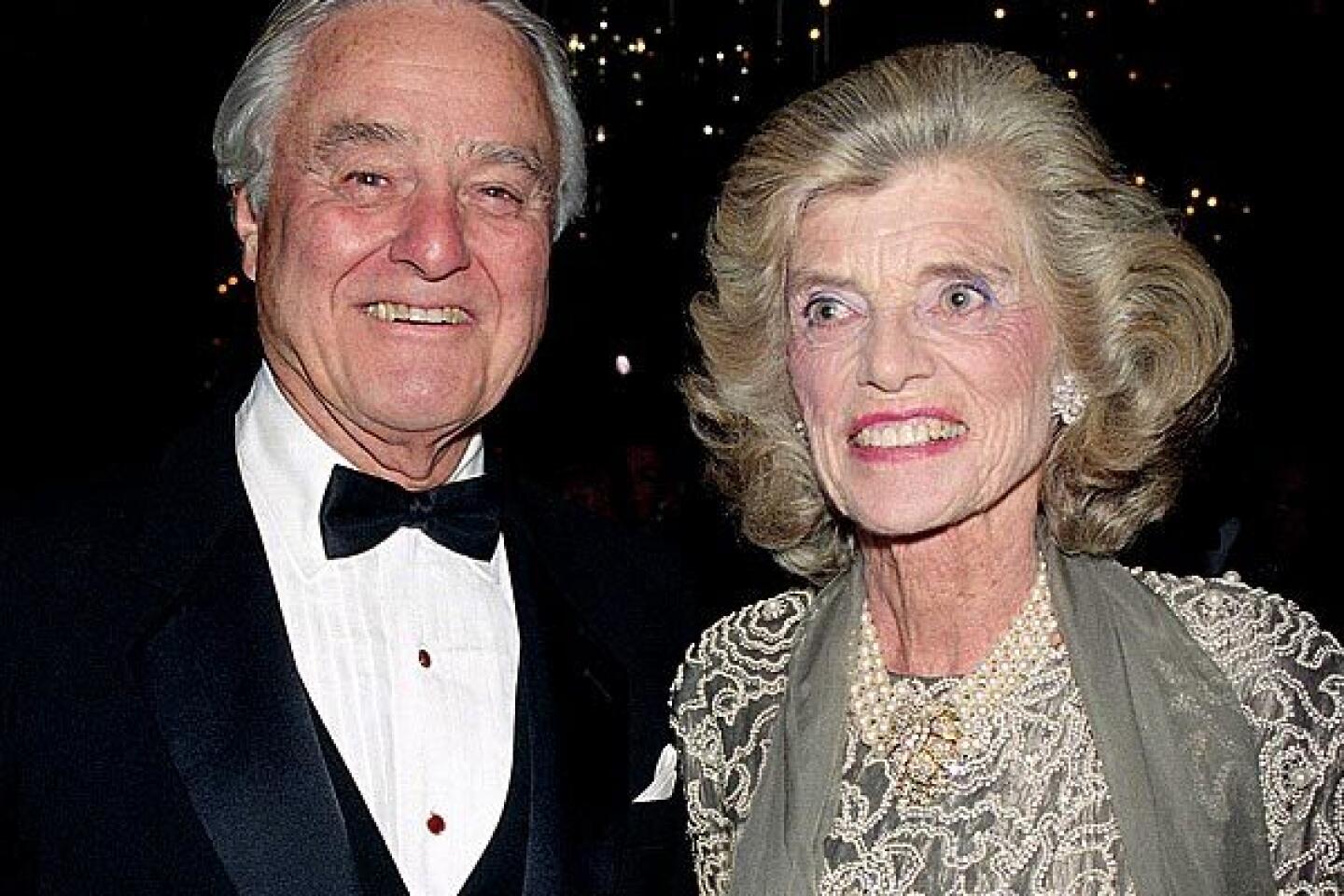

In the 1950s, Shriver was president of the Chicago Board of Education, and for decades he served on the board of the Special Olympics — the athletic games for the mentally disabled that was started in his backyard by his wife, Eunice Kennedy Shriver.

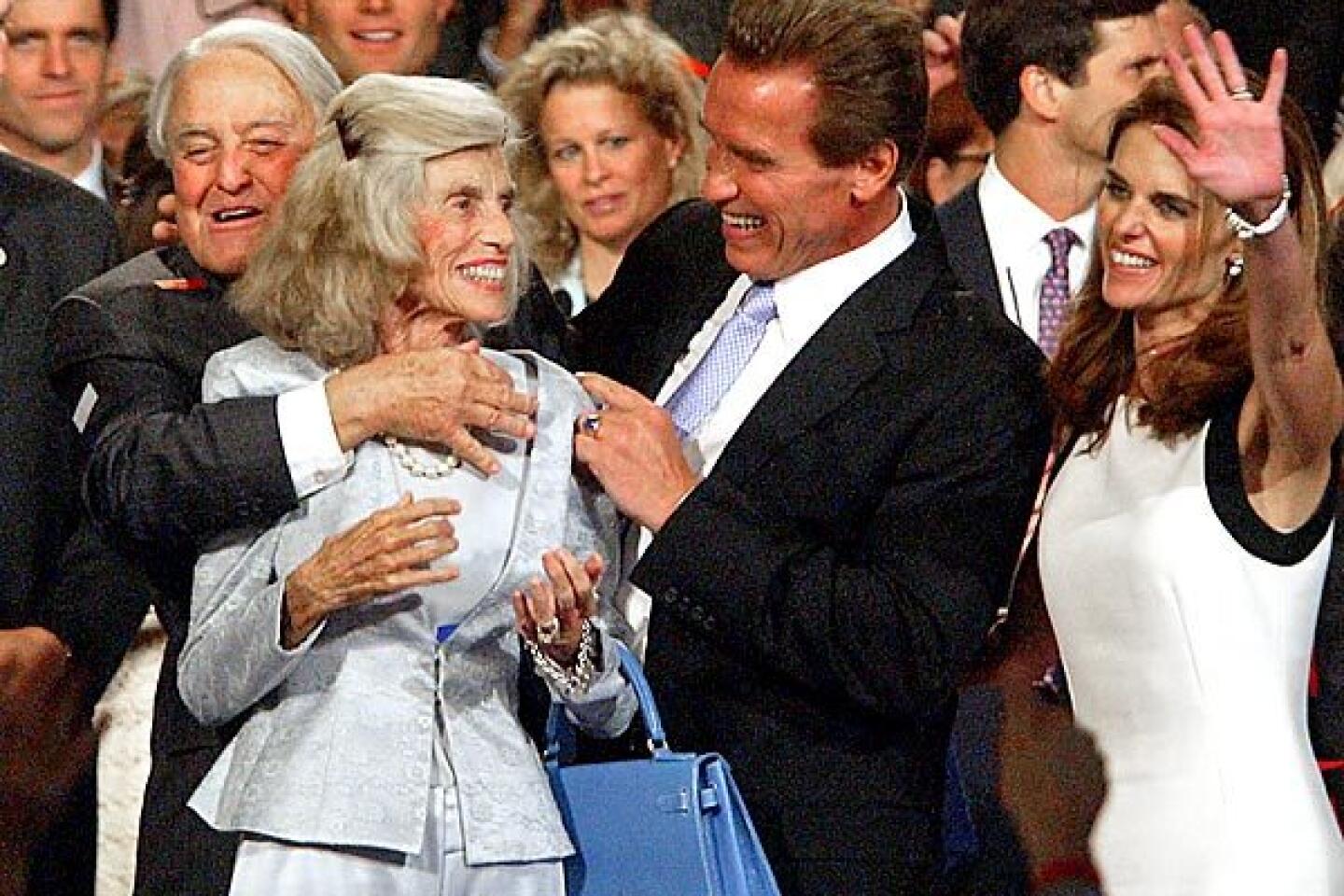

“All of these programs still exist, and they still change people’s lives,” Maria Shriver, who is married to former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, told the Associated Press in 2008.

On Tuesday, Schwarzenegger called his father-in-law’s life “a blueprint for those of us who aspire to place the needs of others above our own.”

Along with boundless energy and a commitment to those in need, Shriver was known for his relentless optimism. He also was a devout Catholic who attended Mass daily, carried a well-worn rosary and made no secret of his abiding faith.

His dedication to public service was matched only by his devotion to his family. Shriver spent seven years courting Eunice Mary Kennedy before she married him in 1953. They had been married for 56 years when she died at 88 in 2009.

Each of their five children followed their parents’ example in pursuing public endeavors. Timothy Shriver, one of their four sons, said his father taught them “to locate our deepest aspirations in the public sphere.”

Timothy, of Chevy Chase, Md., has been chairman of the Special Olympics since 1996. Eldest son Robert “Bobby” Shriver is a Santa Monica city councilman and film producer. Mark, who lives in Bethesda, was a member of the Maryland Legislature. Anthony, of Miami Beach, Fla., runs Best Buddies, which pairs college students with the mentally disabled. Maria, a former network news reporter who lives in Los Angeles, won two Emmys in 2009 for documentaries on Alzheimer’s that she produced. One was based on a children’s book she wrote, “Grandpa, Do You Know Who I Am?”

Robert Sargent Shriver was born Nov. 19, 1915, in Westminster, Md., to Robert and Hilda Shriver.

The Depression financially ruined his stockbroker father, and it was through the largesse of family and friends that Shriver attended Yale University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1938 and a law degree three years later.

During World War II, he spent five years in the Navy and served in the Pacific.

In 1946, he took a job as an assistant editor at Newsweek magazine and met Joseph P. Kennedy, who two years later asked Shriver to manage the giant Chicago Merchandise Mart.

When Shriver fell in love with his boss’ daughter, he became a close and valued member of the famously clannish Kennedy family.

“Our brother-in-law became our brother,” Sen. Edward M. Kennedy said in 2005. “We love him in our family.”

Another of Shriver’s brothers-in-law, John Kennedy — then a Democratic senator from Massachusetts — turned to Shriver in 1960 for help with his quest for the presidency. As manager of the civil rights arm of the campaign, Shriver engineered a feat that some say tipped the close election in Kennedy’s favor.

When a young African American minister, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., was jailed in Alabama for civil disobedience, Shriver persuaded Kennedy to reach out to King and his wife, Coretta. The call was credited with helping to cement the crucial black vote for Kennedy.

The day after his inauguration, Kennedy asked Shriver to help him develop a program for young Americans to serve overseas. “Make it big,” the president counseled. “Be fast, and be bold.”

It was Shriver’s idea to send Americans to the farthest reaches of the globe, bringing with them education, technology and a sense of fellowship that Shriver believed could break down barriers and win grass-roots respect for the U.S. He promised low pay, primitive conditions — and the reward of translating ideals into action.

His challenge was: “Be somebody. Join the Peace Corps.” Of recruits, he required just three qualities: courage, commitment and conviction.

Lewis Butler, a California lawyer, said Shriver called him in 1961 and asked him to head the program in Malaysia. The concept was vague, but Shriver was utterly determined, Butler said. He recalled being unsure where Malaysia was.

“The first thing I did was run out and get a map so we could start the Peace Corps,” he remembered. “I said, ‘What are we supposed to do?’ And he said, ‘I don’t know.’ ”

In 1962, when the program was already running in high gear, Shriver visited the volunteers in Malaysia and asked a nurse running a leprosy clinic if he could help. Soon Shriver was passing out bandages and medication to lepers, Butler said, and speaking to them as if they were heads of state.

“He was not just the head of the Peace Corps or its boss,” Butler said. “He was the personification of its ideals.”

Peace Corps volunteers arrived in five countries in 1961. In just under six years, Shriver developed programs in 55 countries with more than 14,500 volunteers. Since its inception, the Peace Corps has sent 200,000 volunteers to 139 countries. Today, more than 8,500 volunteers are serving in 77 countries.

After President Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, President Johnson asked Shriver to tackle the problem of poverty in the United States. At a 1964 news conference announcing his appointment as director of the Office of Economic Opportunity, a reporter demanded: “Mr. Shriver, do you really believe that poverty can be wiped out?”

Without hesitation, he replied, “Yes. I do.”

In the next four years, Shriver unleashed a flurry of new programs. Using the Peace Corps as his model, Shriver crafted VISTA, a volunteer service corps aimed at U.S. cities. The acronym stood for Volunteers in Service to America. Head Start was designed to prepare underprivileged preschoolers for elementary school, just as private day care and nursery schools served more affluent children.

Community Action provided low-income housing. Foster Grandparents matched elderly volunteers with young children. Legal Services guaranteed lawyers to poor people. Indian and Migrant Opportunities brought training to Native Americans. Neighborhood Health Services targeted community medical needs.

Each of those programs remains in place today.

Political analyst Mark Shields met Shriver in 1972, when Shriver replaced Eagleton on what turned out to be a losing Democratic presidential ticket. (Eagleton left the race when it was disclosed that he had been hospitalized for depression.)

As the campaign’s political director, Shields discovered Shriver’s insatiable appetite for ideas. “Ideas to Sarge had no gender. They had no sex or race or age,” Shields said. “He just loved ideas.”

Although he was a man of deep faith, Shriver was also a supreme rationalist, said the Rev. Bryan Hehir, a Catholic priest and longtime friend.

“He was convinced that you could solve anything if you thought about it long enough,” said Hehir, a professor of religion and public life at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. “He thought the human mind was made to conquer the Earth, and anybody who doubted that, he really didn’t want to have anything to do with.”

Luckily, Shriver found ample companionship. He collected people, said biographer Stossel: “Once you got absorbed into the Shriver orbit, you could not escape.”

He found allies on the ski slopes, in churches and in coffee shops. He drafted them into his schemes for social change simply by asking for their help.

At 79, Shriver received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Clinton. “In my lifetime, America has never had a warrior for peace and against poverty, a warrior to make peace the noblest of endeavors, like Sarge Shriver,” the president said at the 1994 ceremony.

When he was 90, Boston’s John F. Kennedy Library organized a forum in Shriver’s honor. He was frail in the winter of 2005. Alzheimer’s was stealing his memory, and his hair had turned snow white. Using a cane to help him walk, he entered with his wife beside him. The audience burst into cheers.

Onstage, his old friend, Kennedy advisor Harris Wofford, had been talking about Shriver’s days in Chicago but abruptly changed course, declaring, “Here’s the man who should have been president.”

Shriver raised his arms as if to encircle the crowd of 500. “Hooray!” he shouted — and then beamed a smile that, for all of its years, had lost none of its magnetism.

In addition to his five children, Shriver is survived by 19 grandchildren.

Funeral and memorial details will be posted at https://www.sargentshriver.org.

Mehren is a former Times staff writer.

Times staff writer Valerie J. Nelson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.