Sam Shepard, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and Oscar-nominated actor, dies at 73

Sam Shepard, paragon playwright of the American West, was born to roam.

With a father who was an Army officer and sometime farmer and a mother who was a teacher, Shepard — born in 1943, the oldest of three — spent his childhood bouncing around the heartland. This would later inform his writing, which often explored the fringes of society and the failure of the nuclear family.

For the record:

2:46 a.m. Nov. 17, 2024An earlier version of this article cited an incorrect year of birth for Hannah Jane Shepard. It was 1986, not 1985.

Shepard eventually found a home in California — in Duarte, where he would graduate high school, and in Chico, where he worked as a stable hand. But eventually his roaming would take him east, to New York City and the stage that would make him a legend.

Shepard died Thursday, surrounded by family at his home in Kentucky, of complications from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), often called Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was 73.

Chris Boneau, a spokesman for Shepard’s family, confirmed Shepard’s death to The Times in a statement. “The family requests privacy at this difficult time,” he said.

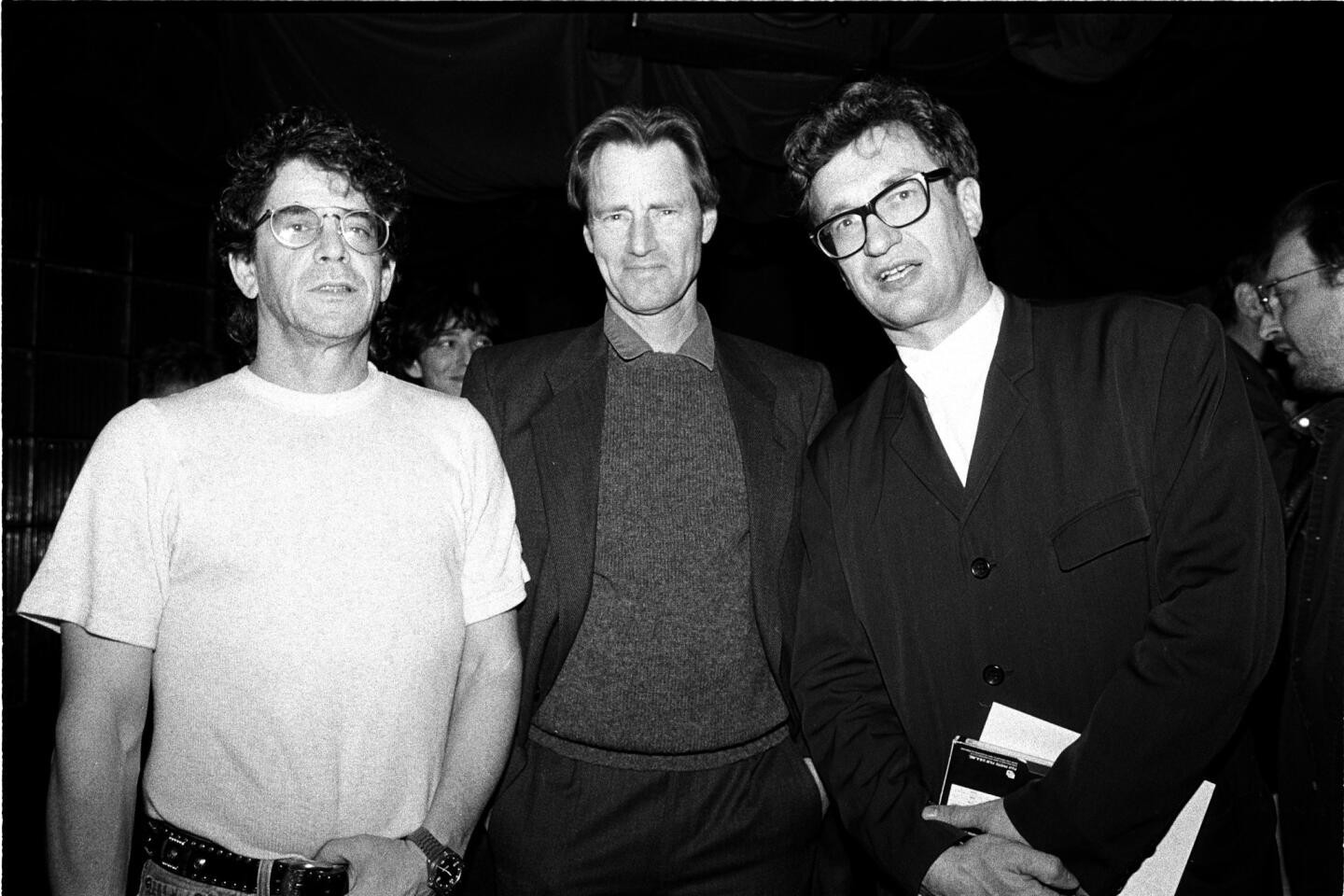

Shepard made his earliest impression on the New York theater scene in 1966, when he took home Obie Awards for three plays: “Chicago,” “Red Cross” and “Icarus’ Mother.” The playwright would go on to win 10 more Obie Awards in his distinguished career.

In 1969, Shepard married actress O-Lan Jones, with whom he had one son, Jesse Mojo Shepard, in 1970. As Shepard continued to write, he also began acting, appearing as the charming land baron known only as “The Farmer” in Terrence Malick’s 1978 classic film “Days of Heaven.”

That same year, Shepard wrote his crowning achievement, “Buried Child.”

Centering around a family haunted by the past as it comes together in an aging Illinois farmhouse, the play reflects shades of Shepard’s own relationship with his father, whom the playwright described as alcoholic.

Although often described as avant-garde, Shepard’s relationship with the past would define future plays as well.

“For Shepard, love is a repetition of the past,” wrote Times theater critic Charles McNulty in a review of a 2015 revival of “Fool for Love,” “the family drama reenacted against our will as we ricochet between the desire to be connected and the need to be autonomously alone.”

Shepard won the Pulitzer Prize in 1979 for “Buried Child.” That year a Times review of a Los Angeles production called the play “creepy and shadowed,” noting that Shepard’s story unspools like a dream meant to be divined, not parsed. The review for a South Coast Repertory production in Costa Mesa seven years later noted just how viscerally the play explored the wreckage of an American family: “It’s up to the artist to put us face to face with the inexplicable, the fated, the curse signed into being by one’s own hand.”

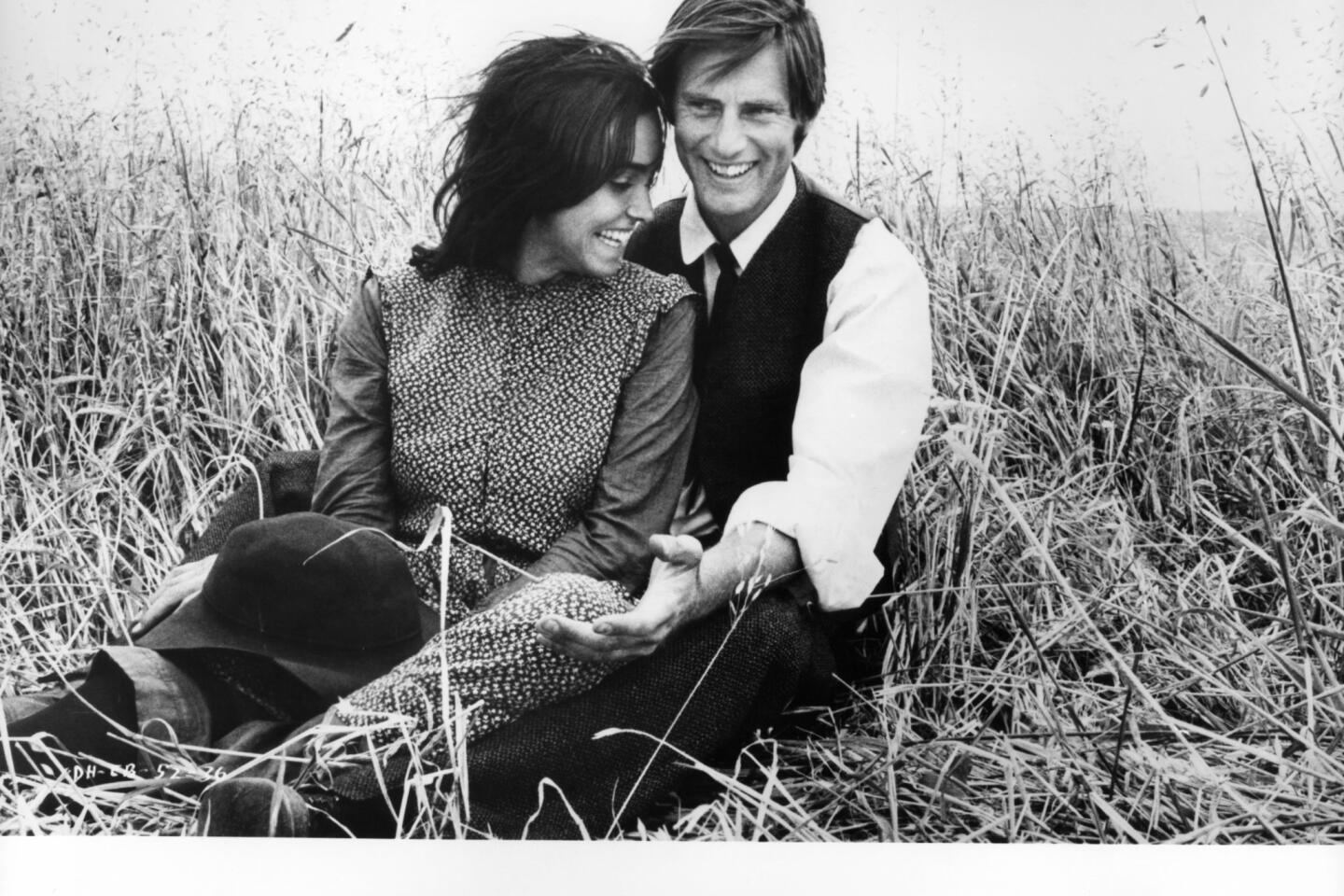

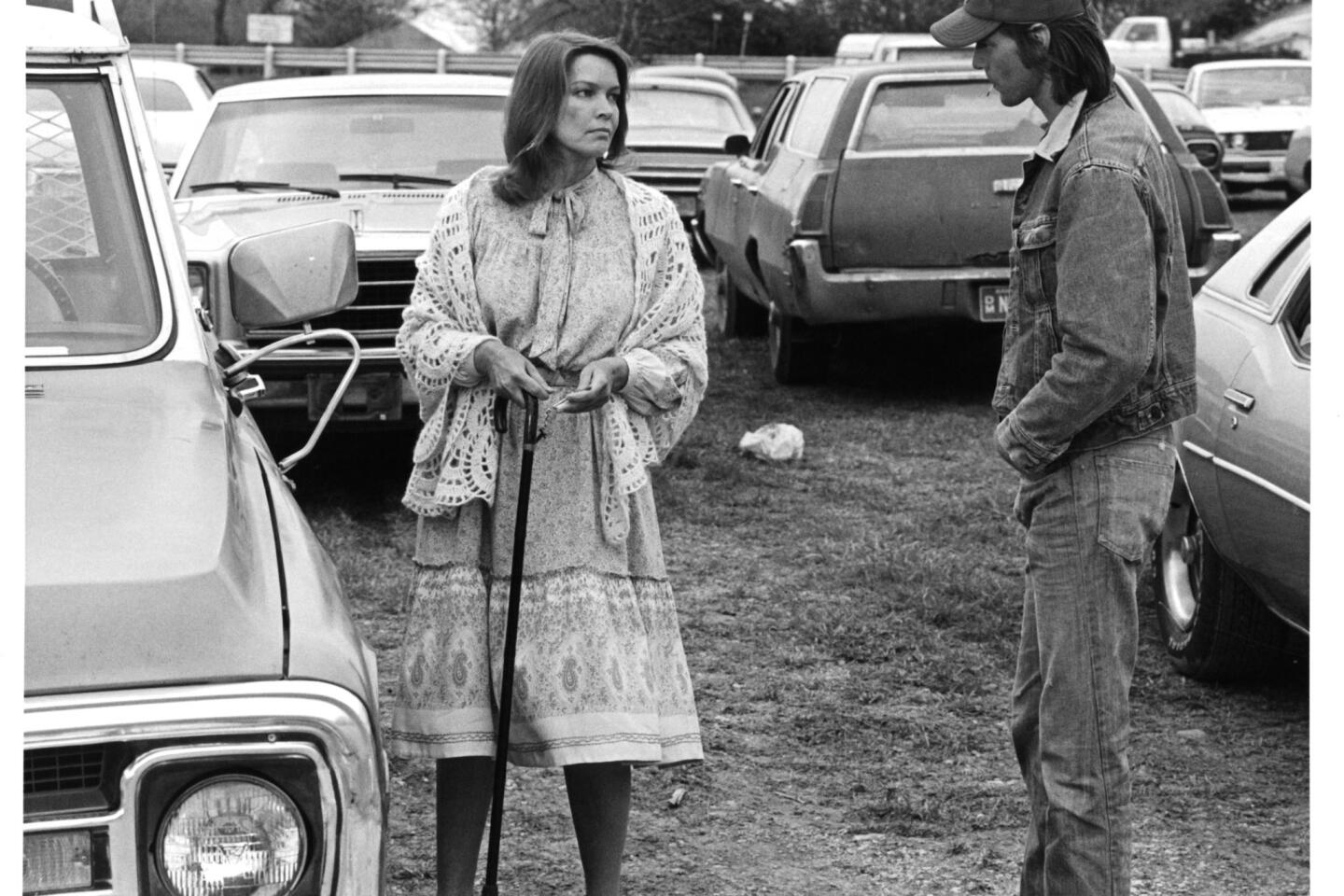

In 1982, Shepard starred in “Frances” alongside Jessica Lange and began a decades-spanning romantic relationship. After divorcing Jones in 1984, Shepard had two children with Lange — Hannah Jane Shepard in 1986 and Samuel Walker Shepard in 1987. The couple stayed together for more than 20 years.

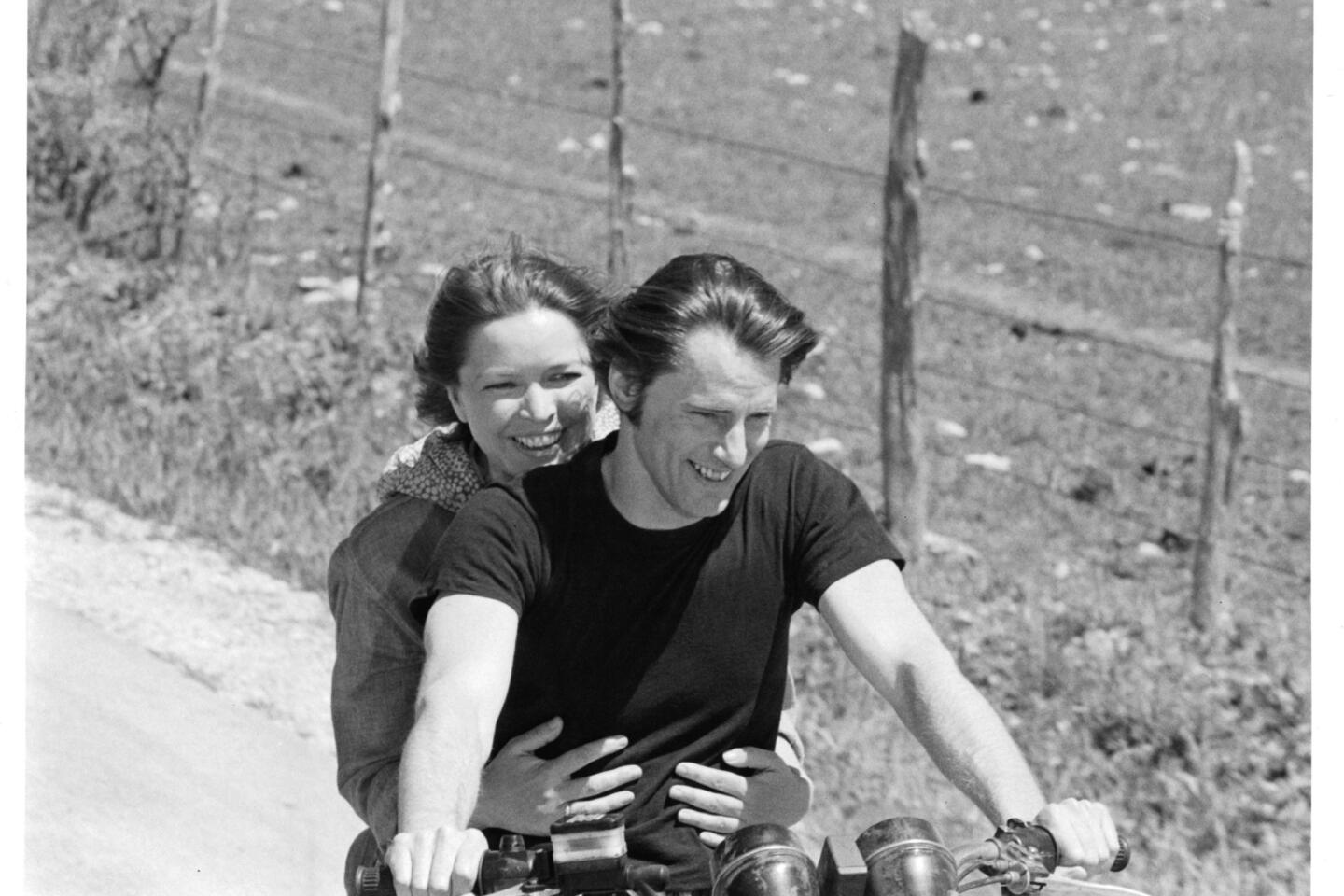

Shepard starred in his most celebrated role in 1983, portraying pilot Chuck Yeager in “The Right Stuff.”

“The most righteous right stuff is the private property of Air Force test pilot Chuck Yeager, played by Sam Shepard in a manner guaranteed to fill the gap created when Gary Cooper left us,” Times film critic Sheila Benson said of Shepard’s easy masculinity in her original review of the film.

Shepard’s performance earned him an Academy Award nomination for best supporting actor.

This vacillation between artistic interests and latent embodiment of the long-lost cowboy would come to define Shepard throughout his career.

“No one knows better than Sam Shepard that the true American West is gone forever,” then-New York Times theater critic Frank Rich wrote of the 1983 debut of “Fool for Love,” “ but there may be no writer alive more gifted at reinventing it out of pure literary air,” adding a year later in a contemplation of “True West” that “Mr. Shepard, as much as any contemporary American playwright, gives our theater its claim to seriousness and its connection to other art.”

That ability to conjure a time or a mindset long gone, if indeed it had ever existed, fueled his work both in front of the camera and behind it.

“I still think it all comes from the same place, but it’s great to be able to change it up,” Shepard told The Times in 2011. “It would be like riding the same horse all the time.

“To sing a song is quite different than to write a poem. I’m not and never will be a novelist, but to write a novel is not the same thing as writing a play. There is a difference in form, but essentially what you’re after is the same thing,” Shepard concluded.

It was that same interview with The Times, conducted by phone, that had to be delayed when Shepard, quite literally, had to see a man about a horse.

“I was at a horse sale yesterday, and it was just all-consuming,” Shepard said.

He went on to explain that he didn’t fly when traveling around the continental United States, preferring instead to explore the open road.

Though that may sound idyllic, Shepard was not an artist who shied from the ugliness of the world.

In his 2004 play “The God of Hell,” Shepard tackled a post-9/11 country besieged in equal parts by patriotism and fascism, sometimes disguised as the same thing.

“We’ve never known who we are as a country, only how we’d like to define ourselves: idealistic, good, positive, saving the world for democracy, right?” Shepard told The Times in 2006 before the show opened at the Geffen Playhouse. “We have this inability to face what has become of us so all we get is this propaganda ... the lies, the evasions, the refusal to tell the truth.”

But all hope was not lost, according to Shepard.

“The hopeful part is that at least they see things as they really are and don’t attempt to disguise it in other forms. And the more people see things as they are, the more hope there may be to bring about something different,” he said.

Shepard was not without his own demons, however.

In 2009, he was arrested for drunk driving in Illinois and was sentenced to 24 months probation, alcohol education classes and 100 hours of community service. In 2015, he was arrested for aggravated drunk driving in New Mexico, though charges were later dismissed, despite Shepard failing a field sobriety test.

Shepard remained active in the twilight of his career, publishing the play “A Particle of Dread,” his take on Oedipus, in 2014, and appearing in Netflix’s “Bloodline” throughout the show’s three-season run.

Survivors include his children, Jesse, Hannah and Walker Shepard, and his sisters, Sandy and Roxanne Rogers.

Funeral arrangements remain private. Plans for a public memorial have not been determined.

UPDATES:

11:15 a.m.: This story has been updated throughout with Times staff reporting.

The first version of this story was published at 8:25 a.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.