PALM SPRINGS — Alvin Taylor and his wife, Delia Ruiz Taylor, look out over a vacant lot owned by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians and let childhood memories flood the empty space.

In the late 1950s and early 60s, when the pair were in grade school, the lot was part of the square-mile tract known as Section 14. It was about the only place in town where workers of color, Indigenous Americans and other marginalized people could live in a desert playground that catered to the rich, glamorous and white.

Neighbors looked out for one another in Section 14, the couple said, and unlike in the rest of the city, where many of the tract’s residents worked as cooks, cleaners and construction workers, nobody seemed to care about the color of your skin.

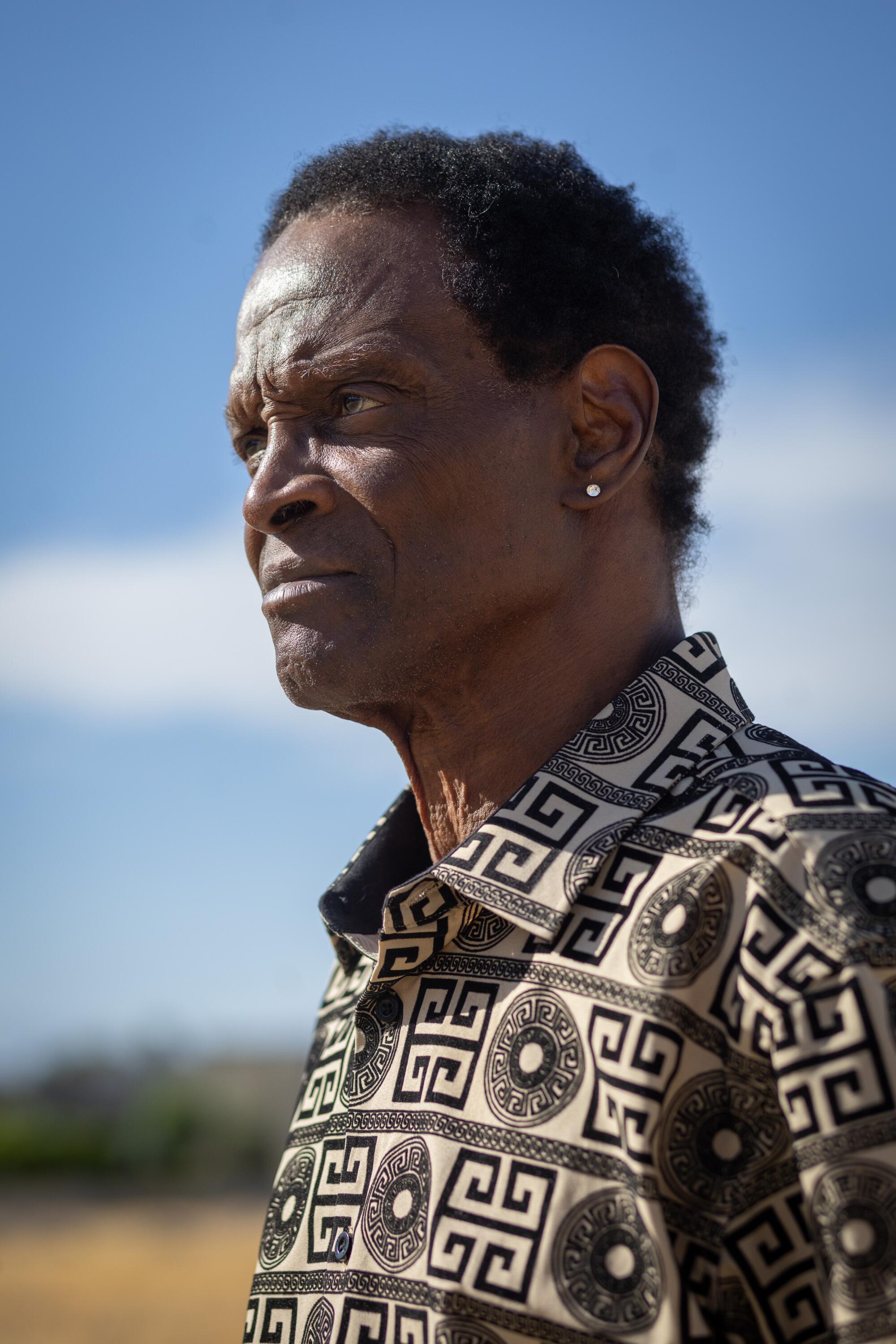

“We were safe and comfortable with it being Indian land because white people didn’t want us living anywhere else,” said Alvin Taylor, now 71. “On the reservation, we were all one big community.”

That spirit of fellowship prompted Taylor to join an experimental theater production that dramatizes the neighborhood’s distinct character and explores the complexities of its demise: “Displacement: Stories From Section 14.”

Taylor wants audiences to know that a whole world was destroyed when his home, Ruiz’s house and dozens of others in Section 14 were either razed or burned to the ground between 1959 and 1968 in acts that the state attorney general’s office said amounted to “a city-engineered holocaust.”

The 40 Acres Conservation League is on a mission to establish an open space where Black Californians and other people of color can feel at home in nature.

The series of staged readings by Green Room Theatre Co. is set to run June 22 and 23 at United Methodist Church of Palm Springs and June 28 to 30 at the Coachella Library’s Community Room.

The production comes as 350 survivors from Section 14 and more than 1,000 descendants seek restitution for the profound loss and trauma their families faced. It also takes place during a statewide reckoning over slavery and racial injustice. A package of historic reparations bills is moving through the state Legislature, and Indigenous Californians have made their own strides in safeguarding, reclaiming and co-stewarding stolen ancestral lands.

Although some Palm Springs residents dispute that racial hostility led to the evictions, city officials issued an apology in 2021 and recently pledged to “right that wrong.” The city is engaged in settlement talks with the Palm Springs Section 14 Survivors group, which Taylor helped found before stepping away recently.

“Everything was taken away from us,” Taylor said of the damage families such as his suffered.

But how do you calculate in dollars and cents — or capture in a community theater production — the loss of belonging and social harmony that survivors say they discovered at Section 14? Further complicating the story, the land was marked by trauma long before Black and brown transplants built their dwellings on it.

The tribe has been largely silent in the restitution debate, but at the Agua Caliente Cultural Museum, video displays explain how their land was seized and divided into parcels as newcomers flocked to the desert.

With few options to raise revenue for the tribe, individual Agua Caliente members had rented land to newcomers of color who were barred by real estate covenants from living elsewhere in Palm Springs.

By the late 1950s, though, Agua Caliente property owners were forced to pay for court-appointed conservators to control the management of their plots, including terminating leases and working with the city to carry out evictions, according to a 2019 article in the Smithsonian’s American Indian Magazine about the tribe’s struggle for sovereignty.

It’s a dark and messy history. The staged reading isn’t meant to relitigate past wrongs but to “uplift the voices, the truth and the humanity of the people who lived in that space” and help audiences relate to their plight, said Allison Scarlet Jaye, one of the playwrights.

There were good times mixed in with the bad, the Taylors said.

The Wilton Rancheria tribe have fought for years to reclaim stolen lands. A 77-acre parcel outside Sacramento is theirs once more.

Taylor, who is Black American, and Ruiz Taylor, who is Mexican American, smile when remembering how the dirt roads in Section 14 were so narrow that cars had to scoot over to pass each other. Kids would stroll to the nearby Fosters Freeze for soft-serve ice cream.

Taylor fondly impersonates the roving sweet potato vendor who shouted into his loudspeaker: “All you little children playing in the sand, go tell your mama, ‘Here’s the Sweet Potato Man!’”

Ruiz Taylor happily recalls walking alongside a relative of her cousin who traveled up from Tijuana to sell tamales from her little red wagon.

When the evictions started, Taylor says, his family and others bunked in the homes of generous neighbors in Section 14, only to have to move again when those families’ houses were slated for demolition too. Taylor was just 8 at the time. He remembers feeling as if he and his neighbors were being herded like animals.

“As we continued to move from one house to the other house — coming home and seeing the house burn and smelling the smoke, seeing the bulldozers tearing down the structures — it was a horrifying ordeal,” Taylor said. “Believe it or not, I still have nightmares.”

Ruiz Taylor, 72, says she was about to enter the seventh grade when her family moved out. Banks refused to lend her family money because they were Latino. When they found a place on the dusty outskirts of town, white neighbors hurled racial insults and yelled for them to “go back to Mexico.” One young man shot her in the leg with a BB gun, she says.

“When they took us out of here, oh, we hated it,” she said. “I was deathly afraid. I didn’t know about anything else but living here.”

Taylor suppressed his own mental anguish as he became a renowned drummer. Little Richard saw him sit in with a band performing at the Palm Springs Biltmore Hotel when he was a 14-year-old busboy, and before Taylor knew it, he was opening for Elvis Presley in Vegas. He played with the likes of Tina Turner, Bill Withers, Jimi Hendrix, Ron Wood and Cher, recorded music at George Harrison’s house, partied on the Concorde with Elton John and built a castle for himself in the Hollywood Hills.

Living a life of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll offered a distraction, for a while.

Taylor says he finally got sober with help from his friend Eric Clapton. Years of therapy and moving back to his hometown have helped Taylor fully understand why he needed to escape from himself so badly. He credits his continued recovery to Ruiz Taylor, his boyhood crush and a fellow survivor whom he married in 2012.

While the rocker has a plaque on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars, across the street from Presley’s, he says he still suffers from post-traumatic stress because of what his family endured just a few minutes’ drive away.

He hopes the theater production — in which he serves as a creative consultant and a cast member — will help audiences see the tragedy of Section 14 in a clearer light.

Indigenous Californians want President Biden to establish a national monument in a stretch of desert that is both an ecological wonder and a window into their cultures.

Taylor recently parted ways with the survivors group, which is helmed by his sister Pearl Devers and represented by the Los Angeles civil rights attorney Areva Martin, because of internal conflicts over a strategy that he believes focuses too much on anti-Black racism as a cause of the evictions.

Taylor agrees that white supremacy runs through Palm Springs’s history and that white residents today must be willing to own up to that legacy. But he believes the story of Section 14 was more about the erasure of a loving and inclusive working-class neighborhood that didn’t mesh with the city’s glamorous image.

Martin said that while she’s not opposed to a play about Section 14, she believes the timing is premature and that it’s unwise for survivors to take part, given that the group is in sensitive legal talks with the city.

She rejected the notion that the group has become too focused on Black survivors, noting that the group has called for establishing a racial and cultural healing center where survivors of all backgrounds can share their stories. Martin said that the group has made efforts to acknowledge and celebrate the Latino survivors and that it has welcomed support from the city’s large LGBTQ+ community.

In response to an L.A. Times request for comment about Taylor’s concerns and his participation in the production, the Palm Springs Section 14 group emailed a statement from its governing board, which includes Devers.

“We know that in every fight for justice, there are forces that will seek to divide us and distract us from the mission at hand,” the statement reads. “As we always have, we remain singularly focused on reaching a resolution in partnership with the City of Palm Springs. That — and only that — will remain our top priority until there is restitution.”

Taylor says he wants only to make sure the staged reading accurately captures the experiences of all who called Section 14 home.

“It’s my feeling that as a Section 14 survivor and a founding member of the survivors group that if someone was to go and do a play, they’ve got to talk to someone who was there,” he said.

During one recent rehearsal, cast members from different racial backgrounds read pieces of narration and dialogue that they’ve written and that Jaye and fellow playwright Jerome Joseph Gentes will shape into a final script.

Taylor, his slim frame draped in a button-down shirt with a jazzy geometric print, offers historical details to guide the group discussion.

Throughout the rehearsal, the actors portray Section 14 as a bubble — geographically attached to Palm Springs, yet socially sealed off from it. Until the mid-1960s, most of the city’s resorts, nightspots and country clubs were off-limits to patrons of color and Jews. Taylor says his mother crossed back and forth between those worlds because she worked as a housekeeper for Lucille Ball.

Many believe white Americans suffer higher rates of premature death from addiction, overdoses and mental health. Researchers say that’s false.

Director and theater company Executive Artistic Director David Catanzarite says his focus as an artist with a mixed background is to illuminate the overlooked stories of Black and brown people in the Coachella Valley. While the Section 14 tragedy is well-documented, those historical facts contain many layers that make for rich material on which to base a fictional account, he said.

Above all, Catanzarite wants the production to help Palm Springs reckon with its past and move toward collective healing.

“This is a truth and reconciliation project,” he said.

Gentes, a recent transplant to Palm Springs who is descended from the Gros Ventre and Standing Rock tribes, says he hopes that Section 14 survivors get justice. But he wonders: Is there ever a perfect moment to engage artistically with a trauma that sweeps up so many lives and reveals so much about a city’s social fabric?

“Theater can at least jump-start the conversation,” Gentes said.

For Taylor, who’s about to publish a memoir documenting his life and career, truth-telling remains an agonizing endeavor.

“I could start crying any minute,” he said by phone before revisiting Section 14 with his wife.

Taylor says he has friends from the old Section 14 who are still lost and living with drug and alcohol problems that he believes stem from the traumas they endured as survivors. He wants his foray into theater to show them that it’s healthy to examine the root causes of your life crises.

At the site with Ruiz Taylor, Taylor’s voice cracks as he reflects on what his neighborhood meant to him. Overgrown grass yellows in the hot desert sun. Only a few concrete foundations remain where homes once stood.

Mt. San Jacinto rises more than 10,000 feet above a skyline of glistening palms.

It is a bittersweet opportunity for Taylor to contemplate the meaning of home and the value of reclaiming — at least on an emotional level — where you came from.