Roger Wilkins, activist and historian whose Watergate editorials helped win a Pulitzer, dies at 85

Reporting from Washington D.C. — Roger Wilkins, a historian, journalist and activist who held a key civil rights post in President Johnson’s administration and helped the Washington Post win a Pulitzer for its Watergate coverage, died Sunday, relatives said. He was 85.

Wilkins, most recently a history professor at George Mason University, died at an assisted-living facility in Kensington, Md., his wife, Patricia King, and his daughter Elizabeth Wilkins said. The cause was complications from dementia, they said.

His uncle Roy Wilkins was the longtime executive director of the NAACP. A lifetime later, his daughter Elizabeth worked in the presidential campaign of then-Sen. Barack Obama.

Wilkins said in spring 2008 that the presidential candidacies of a woman and a black man “would have been fodder for a fantasy movie” when he graduated from college 55 years earlier.

“Today, whatever our problems are, we have a vastly different and better country than the one we lived in in 1953,” Wilkins told University of Southern Maine graduates.

From the mid-1960s to the early 1980s, he worked for the Johnson administration, the Ford Foundation, the Washington Post and the New York Times. In his 1982 autobiography, “A Man’s Life,” he described the frustrations of being “the lead black in white institutions for 16 years.”

In a Washington Post review, famed author James Baldwin wrote that Wilkins “has written a most beautiful book, has delivered an impeccable testimony out of that implacable private place where a man either lives or dies.”

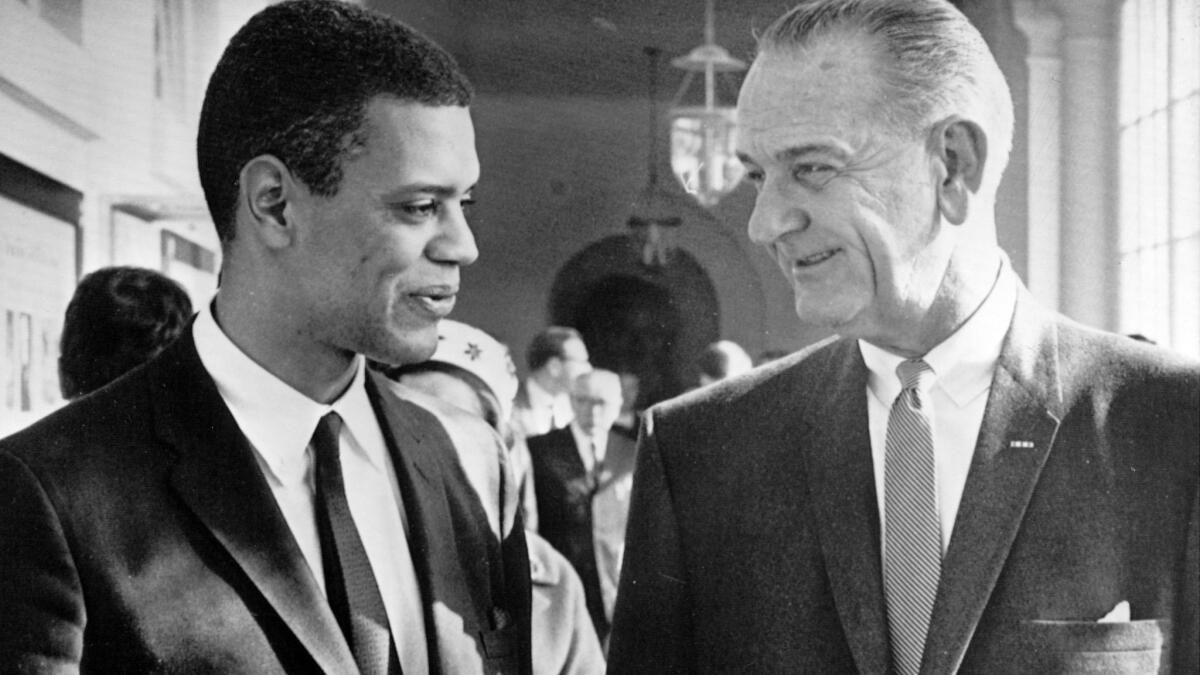

In 1965 Johnson tapped Wilkins to head the federal Community Relations Service, which was created by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to mediate racial disputes and foster progress in black communities.

The New York Times said Johnson told him it would be “the toughest job ever given any Negro in the Federal Government.... You have one mandate — to do what is right.”

As many cities were racked by rioting in the mid-1960s, Wilkins advocated efforts to improve conditions there. “We have to change the way people live,” he said in the Times in 1967. “All the rest is Band-Aids and lollipops.”

He joined the Ford Foundation when Johnson left office in early 1969. In 1970, he wrote a Washington Post essay about being almost the only black person at the Gridiron Dinner, the annual Washington frolic of the male power elite. He wrote that its convivial insider jokes about such things as President Nixon’s “Southern strategy” amounted to “a depressing display of gross insensitivity and both conscious and unconscious racism.”

He wound up leaving the Ford Foundation for journalism. His Washington Post editorials in the early months of the Watergate scandal in 1972 contributed to the paper’s 1973 Pulitzer Prize for public service, a staff award.

Wilkins left the Post in 1974 to join the New York Times, doing commentary on the final stages of the Watergate scandal from his new post.

Among his other books were “Jefferson’s Pillow: The Founding Fathers and the Dilemma of Black Patriotism,” 2001; and “Quiet Riots: Race and Poverty in the United States,” a 1988 look back at the Kerner Commission’s 1968 report on urban unrest that Wilkins co-edited with former Sen. Fred R. Harris, who had been a commission member.

In a 1992 Associated Press story on black and white relations, he criticized the notion among some black people that they should stay away from the mainstream white culture lest they be guilty of “selling out” or “acting white.”

“If we tried to enforce a black orthodoxy, then we would fall into the white folks’ trap. They would love for us to all think alike,” Wilkins said.

In a 2009 essay in AARP the Magazine, he recalled his feelings about Obama’s win.

He wrote that in the early stages of the race, he believed Obama had “no chance. This man’s been in the Senate for 15 minutes, and white people just aren’t going to vote for a new black guy. ... I thought back to the scores of highly intelligent black men and women I’d known over my lifetime who never even passed Go because whites did not believe they could do serious work.”

He said despite his doubts, he still advised his daughter to join the campaign, telling her, “This is your generation’s Selma, and you dare not miss it.” And as Obama began winning primaries, “I caught that fire.”

In his 1982 memoir, Wilkins discussed his own lapses with alcohol and extramarital affairs. He said “nobody would have believed my messages if I had presented myself as a pristine and innocent victim of all those bad white folks.”

Wilkins was born in 1932 in Kansas City, Mo., where he was forced to attend segregated schools. His father was a journalist and his mother was national leader in the YWCA.

After his father’s death when he was 8, his family moved to New York City and, later, Grand Rapids, Mich. He earned bachelor’s and law degrees from the University of Michigan.

In a 1969 New York Times profile of his famous uncle, Wilkins said that once when he was fresh out of law school, a member of a prominent law firm asked his uncle if he should be hired.

The elder Wilkins responded, “Well, how do you usually judge people you are going to hire? Judge Roger the same way, hire him or not, as you would anyone else.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.