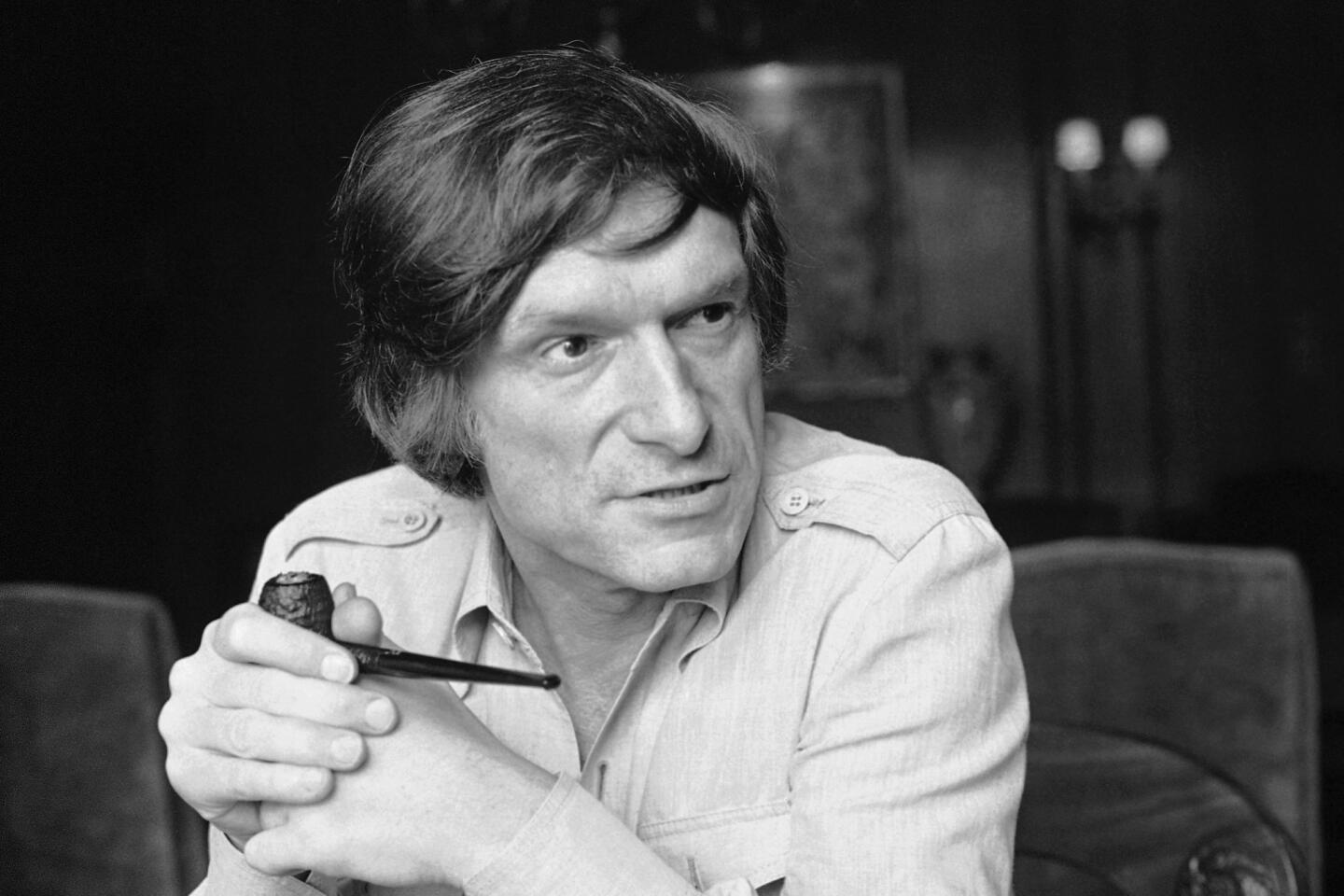

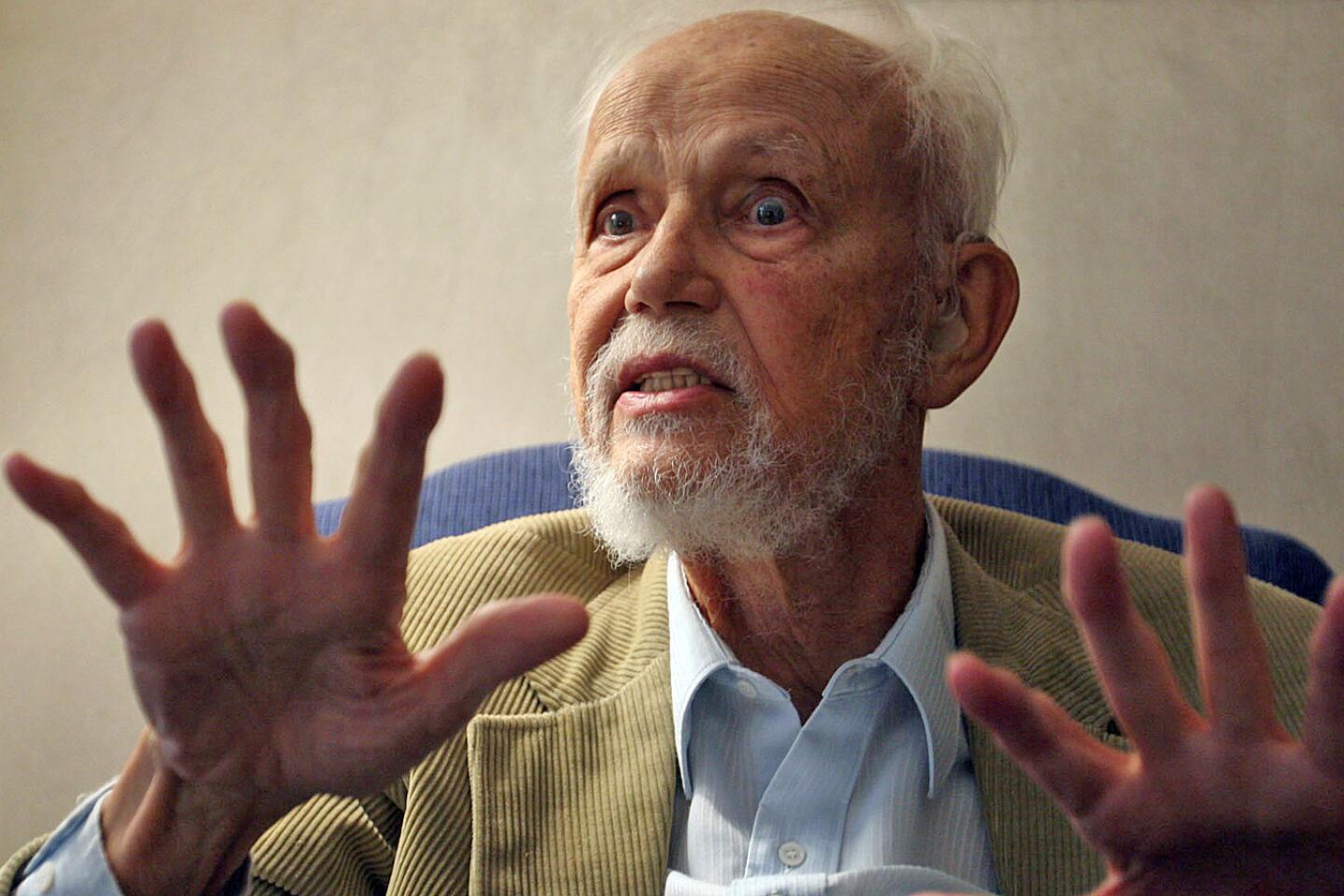

The slapstick, the telethons, ‘L-a-a-a-dy!’ — comic and philanthropist Jerry Lewis dies at 91

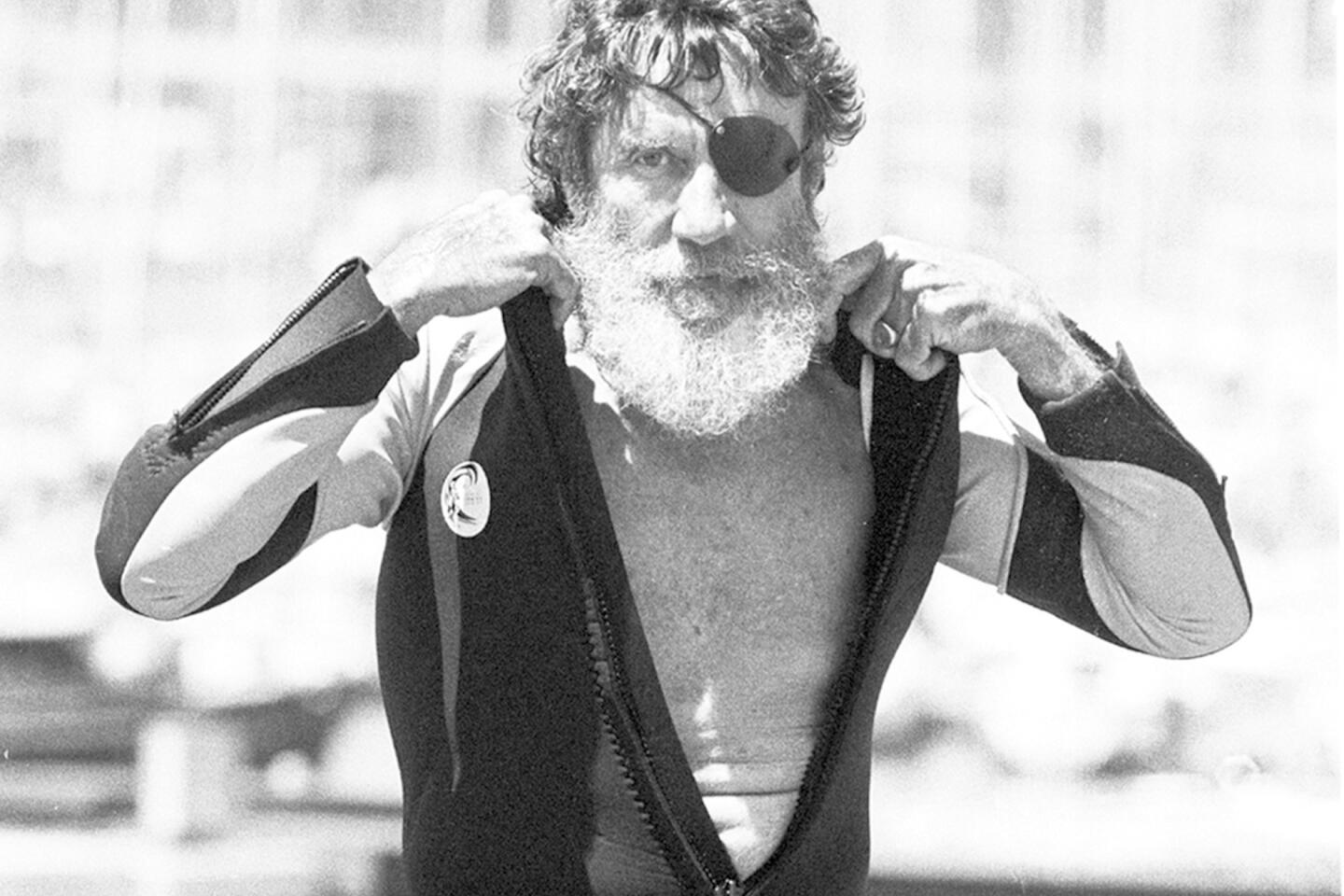

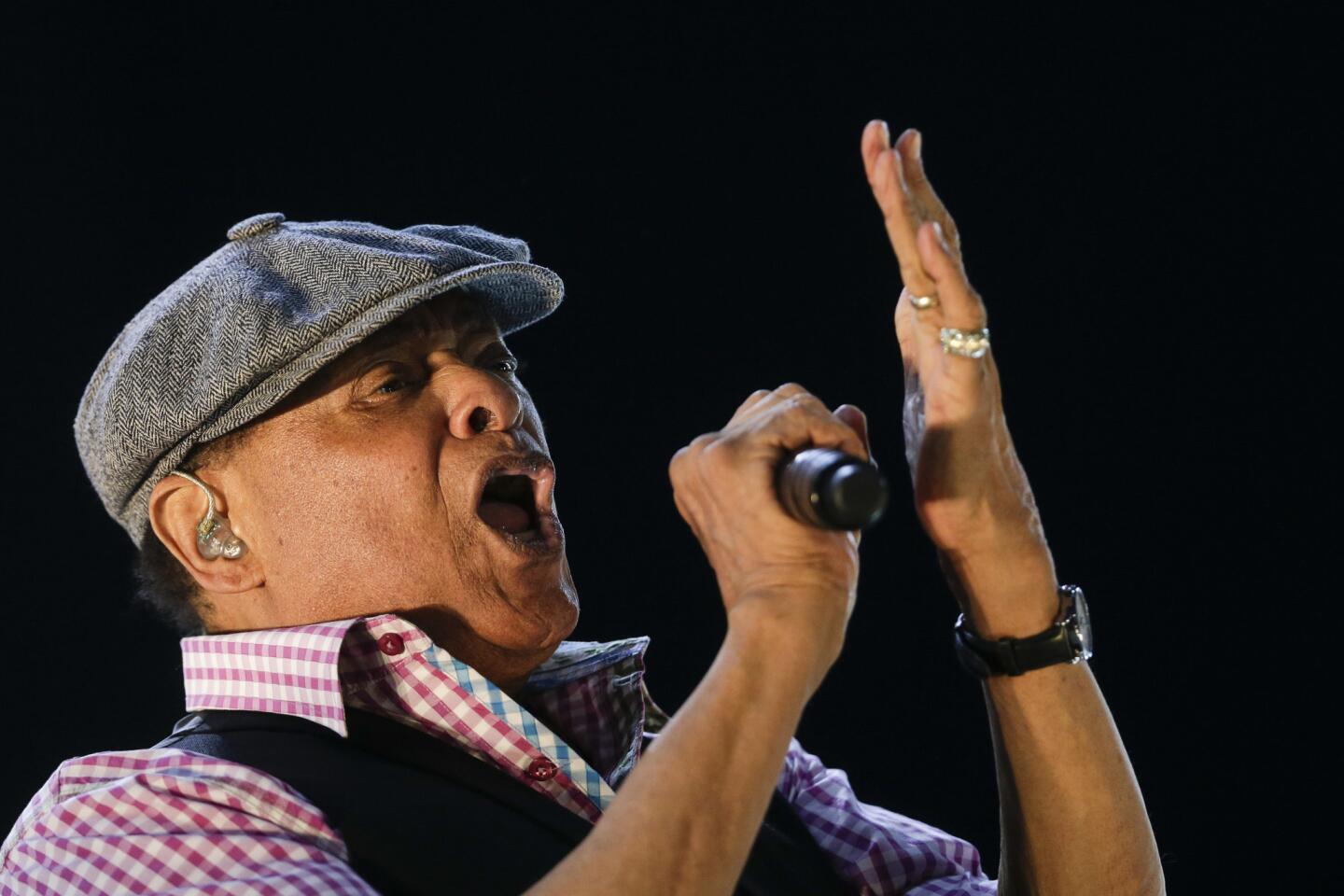

For decades, Jerry Lewis’ star had been as bright as any comedic force in America. His partnership with Dean Martin forged the hottest comedy team of an era, and his films were embraced by audiences raised on his manic, over-the-top, rubber-faced routines.

Then, as if by design, he shifted gears and poured his energy and time into philanthropy as host of the annual Muscular Dystrophy Assn. telethon, a charity event he hosted for 44 years. As he raised hundreds of millions, however, his own work as an actor and filmmaker became eclipsed, sliding into the distance.

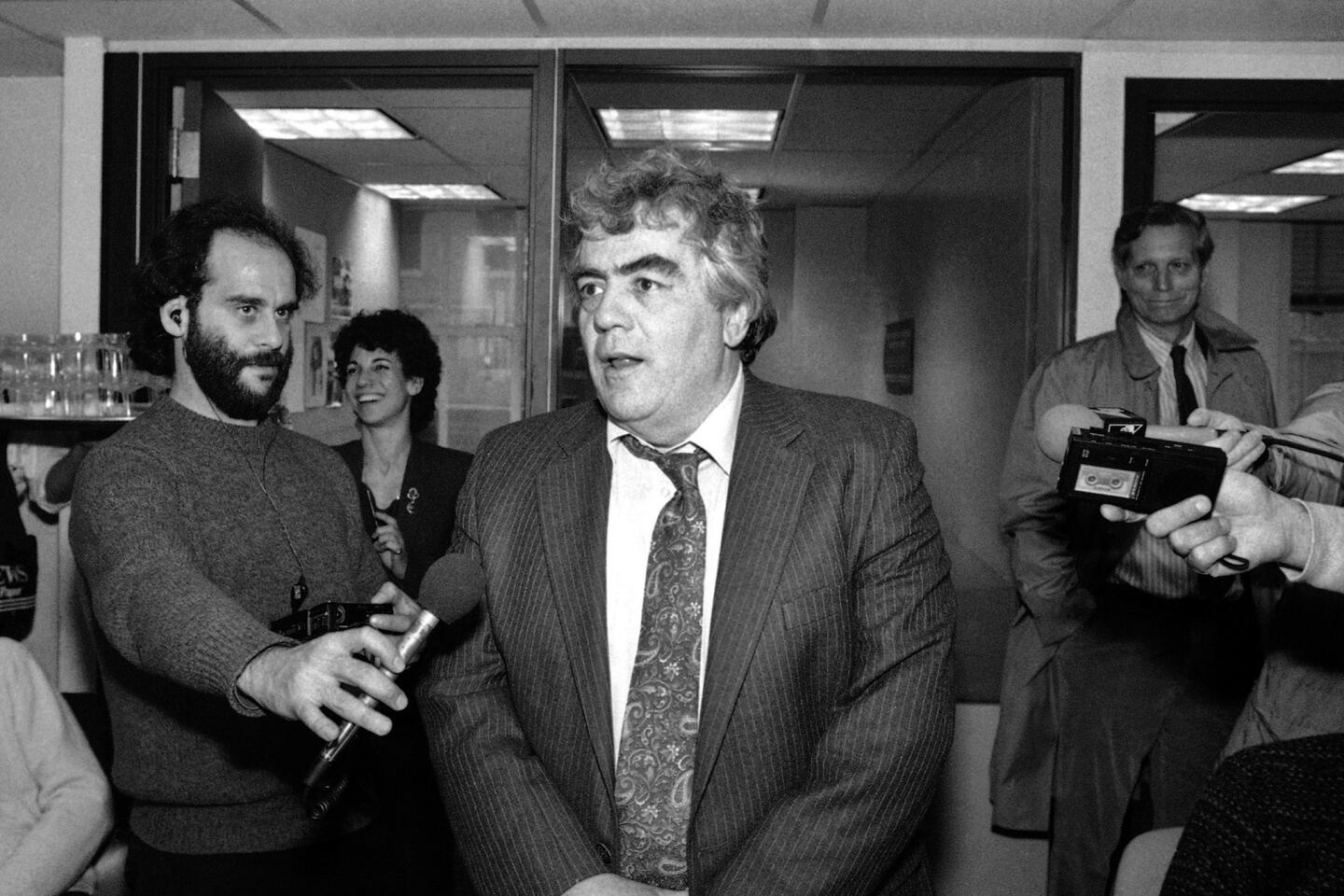

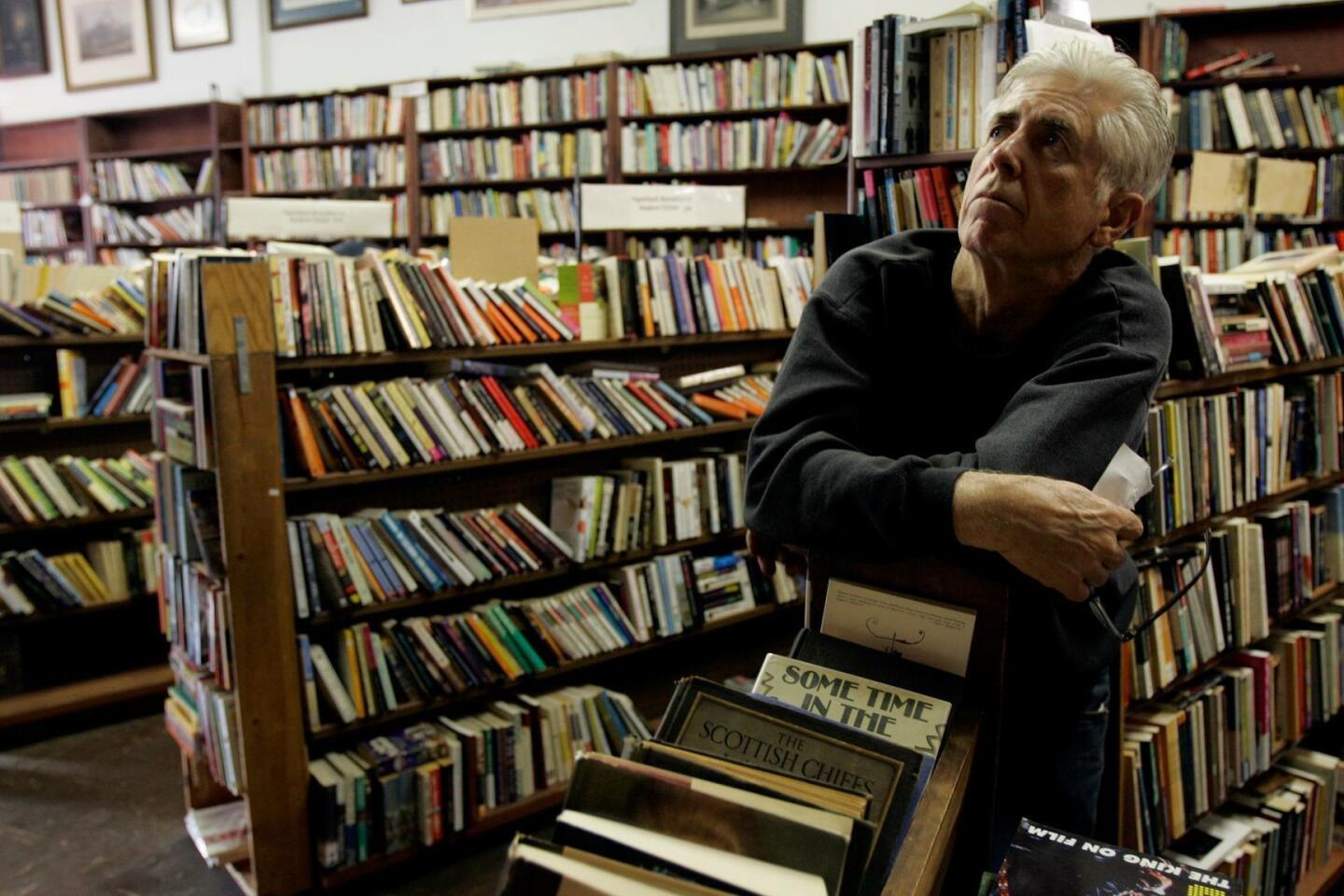

But in a dramatic and unexpected return to cinema in Martin Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy” in 1982, Lewis reignited the admiration of longtime fans and introduced himself to a whole new generation of movie lovers.

Lewis died Sunday morning of natural causes in Las Vegas with his family by his side, his publicist Candi Cazau said. He was 91.

In a show-business career that spanned more than 70 years, Lewis at various times was said to be the highest-paid nightclub comic, television entertainer and film director in the world.

“He was the top comedy star of his generation,” the film critic and historian Leonard Maltin said Sunday. “First in tandem with his partner Dean Martin and then on his own in the mid-1950s.”

And with Martin for 10 of those years, he was half of what has been called the most successful comedy duo in history.

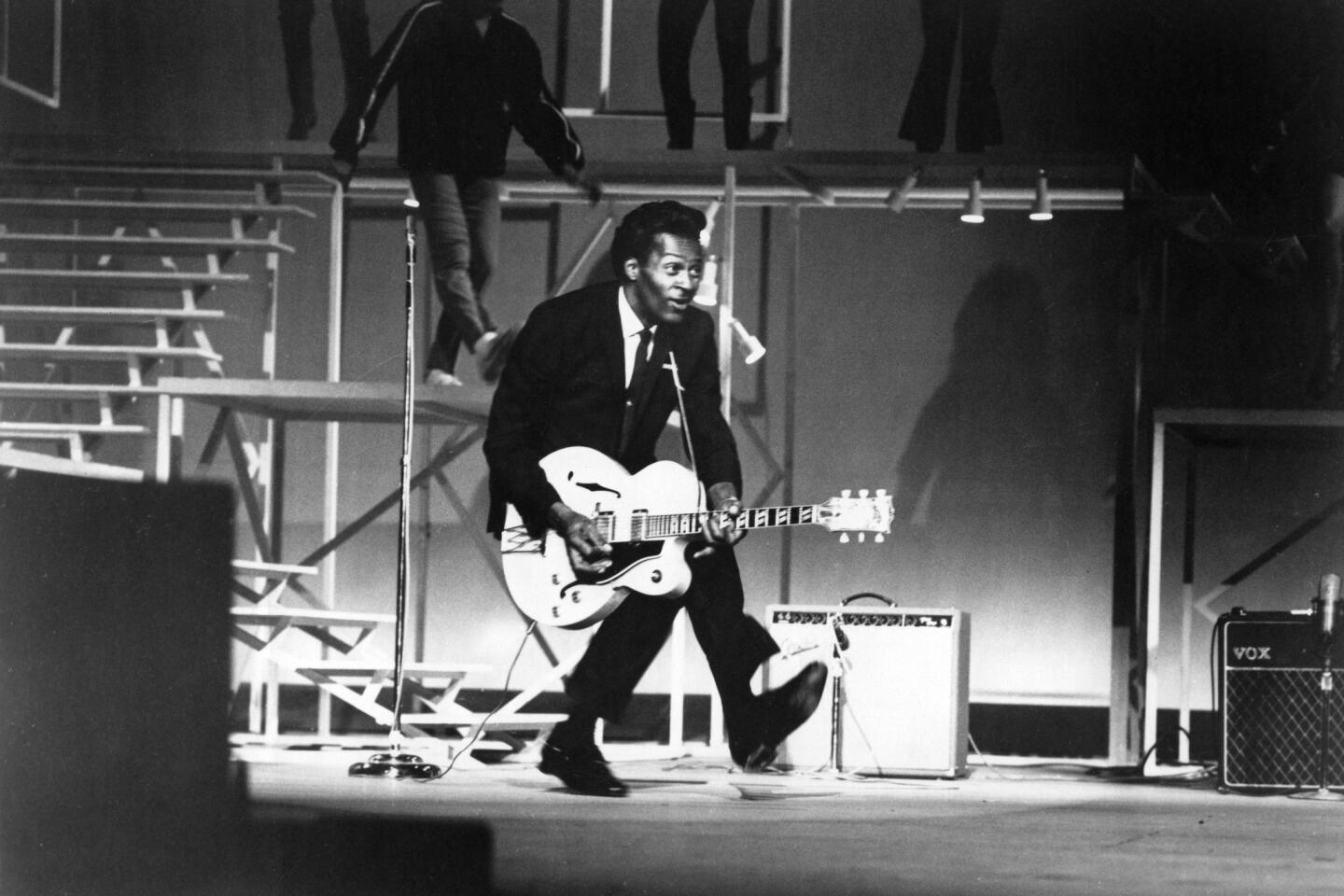

They teamed on stage for the first time in 1946, in a boardwalk nightclub in Atlantic City, N.J. Audiences had never seen anything like them: Martin, the handsome Italian crooner with the laid-back style; Lewis, the skinny, animated “kid” with the shrill, adolescent whine.

On stage together, Martin and Lewis were known as a super-charged mix of jokes, routines, singing, dancing and, most notably, ad-libbing. The wildly unpredictable Lewis thought nothing of cutting off customers’ neckties, flinging food off their plates or setting the musicians’ sheet music on fire.

“I have been in the business 55 years, and I have never to this day seen an act get more laughs than Martin and Lewis,” comedian Alan King once recalled in the New Yorker, decades after seeing the team perform at New York City’s fabled Copacabana nightclub in 1948. “They didn’t get laughs — it was pandemonium.”

Martin and Lewis created pandemonium off stage as well, generating the kind of frenzied mob scene previously reserved for the likes of bobby-soxer heartthrob Frank Sinatra and unheard of for a comedy act.

At the Paramount Theatre in Manhattan in 1951, Martin and Lewis performed six sold-out shows a day (seven on Saturday) for two weeks. With lines forming outside the theater as early as 6 a.m., more than 22,000 people a day flocked to see them.

On television from 1950 to 1955, the comedy duo regularly hosted “The Colgate Comedy Hour.” And Lewis’ signature lines became national catch phrases, including “I like it! I like it!” and “La-a-a-dy!”

Excluding uncredited cameos in Bob Hope and Bing Crosby’s “Road to Bali,” Martin and Lewis appeared in 16 feature films together — from “My Friend Irma” in 1949 to “Hollywood or Bust” in 1956. In 1952, they landed in first place in the annual Motion Picture Herald listing of the top 10 movie stars.

Lewis continued to score at the box office after going solo, beginning with “The Delicate Delinquent” in 1957. Two years later, he signed a record-breaking contract with Paramount Pictures: $10 million to appear in 14 films over seven years.

Lewis, who had made a point of learning about every phase of filmmaking from camera lenses to editing, went on to star in, direct and co-write a string of his own films.

“He had complete autonomy over his movies,” Maltin said. “He was such a big box office star that Paramount gave him carte blanche and he delivered the goods for them. He was also a great student of comedy who befriended Stan Laurel of Laurel and Hardy, and got to spend time with Charlie Chaplin, so he knew comedy inside out.”

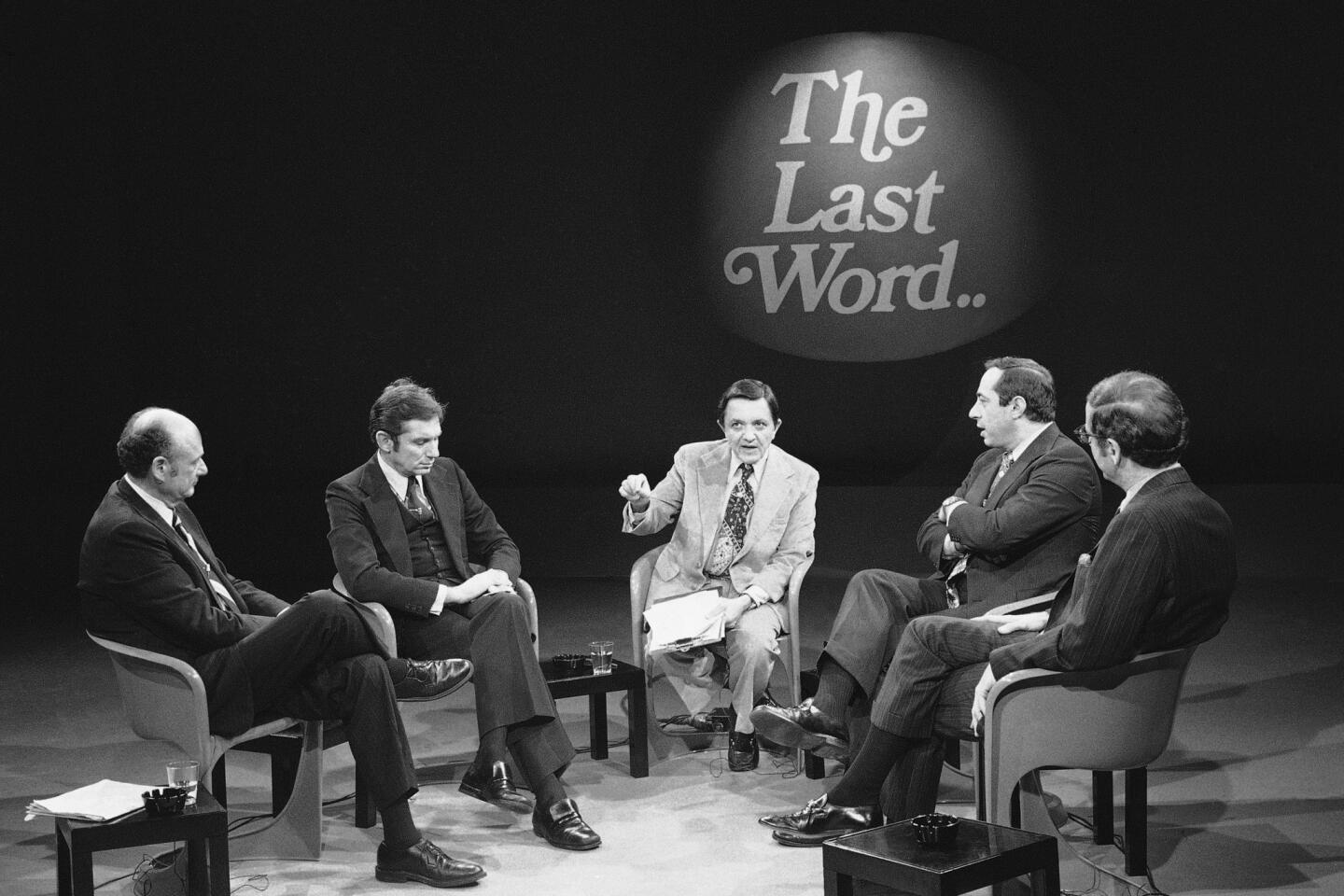

In late 1962, he signed a lucrative deal with ABC to host a weekly, two-hour, live Saturday night variety-talk show.

Despite great fanfare from ABC, “The Jerry Lewis Show” was a legendary flop, canceled by the network after only 13 weeks in 1963. Lewis then took out full-page ads in the show-business trade papers that said simply: “Oops!!! jerry lewis.”

It was a rare public acknowledgment of failure from a star whom many considered to have one of the biggest egos in Hollywood, a man who in later years was given to referring to himself in the third person and calling himself “an American icon.”

“I don’t give a … if people think I have a fantastic ego,” Lewis told the New Yorker in 2000. “I earned it! I worked my heart out! And you know what? I’m as good as they get.”

Born in Newark, N.J., on March 16, 1926, Lewis was the only child of Danny and Rae Levitch. Danny was a small-time song and dance man; Rae was a pianist who went on the road with her husband while their young son stayed with relatives.

Lewis made his stage debut at age 6 during the summer of 1932, singing the Depression-era anthem “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” at a Jewish resort hotel, with his mother accompanying him on the piano.

By the time he was 12, he was demonstrating his ability to make people laugh: While working as a “tea boy” at a resort hotel in Lakewood, N.J., where his father was performing for the winter, Lewis and two waiters would do hilarious parodies of current movies for the guests in the hotel lobby.

A class clown with a gift for mugging, Lewis was expelled from high school at 15, then dropped out of a vocational high school 10 days before his 16th birthday.

He then attempted to break into show business in New York City with a lip-synch act in which he mugged outlandishly to records by Betty Hutton, Frank Sinatra, Carmen Miranda and opera star Igor Gorin.

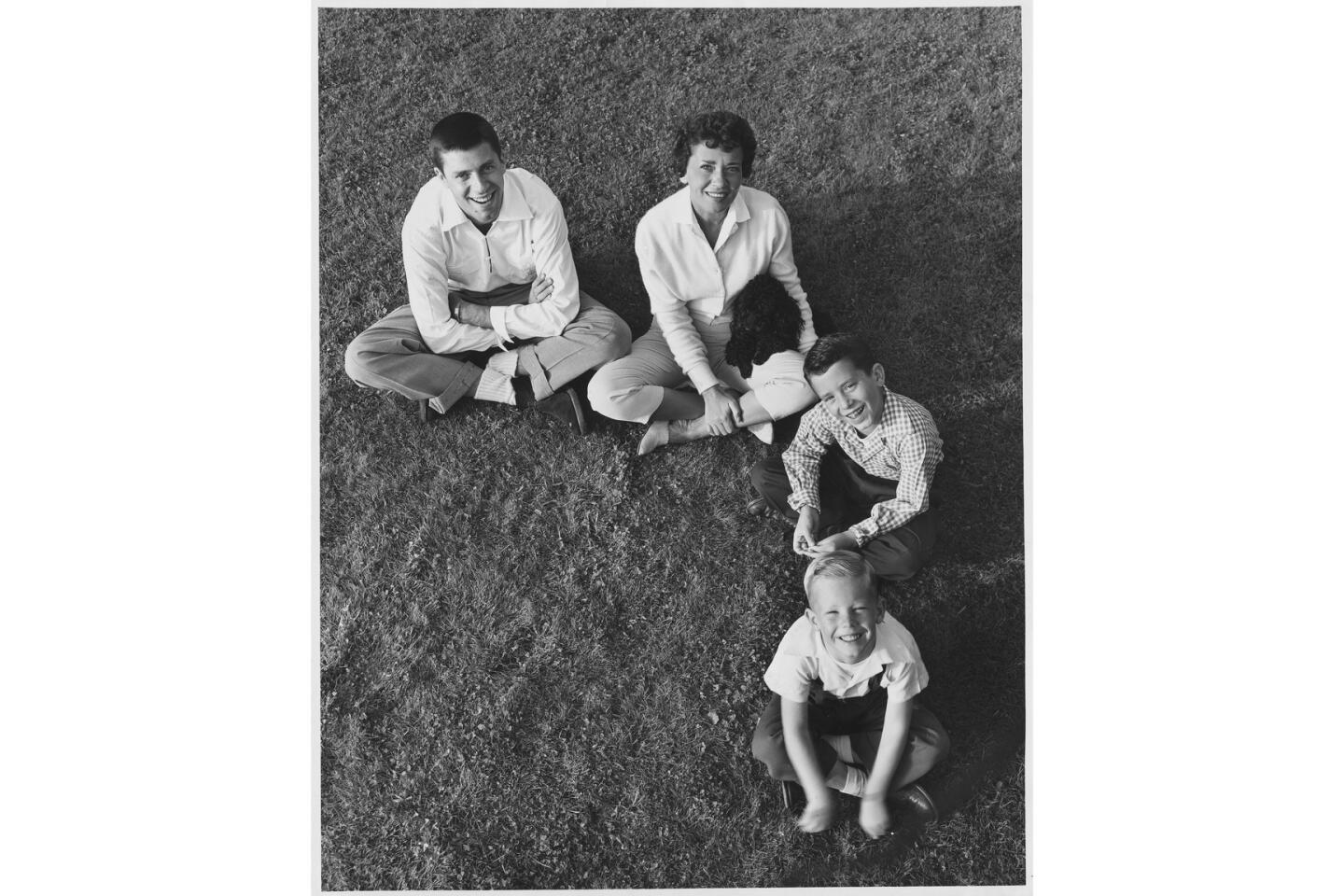

By the time he was booked into the 500 Club in Atlantic City in the summer of 1946, Lewis was 20 years old, still struggling to make his mark in show business with his record act, and the father of a year-old son. (He married Patti Palmer, a young singer with the Ted Fio Rito orchestra, in 1944; a perforated eardrum and a heart murmur kept him out of the military.)

When the singer on the bill at the 500 Club was fired, Lewis recommended a singer he had shared the bill with at the Havana-Madrid nightclub in New York several months earlier and with whom, he told the club manager, he had done “a lot of funny stuff” on stage: Dean Martin.

“A handsome man and a monkey,” as Lewis later described the heavily improvised act he and Martin performed at the 500 Club, was an immediate hit.

Lewis came out dressed in a busboy’s jacket while Martin sang. And from there, Lewis wrote in “Jerry Lewis in Person,” his 1982 autobiography: “We juggle and drop dishes and try a few handstands. I conduct the three-piece band with one of my shoes, burn their music, jump offstage, run round the tables, sit with the customers and spill things while Dean keeps singing.”

Within three nights of their July 25, 1946, debut, the new comedy team of Martin and Lewis was packing the 500 Club and crowds were being turned away even for the 4 a.m. show.

Two years after teaming up, Martin and Lewis were the hottest comedy act in show business.

From the start, Lewis received the lion’s share of attention from reviewers. Typically, a New York Times review of the team’s debut “Colgate Comedy Hour” appearance referred to Lewis as the team’s “works” while dismissing Martin simply as a “competent” straight man.

Lewis always maintained that no one really understood Martin’s “brilliance” as a straight man. In his autobiography, Lewis called his ex-partner “the greatest straight man in the history of show business.”

But as they continued making pictures and doing television and nightclub appearances, Martin finally grew tired of “playing a stooge,” tired of Lewis being singled out as the “crazy, funny” one, tired, in fact, of Lewis himself.

By the time they were working on their last film together, “Hollywood or Bust,” Martin reportedly told Lewis, “You’re nothing to me but a ... dollar sign.”

The Martin and Lewis roller-coaster ride ended on stage at the Copacabana in New York City on July 25, 1956 — the 10th anniversary of their first show.

Any fears Lewis had about going on his own were allayed two weeks later when he was asked to fill in for an ailing Judy Garland at the Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas.

With Garland, who had strep throat, sitting on the edge of the stage at Lewis’ request — the audience had paid to see Garland, after all — he did 55 minutes of what he called “nonstop clowning.” He closed his show by asking Garland what song she sang as a finish, then he proceeded to bring down the house with the old Al Jolson hit “Rockabye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody.”

Lewis recorded the song three days later. Released by Decca Records, it sold more than 1.4 million copies.

“The Bellboy,” a 1960 comedy written by Lewis and set in a Miami Beach hotel, marked his feature film debut as a director. He went on to direct, co-write (with Bill Richmond) and star in films such as “The Ladies Man,” “The Errand Boy,” “The Nutty Professor,” “The Patsy,” “The Family Jewels” and others.

But as Lewis took on the role of what he called “the total filmmaker,” some American critics felt his self-directed efforts were no match for his previous movies and castigated him for self-indulgence.

“The difference in his films was obvious: they were ponderous where once they had been light and airy, pretentious where once they had been so unassuming,” Maltin, the historian, wrote in his book “The Great Movie Comedians.”

The problem, Maltin argued, was that “there was no longer anyone to veto an idea, so Jerry indulged his every whim, allowed Jerry the comedian to milk gags far beyond endurance, and discarded conventional notions of good taste, modesty, continuity and — oddly enough — humor.”

Though largely dismissed by American critics, Lewis was considered a cinematic genius in Europe, where he was named best foreign director eight times and was made a commander in the Order of Arts and Letters, France’s highest cultural honor.

Wrote Shawn Levy in his insightful and not-always flattering biography of Lewis, “King of Comedy”: “Though it’s sometimes hard to remember, if not believe, Jerry Lewis was the most profoundly creative comedian of his generation and arguably one of the two or three most influential comedians born anywhere in this century.”

As a filmmaker in the early ’60s, Levy noted, Lewis was known for experimenting in sound, editing, set decor, cinematography and plotting. He also created the “video assist,” the now-extensively used closed-circuit television system that allows a director to watch takes on a monitor.

As a comedian, Levy wrote, Lewis “single-handedly created a style of humor that was half anarchy, half excruciation. Even comics who never took a pratfall in their careers owe something to the self-deprecation Jerry introduced into American show business.”

Said Lewis: “I never allowed my character to be any older than 9 years old. You just keep that age as a center point to work from and the mischief comes. I put it in the body of an adult man and I’ve made it work.”

But by the mid-1960s, Lewis’ brand of physical comedy had fallen out of fashion, and “The Kid” or “The Idiot,” as he called his bumbling and naive screen character, was beginning not to wear well on a man entering middle age.

Although he continued to tour and play Vegas, only one Lewis movie was released in the ’70s, the 1970 comedy “Which Way to the Front?”

Lewis’ 1972 film “The Day the Clown Cried,” in which he played a German circus clown who is sent to a Nazi death camp and used by his captors to lead unsuspecting Jewish children into the gas chamber, became tied up in litigation and was never released.

“Can’t talk about it. I won’t,” Lewis told The Times last year on the eve of the release of “Max Rose,” his first starring role in more than two decades.

He returned to the big screen in “Hardly Working,” a comedy about an unemployed circus clown, which received a critical drubbing although it did well at the box office when it reached U.S. theaters in 1981.

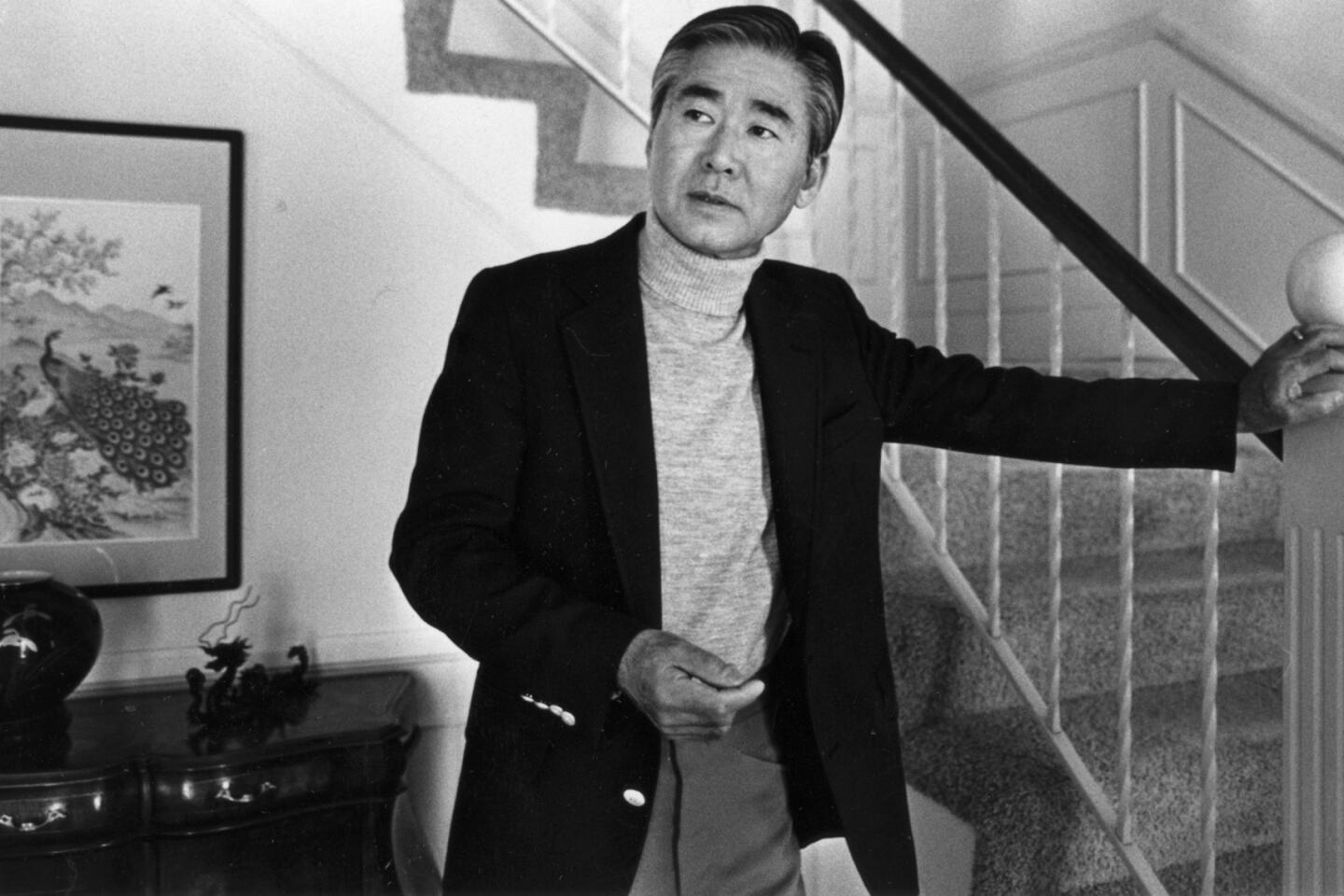

Then, in 1983, Lewis earned rave reviews from American critics for his first straight dramatic role: as a caustic comedian/talk-show host who is kidnapped by a fanatical fledgling comic (Robert De Niro) in Martin Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy.”

Despite the career triumph, the preceding years had been personally difficult ones for Lewis.

In the late 1970s, he revealed his dependence on Percodan, which had turned into a habit of 10 to 15 tablets a day.

In 1980, nearly 36 years after they eloped, Patti Lewis filed for divorce. Lewis admitted in several interviews that he had been unfaithful, particularly during the heyday of Martin and Lewis when, he said, “I was like a kid in the candy store.”

His personal problems continued a year later when his chain of Jerry Lewis movie theaters went bankrupt and he lost millions.

Even Lewis’ annual MDA telethon — a more than 20-hour mix of entertainers, testimonials and appeals for contributions concluding with Lewis typically fighting back tears as he sang “You’ll Never Walk Alone Again” — came under attack as a mawkishly sentimental pop-cultural institution whose “awfulness,” Washington Post critic Tom Shales wrote at the time, “is enshrined in tradition, like the ‘Miss America Pageant.’”

Over the past several decades, Lewis himself came under fire from former MDA poster children and others who claimed he portrayed them as objects of pity. In 1973, he was criticized for holding a child in his arms on the air and saying, “God goofed, and it’s up to us to correct his mistakes.

Still, from 1966 to 2010, the telethons raised more than $1 billion for what Lewis referred to as “my kids.”

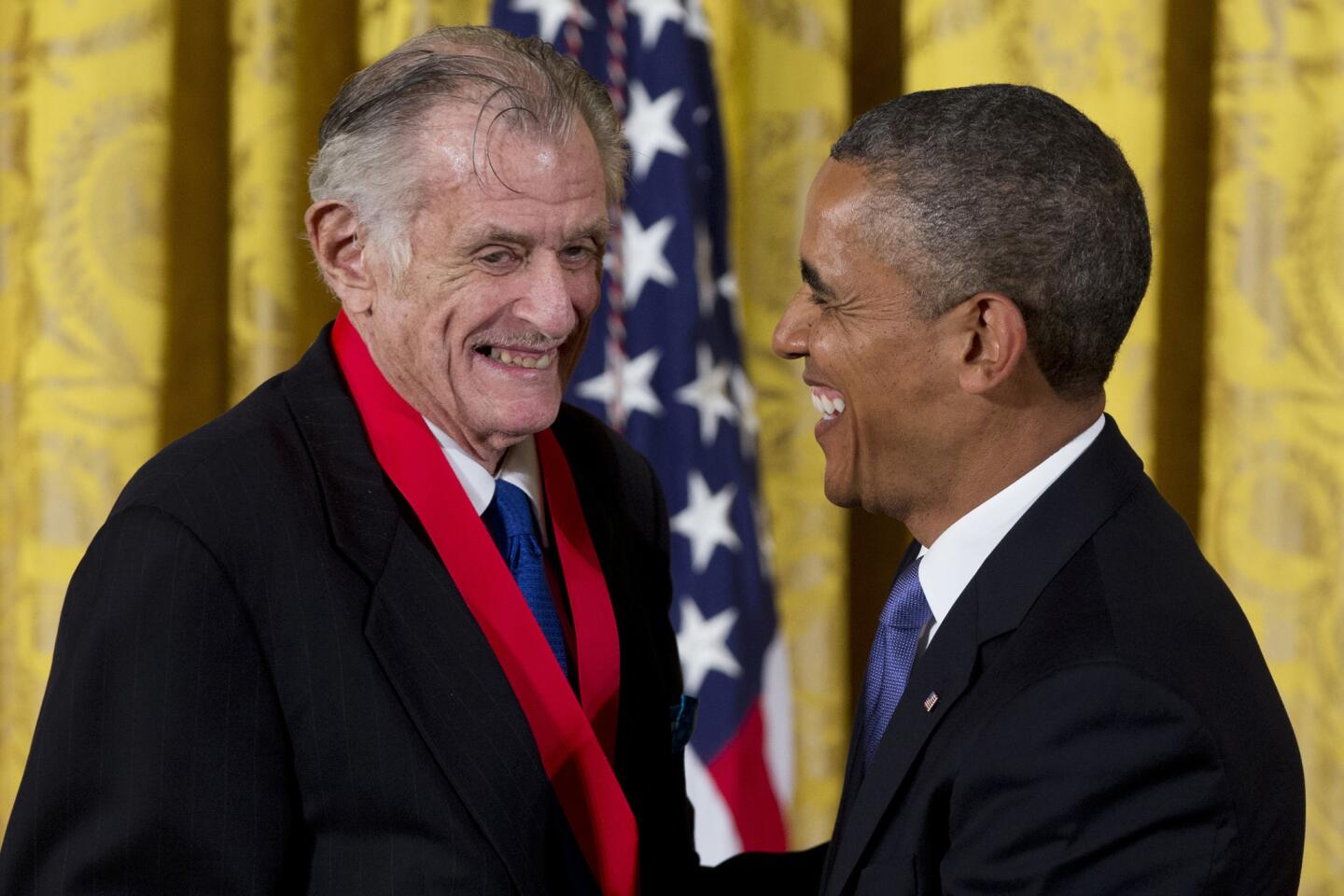

Lewis received the French Legion of Honor in 1984; a year later he received the U.S. Defense Department’s highest civilian award, the Medal for Distinguished Public Service. And at the Academy Awards ceremony in 2009, he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for his fundraising work on behalf of MDA.

In May 2011, Lewis announced that the upcoming Labor Day telethon would be his last as host. But that August, the MDA unexpectedly said the 85-year-old comedian would not appear as host on the telethon and would no longer serve as its national MDA chairman, a position he had held since the 1950s.

In 1983, Lewis married Sandra “SanDee” Pitnick, a divorced former stewardess and dancer whom he had cast in a bit part in “Hardly Working.” Nine years later, they adopted their newborn daughter, Danielle.

At the time, Lewis was nearly 69 and about to make his Broadway debut in a revival of the classic musical comedy “Damn Yankees.” He played the devil.

Lewis, who underwent double bypass surgery in 1982, suffered various ailments in his later years, including pulmonary fibrosis, an increase of fibrous tissue on the lungs. Among the drugs prescribed to repair his lungs was prednisone, a powerful steroid, which led to a more than 60-pound weight gain that left his face severely bloated.

The comedian also had been plagued by chronic pain resulting from an on-stage pratfall that chipped a portion of his spine in 1965. The injury led to a highly publicized addiction to the painkiller Percodan in the 1970s. In early 2002, the pain grew so bad that, Lewis later said, “I really thought about what gun I was going to use.”

But in 2002, he underwent surgery to have a device implanted that prevents nerves in the spinal cord from relaying pain messages to the brain.

For the first time in decades, the man who had taken pratfalls onto wood and concrete floors reportedly was pain-free.

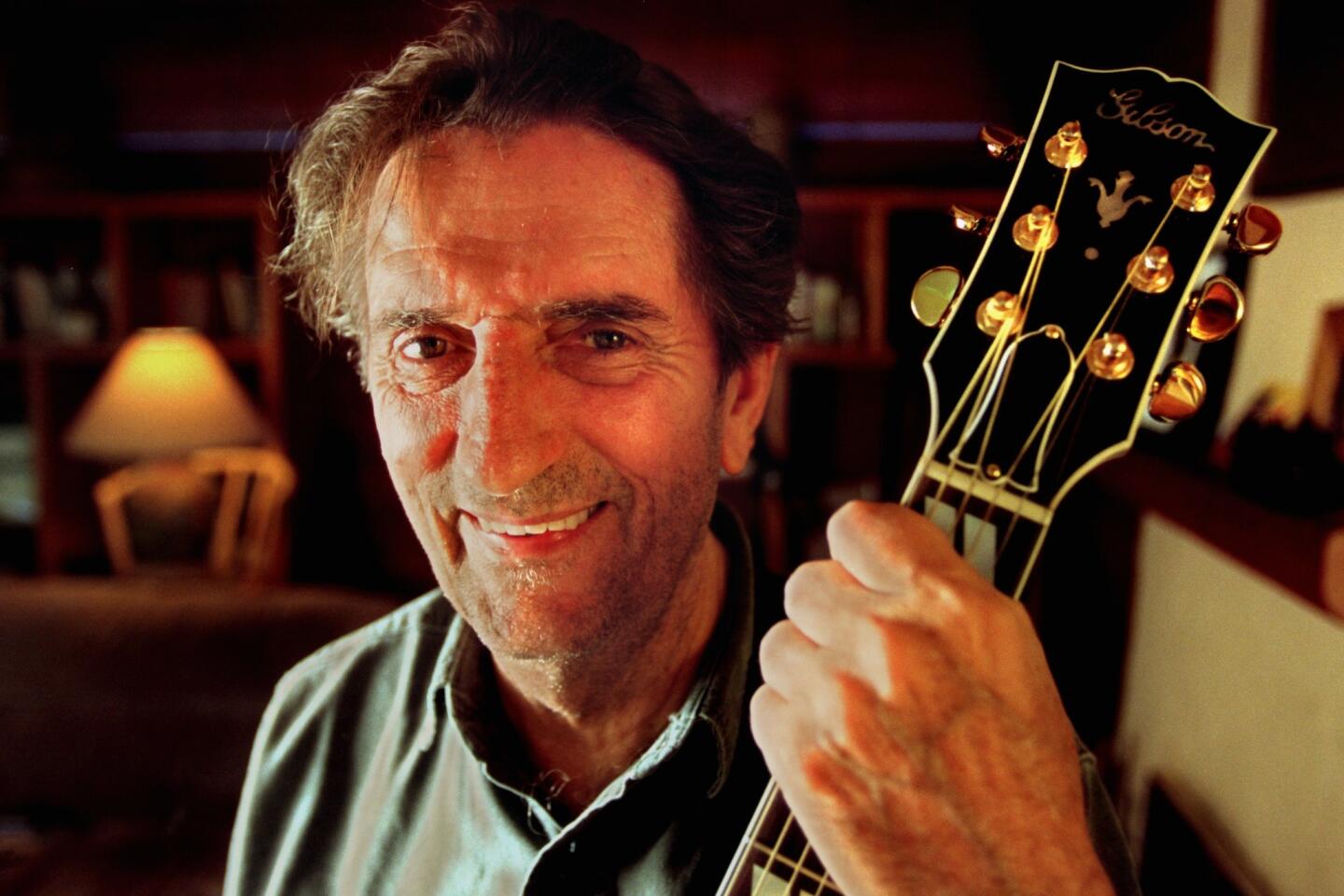

In the 2013 drama “Max Rose,” Jerry Lewis played a retired jazz musician who, while mourning the death of his wife, becomes suspicious that she carried on a long-term affair with another man.

In recent years, American film critics began giving Lewis belated appreciation for his movies.

In 2004, Lewis released wide-screen DVD transfers of 10 of his movies from his “total filmmaker” period, prompting New York Times critic Dave Kehr to write: “Is it finally time to stop with the French-love-him jokes and acknowledge that Jerry Lewis is one of the great American filmmakers?”

That same year, the Library of Congress added “The Nutty Professor” to the National Film Registry, acknowledging that it was a movie of lasting cultural significance and worthy of preservation.

And in 2005, the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn. presented Lewis with a career achievement award.

“Thank you very much, ladies and gentlemen,” Lewis said from the podium. “I am delighted to be the recipient of this award. What took so goddamned long?”

In 2012, the 86-year-old Lewis added something new to his extensive show-business resume: directing a stage-musical adaptation of his classic 1963 movie comedy “The Nutty Professor,” with a score by the late Marvin Hamlisch and a book and lyrics by Rupert Holmes.

The show, whose backers hoped to bring it to Broadway, featured a mostly unknown cast.

Using a mobility scooter to get around the Tennessee Performing Arts Center in Nashville, Lewis told the New York Times, “I say to myself, ‘You’re just as scared as the rest of them. You’re just as uncertain as these kids. And you have to use that uncertainty to get through to them.’”

Lewis is survived by his wife, SanDee; daughter Danielle; and four sons, Christopher, Anthony, Gary and Scott.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

Times staff writers Mark Olsen and Sonaiya Kelley contributed to this report.

ALSO

Glen Campbell dies at 81; country-pop singer battled Alzheimer’s

UPDATES:

5 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details and a response from film critic-historian Leonard Maltin.

11:50 a.m.: This article was updated with details about Lewis’ death.

This story was originally published at 11:10 a.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.